[CB – Chubb Ltd] A Port in the Storm

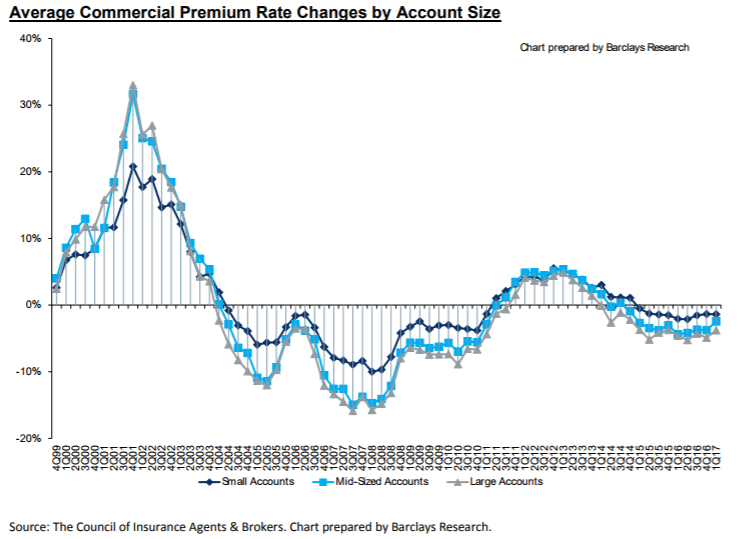

When referring to the insurance industry, folks often talk about “hard” and “soft” markets – periods of strengthening and weakening premium prices, respectively – as though they alternate with a high degree of regularity and are the predominant arbiter of premium growth. But this is untrue. 10 of the last 13 years and 22 of the last 31 have been characterized by declining rates. Over the last 46 years, just 3 “hard” markets – stagflation in 1976, the tort crisis of 1986, and the 9/11 tragedy – have fueled double-digit premium growth, all short-lived. Even momentous storm events like Andrew (1993) and Katrina/Rita/Wilma (2005) precipitated just a high-single digit bump in y/y industry premium growth. Of course, when you tune out the saliency bias stoked by media coverage of disastrous storm events, the transitory nature of rate inflation makes sense. The industry is characterized by fairly low entry barriers and marginal differentiation among a large number of operators, any one of whom stand poised to on-board recklessly priced risk at any given time. Instead, the real driver of net premium growth, what accounts for ~2/3 of it over time, is far more prosaic: nominal GDP.

Even as their pricing compresses, claims that insurers ultimately pay will keep inflating away. And then, on top of all this, the yields that they realize on their investment portfolios have declined from nearly 5% in 2002 to under 3% today, impairing an income stream that constitutes nearly all the profits of an industry that collectively underwrites to near break-even in most years. [An insurer derives income from two activities: underwriting and investing. Until claims actually have to be paid to insureds – which can be anywhere between 1-2 years for “short-tail” property risks or 10+ years for “long-tailed” liabilities like asbestos exposure – those premiums are invested in income-generating assets. So long as you underwrite to breakeven profitability, you are paying nothing to fund your investments…and if underwriting profits are positive, you’re essentially borrowing at “negative” rates (you’re getting paid) to invest. This is what Buffett means when he claims that “float”, while accounted for as a liability, is actually an asset for a underwriter who knows what he’s doing.]

I’ve read speculation that insured losses from Hurricanes Harvey and Irma could together approach $75bn. When combined with the $44bn in economic losses from disaster events in 1h17, 2017’s insured losses could approach $120bn, topping the $100bn of insured losses in 2005 (in 2016 dollars). It’s a meaningful dent to the industry’s $700bn of surplus, one that may prove the palliative to over dozen years of rate malaise. In any practice where luck plays a considerable role in outcomes (an inordinate one over short time horizons) and is often confused with skill, hucksters and dreamers flourish like bacteria to feast on the confusion. An insurer can recklessly underwrite risk and appear smart in a quiescent storm environment, just as a fund manager can look brilliant selling puts on broken companies in a raging bull market. We haven’t had a major hurricane in over a decade, providing cover for carriers who have under-priced new business for years…but this storm season could yank off the covers. One of my favorite Buffett pearls, pulled from the 1991 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter, applies well to the insurance industry, which fails “economic franchise” criteria (2) and (3).

“An economic franchise arises from a product or service that: (1) is needed or desired; (2) is thought by its customers to have no close substitute and; (3) is not subject to price regulation. The existence of all three conditions will be demonstrated by a company’s ability to regularly price its product or service aggressively and thereby to earn high rates of return on capital. Moreover, franchises can tolerate mis-management. Inept managers may diminish a franchise’s profitability, but they cannot inflict mortal damage. In contrast, “a business” earns exceptional profits only if it is the low-cost operator or if supply of its product or service is tight. Tightness in supply usually does not last long. With superior management, a company may maintain its status as a low-cost operator for a much longer time, but even then unceasingly faces the possibility of competitive attack. And a business, unlike a franchise, can be killed by poor management.”