[ODFL, SAIA, XPO] the LTL carriers are going to be ok

If I were to tell you about a company whose main job is to move freight from one place to another and whose primary assets consist of trucks and trailers, you’d probably think I was describing a capital intensive business with low entry barriers subject to brutal, commodified competition. And I could be! There is a massive $800bn industry made up of a million or so carriers who pack each of their 53-foot trailers with goods from a single shipper and drive it from a warehouse in, say, Boston to another in Chicago. The entry barriers are about as low as it gets. Anyone with a commercial driver’s license, a truck, and a tolerance for long road trips can do it.

But there is another sub-category of surface transportation, less-than-truckload, or LTL, that works quite differently. Whereas a truckload operator is tasked with driving a full trailer of goods from one point to another, an LTL carrier has the more complex job of combining smaller batches of freight from multiple shippers through a hub-and-spoke network, with each batch heading to different destinations. From my June ‘22 post [ODFL] Old Dominion and less-than-truckload:

In serving a just-in-time OEM that needs parts delivered at higher frequency in smaller batch sizes, a supplier might split cargo into 3 separate shipments, none large enough to occupy an entire 53-foot trailer, in which case they turn to a less-than-truckload (LTL) carrier that combines their freight with that of other shippers to fill up a trailer. What happens is the LTL employs pickup-and-delivery (P&D) drivers based at a local service center (aka, ”terminal”) in Boston and assigns each of them a dedicated territory (Cambridge, South Boston, etc.). Those drivers will drop off pallets in the morning, pick up pallets throughout the day, and deliver their collections to the Boston service center in the evening.

At the service center, dock workers combine our supplier’s pallet with pallets from other customers, loading the mixed, heterogeneous freight on trailers at one of the hundred or so loading-bay doors. A line haul driver takes this truckload to an intermediate hub in, say, Chicago, where shipments are once again stripped and re-consolidated with pallets brought in from various other terminals, and then hoisted onto a linehaul truck headed to the LTL’s service center in Los Angeles. From there, the supplier’s pallet is put on a P&D truck and delivered to the OEM’s facility in South LA (or whatever).

Getting this right requires a different set of assets and competencies. As I explained in my interview with Business Breakdowns:

So whereas a truckload operation can be as simple as a truck driver with a trailer full of goods from one shipper traveling from point A to B, an LTL operation has service centers where pallets of freight are aggregated; P&D drivers who pickup and the deliver freight in a local service area; dock employees at the service center who combine pallets; and linehaul drivers who transport freight from one service center to another. This is a capital intensive business with high fixed costs. LTLs need to acquire a fleet of tractors and trailers, they need to lease or, in Old Dominion’s case, outright own service centers, and then also bear the costs of driver and dock worker wages.

The key to scaling these fixed costs is density and efficiency. You want P&D drivers making as many pickups as possible along a given route. You want the right kind of freight, with pallets holding goods that are tightly packed together, with geometries that maximize trailer space so you’re not just moving air. You need dock workers who can unload and move pallets quickly without damaging freight. You need linehaul trailers maximally loaded with shipments. This is not the kind of thing that can be replicated all at once. It takes time to win credibility with shippers, to train dock workers to handle freight, and to build density in P&D routes and linehaul lanes. The barriers to entry are huge but so are the barriers to scale.

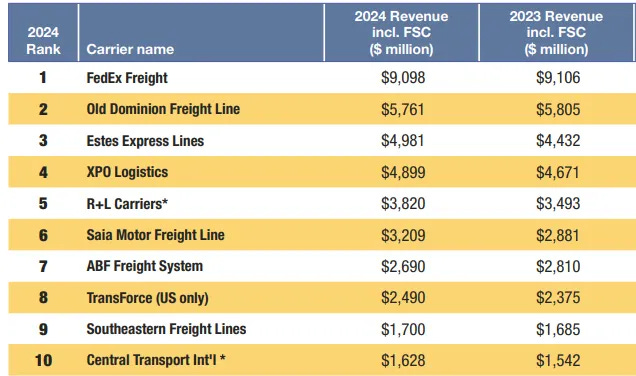

It comes as little surprise then that, relative to the hyper-fragmented Truckload industry, LTL is far more concentrated, with the top 10 US players comprising just over 3/4 of its ~$50bn of revenue:

Source: Logisticsmgmt.com; SJ Consulting Group, Inc

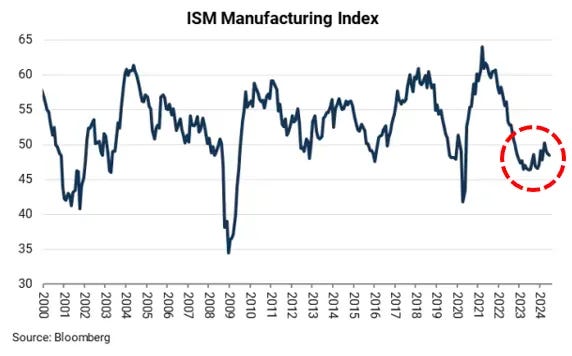

The last time I discussed the LTL industry was in November ‘22, at the tail end of an unusual boom for goods, fueled by companies over-stocking in response to supply chain disruptions and by stimulus-juiced consumers. The intervening three years have been unkind. The ISM Manufacturing Index – a kind of bellwether for an industry that gets ~two-thirds of its revenue from industrial freight – has slogged along below 50 (meaning, things are contracting) for 23 of the past 26 months. This brutal stretch has confounded everyone, as industrial downturns over the last few decades have tended to be brief and self-correcting. Old Dominion’s management team predicted a recovery in freight volumes back in 4q22. Volumes continue to decline three years later. Inflation, destocking, tariffs, and a rotation from goods back to services have all, to varying degrees, been called out as culprits at different times.

In August ‘23, against this dolorous demand backdrop, Yellow, who had gasped on death’s threshold for more than a decade, finally filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. At the time it went under, Yellow was the third largest LTL, responsible for about 10% of industry volumes. The remaining carriers feasted on Yellow’s orphaned shipments, helping to paper over a weakening freight cycle….for a little while at least, before the nasty macro environment re-asserted itself.

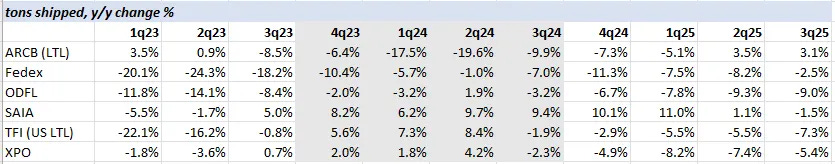

(ArcBest stands out from the pack in that its tonnage losses accelerated in the quarters following Yellow’s bankruptcy. In disaggregating the tonnage components, what you’ll find is that the number of LTL shipments held up reasonably well in 2024, but weight per shipment declined double-digits as it appears management re-priced and deliberately sacrificed transactional shipments, which tend to be heavier than shipments tied to contractual arrangements).

Most of Yellow’s 169 owned and 142 leased terminals were also picked off. By mid-2025, the Yellow estate had sold or transferred leases on 210 properties in transactions worth ~$2.4bn. The largest bidder, XPO, paid $918mn in auction for 28 of Yellow’s properties (26 owned + 2 leases). Estes Express, after failing to acquire the entire portfolio for $1.5bn, settled for 52 terminals, paying $490mn. Old Dominion also tried to buy all of Yellow’s service centers on the cheap, but after being outbid it ultimately didn’t buy any. SAIA spent $244mn on 28 terminals, R+L shelled out $283mn for 13. The rest were parceled out in piecemeal fashion until, by April ‘25, Old Dominion’s management estimated that ~60% of Yellow’s pre-bankruptcy facilities were “reallocated or repurposed”.