[MELI – MercadoLibre] Digging the Moat (Or Is It A Grave?), Part 2

In nascent markets with winner-take-most dynamics, it’s particularly hard to know in the moment whether or not a company’s investments will ultimately add shareholder value. You’ll know when you get there but getting there means engaging in what looks like and very well may be, a reckless race to the bottom. But, to abstain while competitors spend gobs of money on marketing, logistics, and other formative flywheel catalyzing elements? Well, you may as well not even play. So then what often happens is we wait for the outcomes and reverse engineer explanations for why this company succeeded and that company, which also cared deeply about nurturing and investing in terrific consumer experiences, failed. Once notable entities like Webvan and Pets.com are tsk-tsked as cautionary tales of profligate spending while Amazon is widely worshiped as long-term greedy. We can point to attractive unit economics after the fact, but the path to profitability is usually not plainly obvious in the moment.

I bring this up because in response to an increasingly competitive landscape in Brazil, Mercadolibre has been ramping shipping subsidies, to the great detriment of near-term profitability and uncertain impact on long-term value. A year ago, free shipping was launched as a pilot in Mexico and accounted for less than 2% of MELI’s revenue; today, over 60% of Libre’s GMV in Brazil, nearly 80% in Mexico, close to half in Colombia is covered by free shipping, whose costs consume 25% of total revenue. On top of that, earlier this year Brazil’s national postal carrier, Correios, hiked its shipping rates, directly eating into MELI’s margins for most of the quarter. Those twin uglies have hammered profitability…

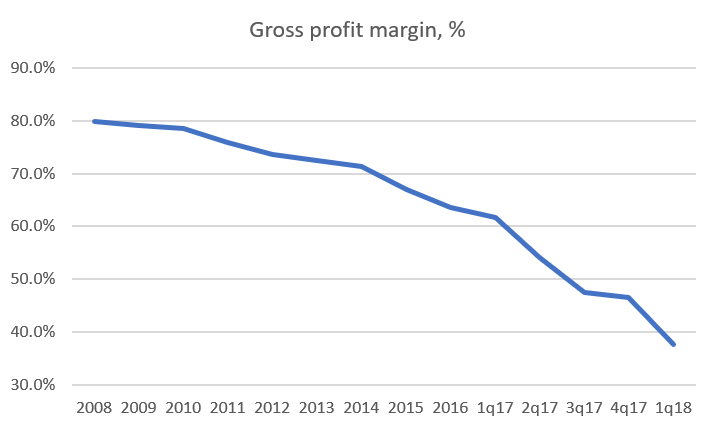

[shipping freebies have historically been included in cost of sales, but were accounted for as contra-revenue starting 1q18, so gross revenue minus shipping costs paid for by Mercadolibre = net revenue. To make current gross margins comparable to historical ones, I added shipping costs back net revenue in the denominator] Gross margins were in persistent decline even before shipping subsidies were introduced in earnest in 2017, but pre-subsidy margin contraction can mostly be attributed to growing adoption of Envios and Pago, the company’s integrated payments and shipping solutions, respectively, which carry lower margins but nonetheless play important, structural roles in sustaining MELI’s marketplace flywheel.

[Clayton Christensen has pointed out that in immature markets, product performance is often best optimized by tightly integrated architectures. As product performance becomes “good enough” to meet customer needs, other concerns, like customization and speed to market, take on more significance, and the integrated stack dissolves to a more modular set up, made up of independent pieces that interact with each other in predictable ways. Clayton was writing about this point in the context of the computing industry – for instance, from mainframes (chips, hardware, operating system, and applications all tightly integrated) to Wintel (hardware and chips modularized, OS/application integrated) – but the principle applies here as well. Latin American e-commerce is at such an early stage, the surrounding financial/logistics infrastructure so immature, that an integrated approach to the market is required.]

Brazil, which accounts for 60% of marketplace net revenue and was Mercadolibre’s most profitable market, has seen its profits plummet. The region barely operated at break-even last quarter:

And what are the competitive challenges inducing such an aggressive posture?

Late 2017 brought news that Amazon, which had mostly sold books and media in previous 6 years since it entered Brazil, would start carrying electronics on its marketplace. That announcement whacked shares of MercadoLibre and domestic e-commerce peers like B2W, Lojas Americanas, Via Varejo, and Magazine Luiza. Then earlier this year, Amazon was reported to have been looking to lease a 500k+ square foot warehouse outside Sao Paulo, signaling an interest in assuming more control of its logistics operations, which up to then had been outsourced to third parties.

But as formidable a foe as Amazon has proven itself to be, the company begins its expansionary gambit as an underdog in Brazil. E-commerce marketplaces are local phenomena and scale advantages do not necessarily cross borders. Amazon is effectively building a presence – infrastructure, suppliers <-> shoppers, maybe payments – from scratch. Entering a new geography is more challenging than breaching a new product category (like, say, dog food) within an existing geography, where infrastructure and customer loyalty can be leveraged. In February 2018 47% of consumers in Latin America made online purchases on MercadoLibre vs.17% for Amazon, and we know that Brazil is by far the largest e-commerce market in Latin America, so perhaps we can draw an inference for relative popularity in Brazil?

Perhaps the more pertinent challenge to Mercadolibre’s success in Brazil are domestic incumbents with brick & mortar roots who are leveraging their store footprints and their networks of distribution centers and 3rd party transportation providers, to break into e-commerce:

Here is Goldman’s estimate of Brazilian e-commerce market share among the top 3 players, from 2015: B2W: 23% Cnova Brazil (now owned by Via Varejo): 16% MercadoLibre: 15% I am a bit baffled by Goldman’s figures. In 2015, B2W’s total GMV in US dollars was around $3bn, while MercadoLibre’s total GMV, across all its regions, was over $7bn. While MELI doesn’t disclose GMV by country, we do know that its marketplace revenue in Brazil accounted for 40% of the total, implying perhaps $2.5bn-$3bn in GMV in Brazil assuming comparable take rates across regions. So, it seems to me that B2W and MercadoLibre had roughly comparable marketshare in 2015. And since then, Libre Brazil’s GMV has been growing its face off, expanding by 50%-60%+/year in local currency terms, many times faster than B2W and Brazilian e-commerce as a whole. Magazine Luiza, too, has been taking share, growing just as fast as MELI and sustaining margins to boot. Cnova Brazil’s growth, on the other hand, has languished.

[Note: B2W claims that its e-commerce market share in 2017 was 28%, which breaks my math as the numbers in the above table sum to more than the implied $13bn TAM. But this TAM (or B2W’s reported share) seems a bit suspect to me. B2W’s GMV grew by 11% in 2016 and 3% in 2017 in an e-commerce market that by most accounts I’ve seen grew by teens, and yet B2W claims to have gained 2 points of market share during this time? Hmm. Brazil e-commerce market size estimates vary, from $14.5bn (PagBrasil, export.gov) to ~$20bn+ (PFS, Statista). Whatever the case, e-commerce is a low-single digit share of retail in Brazil, so there’s still tons of expansion opportunity ahead. Still, if you have a different/better take on $TAM or market share, please email me, I’m curious.]

MercadoLibre prides itself on being the only e-commerce player in Brazil to offer a “full stack” marketplace that embeds payments and logistics. MercadoLibre’s in-house shipping service, MercadoEnvios (“Envios”, launched in 2013/2014) is a huge improvement from its prior state of affairs, when buyers had to arrange shipping directly with merchants, leading to wildly inconsistent pricing and delivery times. Today, 2/3 of items are shipped through Envios compared to less than half just 2 years ago.

But while MercadoLibre may own the coordinating technology that matches customer orders to shippers, it does not control its own logistics network. Fulfillment centers and warehouses are instead operated by local operators, who run logistics for many other clients besides MELI [most of MercadoLibre’s orders are drop-shipped, meaning third party shippers pick up the ordered goods from merchant warehouses and deliver those goods to customers]. By outsourcing logistics, a marketplace reduces upfront capital investment and other fixed costs…but because shipping times are a critical part of the customer experience and because no third party will care about satisfying your customers as much as you, the capital efficiency benefits of relying on third parties may be more than offset by lower customer lifetime values.

Consider the disparate reviews that Amazon has seen in markets where it owns vs. outsources logistics.