[V – Visa; MA – Mastercard] Expanding the Rails, Part 1

The basic moatiness of V/MA has been tirelessly discussed for years and is well understood, so I’ll try not to belabor the point and focus instead on some less frequently explored angles. But I do need to establish a common denominator, starting with the 4-party model….apologies if you know all this, I’ll be quick about it.

4 parties: issuer (the bank that issues the credit or debit card and bears the credit risk), cardholder (you and me), merchants (grocers, retailers both online and offline), acquirer (the merchant’s bank, who may also be a card issuer, and less well known companies like First Data, Heartland Payment Systems/Global Payments, Vantiv).

When you swipe your credit or debit card, the merchant receives the price of the good minus a fee – calculated as the “merchant discount rate” (which varies widely by merchant, country, and transaction size) times the value of the good – from the acquiring bank. So, for instance, on a $100 credit card transaction, a 2% merchant discount rate results in the merchant receiving $98, with most of the remaining $2 kept by the issuer (“interchange fee” set by the credit card companies), who bears the credit risk. Other constituents, namely the merchant acquirer and payment processors on both the merchant and issuer side, get a (much, much smaller) piece of the MDR action too. The card networks, who act as the middlemen, the tollbooths, the payment rails…pick your analogy, route transactions to the issuer for approval, securely facilitate the exchange of information and payments between parties, and receive fees from issuers and merchant acquirers on each transaction. While these fees are a tiny ~13c per $100 transaction, they accumulate to big dollars when multiplied across $11 trillion in MA + V global payment volumes.

Visa has about 3bn cards outstanding, issued by 13k issuers and accepted by 44mn merchants. Its network (VisaNet) supports around $7tn in global payments volume….that’s ~100bn transactions/year (peak volume of 17k messages/second) across 160 currencies in 200 countries (Mastercard has 1.7bn cards outstanding and its network supports close to $4tn in global payments annually). If you wanted to build your own payments network to compete with Visa, you’d need to win over the issuing banks. Of course, you won’t get the issuers if you don’t have merchants to accept your card and you won’t get the merchants unless you have the issuers’ card customers, who want to know that the card is accepted nearly everywhere…and, critically, you won’t get anyone unless you can ensure security, which itself depends on the insights garnered from the 100bn+ of transactions these two networks process every year. Every time you swipe your card, Visa evaluates over 500 different data points to determine fraud risk, calculates a risk score, and sends that score to the issuer to approve the transaction….all in a fraction of a second. Clearly, this is a tough chicken/egg nut to crack.

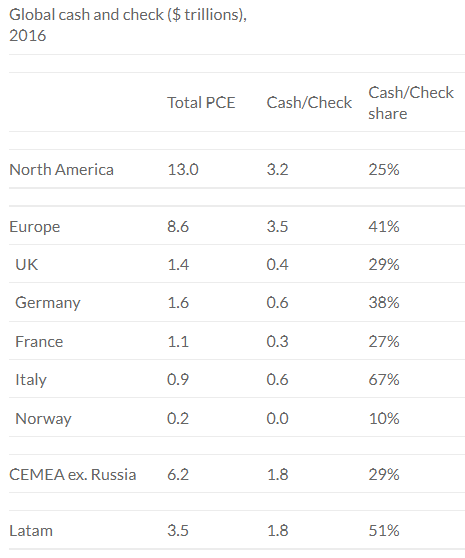

For at least the last decade, the primary bull case for V/MA has been the conversion of cash and check to electronic payments, and this remains true today, particularly with e- and m- commerce sales growing 5x faster than physical retail. In fact, even while card share of global payments has increased from 31% to 36% from 2012 to 2016, the absolute dollar value of cash and check transactions has actually increased by ~2%/year, from $15.6tn in 2012 to $17tn in 2016 vs. $7.1tn and $3.5tn of global payments volume at V and MA, respectively. If we strip out China and Russia, cash/check transactions are more like $14tn. At a high level, there’s about $43tn in global personal consumption expenditures (PCE). Stripping away China and Russia, we’re at $38tn. If the US is any guide, then 70%, or $27tn, of that is addressable (ex. government subsidized healthcare, insurance, rents, financial services).

The opportunity to convert cash volumes to electronic ones varies greatly by region [note: this table shows total PCE and includes non-discretionary spending categories that aren’t entirely relevant….the point is just to show the disparity between different geographies]:

The most salient region here is obviously APAC ex. China, where over 60% of spending is still mediated by cash/check and the absolute levels of cash/check are greater than any other region. [UnionPay operates its payment network in China as a monopoly. Visa and Mastercard are locked out of the domestic market for the time being, though they still handle cross-border transactions, which itself is a pretty big business with over 130mn Chinese citizens traveling abroad each year. Visa is pursuing a domestic license and putting feet on the ground so that it’s ready if/when the market opens up to outsiders. But, this will be a long process. Even assuming that China is receptive to foreign card networks, there’s about a dozen government agencies that have to serially approve the domestic license].

I mentioned in a previous post that payments is an inherently local market. Not only are these countries in various stages of economic development, but the transition from cash to electronic payments will evolve in different ways. There is no inherent reason why plastic cards must be the primary delivery mechanism. It turned out this way in the US because from the 1950s up until about a decade ago, when smartphones proliferated in earnest, this was the most convenient way for consumers to electronically transact…and specialized terminal equipment connected through phone cables arose to accommodate that medium at point-of-sale. In many emerging markets – where the cost and time required to purchase a credit card machine and connect it to a payments network has limited electronic payments adoption among a fragmented landscape of small, mom-and-pop vendors – smartphones not only arm citizens with payment devices (in some CEMEA countries, mobile penetration is > 150% among the adult population and well exceeds banking penetration) but goes a long way to removing merchant acceptance barriers. Under the traditional card/card machine setup, retailers can only pull funds from the customer’s account. With a smartphone, a customer can push funds to the merchant.

In India, where the government is aggressively promoting a cashless economy, Visa and Mastercard have worked with the government to create a QR standard (Bharat), with 200k new acceptance points (to 400k) added since the country’s demonetization in November 2016. [With only 2.5mn merchants out of some ~60mn accepting electronic payments, the opportunity is vast]. To complete a transaction, a consumer opens the mobile app on her smartphone and scans the vendor’s dedicated QR code (per below), grabbing the merchant’s ID and “pushing” a payment to him through the mobile app. [Alternatively, a tokenized QR code is sent to the consumer’s phone, which the merchant scans to “pull” a payment. QR codes, while uncommon in the states, are a major payment acceptance medium in Asia.]

Furthermore, by attaching a smartphone dongle (ha! dongle…), the merchant can use his smartphone as a payment acceptance terminal. Relative to a traditional card machine, the setup costs are 65% cheaper and the time to get up and running goes from days to minutes. I would expect the ease of merchant onboarding to drive terminal density, portending greater electronic payment adoption, per this interesting exhibit from Visa’s recent Investor Day….

This graph shows that card payment volume as a percent of personal consumption expenditures is positively correlated to terminal density. The kink in the graph suggests that there is a critical mass of terminal density at which point card payment volume penetration advances along a steeper trajectory [the exhibit labels the Y-Axis with card payment volume penetration, but as discussed above, the actual physical card is just a medium through which electronic payments occur…what we’re really interested in is electronic payments themselves, whatever the medium], which is what you might expect given the network effects at play [cardholders <--> merchants <-> card issuers]. The second salient takeaway is that the majority of the blue dots are still to the left of the kink.

But even while the smartphone has lubricated merchant acceptance and thus expanded the market, it has also introduced competition. Clearly, in many developing economies, the smartphone will be the primary medium through which off- and online transactions occur. And as I noted in a previous post, in India….

“Given the spoils of successfully establishing a 2-sided network in such a huge market, competition is intense. Generally, outsiders have found it hard to establish strong mobile payments footholds in developing markets, which tend to be dominated by local champions; hence, Ant Financial’s investments in local market incumbents rather than organic builds. To drive electric payment adoption in less populated regions of the country, the Reserve Bank has also approved the conception of “payment banks,” which are financial institutions that can’t make loans and exist for the purpose of accepting deposits and offering mobile banking and issuing debit and ATM cards. And of course there is an increasingly crowded, aggressively funded field of mobile payments/e-commerce hybrids with deep toeholds, particularly Paytm [200mn users and aspirationally 5mn merchants by year-end(?); according to the company last November, the company now does more daily transactions than debt and credit cards] but also MobiKwik’s [30mn+ users as of Aug. 2016 with annualized GMV is set to hit $10bn this year]; Snapdeal [FreeCharge], Flipkart, PayU Payments, Ola Money, and many others offering offline payments, P2P transfers, recharges, bill payment, and, on the other side of the network, merchant services.”

Paytm’s network of 200mn users and 5mn merchants dwarfs the 30mn credit cards/70mn debit cards used in POS and 2.5mn merchant acceptance points today. [technically, there are 840mn debit cards outstanding, but the vast majority, 770mn, are used solely to access cash from ATMs], and the company may leverage its position as the leading payment app to eventually become a full-service bank (with its “payments bank” representing an intermediate step).

But this is really one instantiation of a larger trend in global payments, which is the rise of new layers of payments middlemen in the online space. There are two important concepts here: modularization and platforms. You offer your application as a module that easily integrates into other platforms to drive increased adoption, which is critical to fostering an ecosystem around your application. This has resulted in a complex web of uneasy partnerships with would-be competitors.

Let me try to be more concrete about this by tracing the daisy chain of nested ecosystems starting with my baby, scuttleblurb.com. I use the WooCommerce plug-in to run my online store. WooCommerce powers about 30% of all online stores, more than any other platform (according to them anyways). They integrate with hundreds of free and premium extensions and can be custom configured and scaled as well. As a subscriber, you probably noticed 3rd party payment mediums like PayPal and Stripe. I didn’t separately integrate those. Those already came bundled into WooCommerce. WC is a platform because the more websites that download WooCommerce to run their online stores, the more developers build useful extensions for it, which in turn drives more downloads. PayPal, one of many integrations into the WooCommerce ecosystem, is itself an ecosystem. From my PYPL post from a few months ago:

Both same side and 2-sided network effects, and the winner-take-most dynamic they engender, apply. PayPal offers peer-to-peer transfers (PayPal and Venmo) and commerce that involve self-reinforcing consumer/consumer and consumer/merchant engagement – the more consumer accounts PayPal secures, the more important PayPal adoption is for merchants, and vice-versa. And the more services PayPal offers each side of the network – for instance, P2P payments, remittances, online/in-store purchases, bill pay, personal loans on the consumer side and processing, rewards, invoicing, and working capital on the merchant side – the stickier the relationship and the better the engagement.

And then as you know, last summer PayPal struck partnerships with Visa and Mastercard to expand its presence into offline retail. And this PayPal partnership is one of many partnerships that Visa has struck with other commerce enablers/platforms like Stripe, Square, and Adyan (not to mention broader platforms like Amazon, Facebook, Android, and Microsoft).

[I will focus on Visa below, but unless I explicitly state otherwise, you can assume that Mastercard is pursuing the same initiatives]

V’s open partnership model is a major change. VisaNet, as sophisticated and broad as it is, operated as a tightly restricted network with unidirectional flows (pulling money from one account and moving it to another) and limited functionality for those accessing it for most of its life. But now Visa has modularized its network (management actually began talking about this as early as 2010), decomposing VisaNet into its core building blocks, providing a set of APIs (over 60 web services/APIs available through a developer portal that launched in 2016) that financial institutions, platform operators, and payment enablers can use to interface with Visa’s network and services to create a wide variety of interoperable solutions. Ditto for Mastercard.

One example is the all-important token API. Tokenization takes the 16-digit primary account number of the card that we’re all familiar with and replaces it with unique encrypted numbers (“tokens”) that can put placed inside all kinds of digital devices and applications (“token requesters”) like mobile wallets (the issuer’s wallet, Apple Pay, Android Pay, PayPal, etc), connected devices, Visa Checkout, QR, and Card on File (payment credentials you have on file at Amazon or Netflix). Turning every connected electronic device and e-commerce site into a potential payments acceptance terminal is a major BHAG for V and MA. The card issuing bank connects to Visa once and can then push these tokens out to all these token requesters on behalf of their customers or the consumer can log into her mobile banking app and push these credentials herself. In an increasingly fragmented electronic payments landscape, where transaction enablement is no longer confined to plastic cards, the ability to conveniently push credentials to whatever device or app gives Visanet reach.

There are certain areas where V/MA compete directly against the very companies with whom they are partnering. For instance, Visa Checkout (24mn enrolled accounts / 300k+ merchants) and Mastercard’s Masterpass (90mn / 340k) are alternative options to the PayPal payment button you see at online checkout….though, with 200mn+ enrolled accounts and 15mn+ merchants, PayPal completely dominates V/MA. And everyone in the payments space is stepping up their merchant and issuer services (marketing, strategy, benchmarking, security, consulting, invoice and payment processing for SMBs through The Mastercard B2B Hub). Mastercard, for whom services comprises over 20% of net revenue vs. ~10% for V, has been particularly vociferous about this opportunity.

But essentially, Visa and Mastercard are entrenching themselves as the very first layer of disintermediation, the basic and indispensable infrastructure underlying the entire payments ecosystem, whatever the country, whatever the medium. And it seems increasingly the case that various payment providers will just plug into V/MA’s secure pipes while they themselves work on improving the customer experience. I think this also applies to the “mega-platforms”, for the most part.

As I previously noted:

“The fog of apprehension concerning whether major online social and mobile platforms – Android, Facebook, Apple – would claim payments for themselves, is burning off, giving way to an ever cooperative landscape in which significant social/mobile platforms are offering payments functionality as a means to the end of fostering user engagement, but are not themselves looking to payments as a separate revenue stream…

Given broad consumer adoption of PayPal’s for online payments, merchants who don’t have the critical scale to run an in-house payments platform (basically, all online merchants except for Amazon) adopt PayPal to ease the checkout friction that crimps sales [the typical cart abandonment rate is somewhere between 60% and 80%]. Facebook and Google have the user base to, in theory, enable their own online payments platform, but the predominant preoccupation of their ad-driven business models is capturing user attention, not skimming basis points on payments transactions. Amazon, on the other hand, has both the scale and the business model to justify owning payments facilitation because a) an Amazon wallet already has a killer app – the growing and almost impulsive transaction activity taking place on Amazon itself…which actually renders the wallet broadly useful to consumers and b) fees siphoned off to a third party payments facilitator sum to real money when selling ~$300bn of goods every year.”

B2B/B2C and push payments

The ability to push real time payments on Visa’s Direct Rail (rather than just pull payments from the cardholder’s account) has been around for a decade overseas and has only recently gotten traction in the US. Around 1/3 of Visa’s 3bn cards activated with real-time push now. Push payments are a $10tn opportunity in the US, $1tn P2P / $9tn B2C. A few examples B2C push payments use cases: with Square Instant Deposits merchants can have sales proceeds instantly sent to their debit cards rather than waiting for Square to ACH that money every Tuesday; Allstate, after processing claims, can push money directly natural disaster victims’ cards. Venmo and PayPal recently announced that they are integrating into Direct Rail so that consumers and merchants can immediately transfer funds from those Venmo/PayPal to their bank accounts.

Mastercard has had a version of this for years, Mastercard Send, but also recently began offering an alternative set of rails for B2B and government transfers though Fast ACH [ACH – Automated Clearing House, an electronic network that processes electronic payments, debit and credit, between banks. It’s typically used in B2B and large C2B payments like mortgage payments, insurance premiums and the like], per its recent acquisition of Vocalink, which operates UK’s ACH and ATM network and sees over 90% of the UK’s payment flows. Fast ACH’s real-time transfer capability is clearly superior to the archaic batched processing method that characterizes traditional ACH networks, which can result in transfer times of 4-5 days, and a growing number of countries are adopting it.

Unlike Visa Direct, which runs on Visa’s card rails and allows for cross-border transfers, ACH is a local market solution. To enable Fast ACH in other regions, MA/Vocalink will have to port the software and processes country by country, which they’ve had some success doing. The ACH route is more focused on large B2B and government transfers, which Mastercard claims are growing at 2x-3x the rate of consumer transactions and for which ACH is already the de facto solution [Mastercard is buying and extending the rails where B2B payments flow today while Visa is trying to move those flows to its card rails]. Checks represent half of B2B payments in the US, so there is considerable white space here.

Interchange

Interchange fees have been subject to a growing amount of regulatory and antitrust scrutiny over the years. The Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, which went into effect October 2011, capped debit card interchange rates at $0.21 + 0.05% (+1c for fraud protection) for issuers with assets greater than $10bn, from around 1.55%-1.6% + 4c/5c per transaction. Regulation is just a given in this sector – of Visa’s top 60 markets, 42 have regulated debit and 38 have regulated credit interchange.

[Not all government intervention works counter to the interest of card networks. Visa’s management cites at least 20 governments that have actively put incentives in place to push its citizenry away from cash, giving tax authorities better visibility into income and crimping black market activity. South Korea has mandated card acceptance and provided tax incentives for merchants and citizens adopting electronic payments. In Uruguay, citizens receive 4% cash back from the government when paying with debit while Argentina has mandated merchant acceptance of debit.]

A critical point here is that while Visa and Mastercard set the interchange rates, neither company’s revenue is explicitly pegged to it, so interchange caps don’t directly hit the card networks. The concern with Durbin was that lower interchange fees would prompt bank issuers to push back on fees they paid to the card networks. But this of course ignores the enormous bargaining power that Visa and Mastercard wield as an effective debit duopoly in the US. Bank issuers of course are also a pretty consolidated bunch, with the top 3 credit card issuers claiming almost half of credit card balances and the top 3 debit card issuers accounting for nearly 3x the purchase volume of the next 7 largest, but why duke it out at all when there are plenty of powerless bank customers from whom to extract value?

Pre-Durbin, debit issuers earned around 130bps on interchange debit transactions and paid out ~8bps in network fees…it was simply not worth the fight. Before Durbin went into effect, bank issuers admonished that they would recoup lost interchange fees by screwing their customers elsewhere, which is exactly what they did. To compensate for the loss of interchange fees, banks simply levied checking account fees, implemented higher minimum balances, and reduced rewards on debit card spending. Small dollar purchases were also penalized…you can do the math and see that for transactions under $10, the amendment results in a higher interchange fee. And at least according to this recent study by the International Center for Law and Economics:

In short, our findings in this report echo and reinforce our findings from 2014: Relative to the period before the Durbin Amendment, almost every segment of the interrelated retail, banking and consumer finance markets has been made worse off as a result of it. The Durbin Amendment appears on net to be hurting consumers and small businesses, especially low-income consumers, while providing little but speculative benefits to anyone but large retailers.

The Durbin Amendment only applies to debit cards, so there’s always the chance that caps get imposed on credit interchange, but it seems tough to make that case based on what appear to be neutral to harmful effects from debit interchange regulation.

European regulators have gone a step further, reducing the credit interchange rate from 0.5% to 0.3% in addition to a debit cap of 0.2% in mid-2015. Following demonetization, India slashed merchant discount rates from [0.75% to 1%] to between [0.25% and 0.5%] (depending on transaction size) in order to drive merchant adoption. And before that, Australia cut credit interchange fees by half in 2003. These are hardly the only examples of regulatory interchange interference. We’ll see what happens in India but at least in Europe and Australia, as in the US, issuer banks have simply levied fees and reduced rewards programs to offset interchange reductions. On top of these interchange caps, both US and European regulations have made it easier for merchants to route transactions to competing networks, among other stipulations apparently detrimental to V/MA.

And yet, despite all this, the actual harm to Visa and Mastercard has been indiscernable. Neither company breaks out debit vs. card revenue by country, so we can’t get too granular, but the bottom line is that payment volumes at both companies across debit and credit have compounded at a ~high-single/low double digit clip with growth across all regions since 2010 even after factoring in significant currency headwinds, while service fee yields have been flat to slightly positive and net revenue yields have expanded (at least partly a function of growing service revenue). So, the market has spoken, the V/MA moats have been tested. The interchange fee cuts, as significant as they’ve been for banks, have not meaningfully impaired profitability for the two dominant card networks (though, of course, we can’t see the alternative world where no there is no regulatory interference).

Opportunity

Visa will tell you that there’s a trillions and trillions of payment volume in new market segments like P2P ($5tn), G2C/B2C ($5tn-$10tn), and B2B (this is huge, > $20tn, largely ACH-based, hence MA’s acquisition of Vocalink). Against Visa’s $7tn of payment volume today, it’s a massive opportunity. Fine. But, it’s also certain that all this incremental volume will come on board at much lower cents/$PV….let’s just focus on the addressable PCE for now.

As mentioned, excluding Russia and China, there’s about $14tn of cash/check (vs. around $27tn in addressable PCE) for the taking, nearly 80% of which resides outside North America, with APAC ex. China representing the largest chuck at $4tn. To iterate, payments is a local market that requires feet on the ground driving merchant acceptance, establishing relationships with regulators, and inking deals with issuing banks. The positive externalities that drive scale mostly perpetuate within borders….electronic payments dominance in developed, well penetrated markets does not necessarily confer comparable advantages in developing countries. Both Visa and Mastercard understand this well. But they are also competing against local schemes. For instance, in India, a huge $1tn cash opportunity, the RuPay card network was launched in 2012 by the National Payments Corporation of India (a non-profit entity owned by a consortium of major banks, some state owned) to combat an apparently exploitative V/MA duopoly, and currently has 35% of Indian card share vs. 28%+ for Mastercard, which latter was forced to cut prices in 2014. Both Visa and Mastercard have complained about the government’s preferential treatment of RuPay, per this remark from a senior Visa official in India:

“The only reason RuPay has added so many is not because it is cheaper, but because there is an invisible mandate from the government to issue only RuPay cards. More than half of the cards issued have not been used. NPCI can claim to issue millions of cards. But these cards are not as a result of competition, but due to a monopoly.”

Since the Elo card was launced in 2011 as a JV by the three largest banks in Brazil, V and MA’s combined market share of active debit cards has declined from 97% to 80% (though, they still have ~90% of all credit cards).

V and MA still have some serious advantages though. A globally accepted card becomes increasingly relevant as incomes start to rise and cross-border travel escalates (good luck using your RuPay card anywhere else but India) and the level of data and technology underpinning the security of V and MA’s networks is without parallel among local schemes. For both V and MA, currency neutral payment volumes have grown by mid-teens over at least the last 3-4 years, and as mentioned, consolidated pricing (service fees as a percent of payment volumes) has not deteriorated. Yes, issuer incentives have trended upward but both companies have more than compensated for this on cross-border, service, and processing fees such that net revenue yields have ticked higher.

Visa Inc.’s acquisition of Visa Europe [€16.5bn, consisting of €11.5bn cash / €5bn convertible preferred and €4bn in potential earn-outs], which closed in June 2016 and expands V to 38 European countries, provides some opportunities to wring value out of a relatively inefficiently operated member-owned association….notably $200mn in synergies (~30% of VE’s opex) by FY20 as V slashes redundancies, extends its own technology platform/infrastructure to VE, and restructures client contracts (i.e. cutting rebates) [for the benefit of the issuing banks that owned VE, net revenue yields at VE were only 9bps(!), less than 1/3 the ~28bps recognized by V]. When we strip out the royalties that VE pays to Visa (which will obviously be eliminated in consolidation), VE operating margins are around 50% vs. 65% at V, which management claims can be leveled by FY20. I’m going to assume that they get most of the way there (Visa Inc., too, was once a member-owned entity that successfully transitioned to a commercial model) on high single digit payments volume growth and some net revenue yield expansion (to ~13bps) over the next 7 years.

That gets to me around $2.3bn in VE EBIT in year 7. Holding currency constant, if I grow ex. VE Visa payment volumes by ~10%/year (a deceleration vs. the last few years), assume net revenue yield declines a little every year and 80% contribution margins, I can model my way to $21bn in EBIT. As always, you be the judge of how reasonable this is. Basically, I’m betting that all the payment platforms, devices, and competing local rails notwithstanding, the value of V’s global scale, security features, and technology will justify stable pricing over time.

With no buybacks or debt paydown (unlikely), you can get to $6.10 in year-7 EPS with 40% of today’s market cap generated in cash over that time frame. You can model MA similarly and see that combined, the two companies will have ~$20tn in payment volumes on their rails while addressable global PCE grows to around $37tn at that time, without even considering all the P2P/B2B white space I alluded to. 25x year-7 earnings, tack on the net cash at that time, and bake in the dividends, and you can impute ~9% annual return off the current price.

Bitcoin

Cryptos are far too volatile to effectively function as currency today and validating transactions across a distributed network is less efficient than doing so at a central node. Visa’s network processes nearly 1,700 transactions per second, with a peak capacity of 50,000+. In theory, bitcoin’s blockchain can handle 7. Ethereum’s can do 20. Ripple’s can apparently sustain 1,500. And then there’s the generic chicken-egg challenge of spinning up any two-sided market. So for the time being, I don’t see cryptocurrency blockchains as a clear-and-present threat to the major payment networks…but I don’t want to be too sanguine about this, as crypto adoption looks an awful lot like a disruptive process, wherein low-end solutions meeting the threshold needs of a marginalized segment (in this case, unbanked consumers living under rapacious political regimes, transacting with unstable currencies) at lower cost. [Separate from the cryptocurrency discussion, Visa and Mastercard are piloting APIs connected to internal blockchains for high-value B2B inter-bank transactions and smart contracts].

The appeal of cryptocurrencies as an asset class, however, is both understandable and reasonable. The total value of all cryptocurrencies is around $150bn, compared to US M2 of $13.6tn and global M2 of ~$70tn. Of course, as with any asset whose price today reflects a wide distribution of outcomes, betting on any single crypto, let alone cryptos as a group, is a highly speculative proposition. But calling something “speculative” is not the same thing as calling it a bubble, as vaunted financiers and investors have been quick to do recently. Rapidly rising prices might be one symptom of a bubble and even a necessary condition, but this says nothing about the relationship between sustainable demand and price. Predictably, opinions about bitcoin seems to cleave cleanly along generational lines. The “get off my lawn” sentiment resonates with me on an emotional level. I find the frothy righteousness emanating from growing swarms of crypto evangelists completely insufferable and frankly, I’m annoyed at myself for even writing this. But, even so, I can’t recall a single Bitcoin hater offering an good explanation backing his System 1 bubble claim. And I’m not talking about the pedestrian concerns surrounding regulation and safety that accompany any earthshaking technology in its nascent phase, but rather arguments that impugn the core value proposition.

It seems strange speak of gold as a sacrosanct reservoir of value while also denigrating bitcoin. As a scarce asset immune to the debasing proclivities of central banks and practically impervious to subversion, bitcoin, like gold, in principle acts as a store of value and a medium of exchange. As part of a distributed system that incontestably validates transactions without double counting, it is a unit of account. And unlike gold, bitcoin can’t be haphazardly seized by despotic governments. Gold emerged out of cosmological happenstance(1), proved practical as a currency on a non-digitized earth for centuries, and persists today as a widely acknowledged store of value largely due to historical momentum. But imagine this from the perspective of an alien species colonizing earth. Given the state of technology today, would gold occupy special sanctuary in their minds as a store of value any more so than platinum or rhodium or palladium? Or, for that matter, a currency arising from an intelligently designed, broadly distributed network of checks and balances?

[(1) According to one theory, several times over the last several billion years, one neutron star collided with another, creating the conditions for iron nuclei debris to get bombarded by neutrons that decayed into protons, transmogrifying iron into a handful of heavy elements, which were carried by meteors to Earth, where they embedded themselves in the Earth’s crust. One of those elements was gold. Despite the numinous import historically assigned to gold by various cultures, there is nothing intrinsically or cosmically interesting about it. It just so happened that gold’s proximity to the Earth’s surface made it readily accessible and its physical properties – immutable, relatively rare, rust-free – rendered it capable of lubricating trade and tallying debts. We agreed that this inscrutably generated element should be parochially meaningful, and so it was. All currencies are born of consensus among transacting parties. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are no different.]