[AEP.V] Atlas Engineered Products

In part 3a, I provided an overview of pre-fabricated trusses, namely the value they offer homebuilders over traditional stick building and what’s involved in the transition from Phase 1 manufacturing (automated saws and lasers) to Phase 2 (robotic systems). You’ll want to read that first or much of this write-up won’t land.

Atlas Engineered Products, a thinly-traded nanocap based in Canada, is the only publicly traded truss pureplay I’m aware of. It was founded by its current CEO, Hadi Abassi, an Iranian immigrant who in 1999, after stints cleaning floors at McDonald’s and selling windows, paid C$50k for a small truss plant in Nanaimo (Vancouver Island), taking it from less than C$100k in revenue to nearly C$6mn over the next 16 years. He observed that in Canada, truss manufacturing was scattered across mom-and-pops and took Atlas public in 2017 through a reverse merger with the aim of rolling them up.

Management estimates that there are more than 200 truss companies in Canada, collectively doing about $2.5bn of revenue. I haven’t found any reliable data on the overall market and even Atlas’ own estimates have varied over time (in 2018, they estimated “over 300 small and medium-sized owner managed and operated businesses with revenues in the range of $3-$5 million per year”). Still, by all accounts the industry is fragmented, with more than enough needle-moving M&A opportunities for Atlas, who operates just 8 facilities. The low value-to-weight ratio of trusses makes them uneconomic to transport more than a few hundred miles, so each plant serves a geographically constrained area. While switching costs aren’t insurmountable, the collaborative design aspect with homebuilders fosters some degree of customer loyalty. So, rather than degrade the economics of a market by adding more capacity and trying to steal away somewhat sticky volumes, Atlas, like BFS, is acquiring existing manufacturers, many of whom are run by founder-operators seeking an exit anyway.

Today, 7 years since its IPO, Atlas owns 8 plants, the 1 plant in Nanaimo that Hadi acquired in 1999 plus 7 more picked up through acquisition (excluding Alberta Truebeam, whose assets were relocated to other locations).

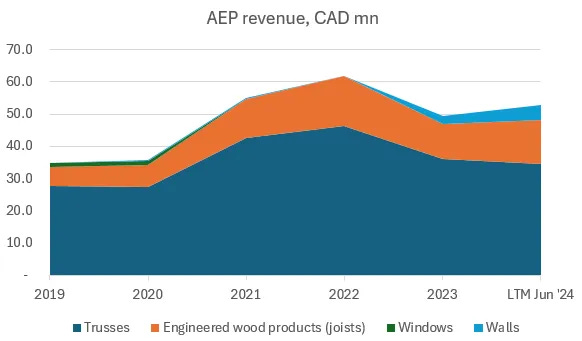

Acquired plants continue to run under their old banners as part of decentralized regional hubs, while a lean corporate office1 centralizes non-operational functions like finance, M&A, and IT infrastructure across them. Atlas has so far restricted acquisitions to 4 provinces (British Columbia, Ontario, Manitoba, and New Brunswick) and avoided large, crowded metros in favor of less sparsely populated markets with comparatively limited competition. It has expanded into engineered wood products and wall panels, but trusses still account for ~2/3 of total revenue.

With the exception of Leon Chouinard & Fils (LCF), purchased last year for C$29mn, these targets were doing less than $10mn in revenue. Most were unsophisticated and still reliant on manual processes. I recently spoke with Dirk Maritz, the CEO of Atlas from Nov. ‘18 to Jan. ‘212, who oversaw the acquisition of 3 plants during his tenure and spearheaded the move to Phase 1 automation across the organization. He conveyed that some plants hadn’t yet adopted design software, were still dimensioning planks with measuring tape, cutting planks with outdated saws, and laying them on antiquated tables. Off this low starting point, Atlas catalyzed significant volume and productivity gains through a phased rollout of upgraded equipment, laser systems, and software. A C$5mn revenue plant outfitted with C$500k of Phase 1 upgrades could see C$2.5mn to C$3mn of incremental revenue with meaningful cost savings to boot. At one location, simply installing new truss tables that could handle larger truss designs lifted revenue by 15%-20%. Atlas realized further gains by consolidating sales and finance functions and funneling demand from national builders to the acquired mom-and-pop plants.