[ALGN] Invisalign: Still the Clear Choice?

MBI and I recorded an episode of Never Sell recently (Global Payments, AI and Software, OpenAI and Anthropic Bubble?) (Spotify, Apple, YouTube, RSS feed)

AI-generated podcast conversation: Spotify, Apple, direct link

AI-generated summary: This report traces the rise, challenges, and current state of Align Technology in the clear aligner market. It shows how Invisalign transformed from a mocked niche product into the category leader by vertically integrating scanners, software, and manufacturing, and winning over orthodontists through efficiency gains and consumer demand. Competitive threats like DIY printing and DTC players (SmileDirectClub, Byte) proved unsustainable, but Align now faces new pressures: weakening orthodontic traffic, price competition (notably from AngelAlign), and margin erosion. Still, it retains powerful moats built from scale, brand, data, and product innovation (IPP, MAOB, direct 3D printing, iTero Lumina).

I.

When I last discussed Align Technology back in April 2021, the market for clear aligners – those series of removable plastic trays applied in sequence to fix crooked and crowded teeth – was booming, with volumes expected to grow by 20% to 30% for as long as anyone could tell. There were ~20mn malocclusion cases started per year, ~80% of them addressed through the medieval apparatus of metal wires and brackets, creating a deep well of easy pickings for a growing slew of clear aligner providers.

The largest and oldest among them was Align, which came to market in 1999 with Invisalign, a brand that has since become a deonym for its category. At the time, clear aligners were a joke, mocked by trained orthodontists who derided the idea that wearing plastic trays could ever approximate the precision **of installing brackets and tightening wires by hand. And for a while they were right. Well before Align was launched by two Stanford GSB students, orthodontists had already tried removable appliances for simple tooth movements, with limited success. Even Invisalign could only handle minor corrections at first. A device of questionable merit, suitable for a minority of cases, clear aligners went ignored by serious companies, like Dentsply and 3M, who sold traditional braces to serious doctors.

With orthodontists skeptical of aligner technology, Align began appealing directly to consumers, investing a significant amount of its $130mn of venture funding (a lot of money in those days!) into national brand advertising. The pitch: besides being more discreet than metal braces, clear aligners were more comfortable, as they didn’t grate against soft tissue, and more convenient, as they didn’t require as many mid-treatment checkups. Patients began to ask for Invisalign by name and orthodontists began offering it in turn. As successful outcomes accumulated across increasingly complex malocclusion cases, still more orthodontic practices were drawn into the fold. Manufacturing capacity that had been worryingly underutilized, scaled sufficiently by the early 2000s to reverse Align’s negative gross margins.

But even if treatment efficacy weren’t in doubt, why would orthodontists bother to learn a new system and pay 5x to 10x more than for time-tested wires and brackets? Orthodontists might charge anywhere from $6,000 to $8,000 for a comprehensive malocclusion case. Some price clear aligners on par with traditional braces, while others tack on a premium. Either way, they earn far higher margins on braces, which cost them just $200 to $300 per case, than on Invisalign, where lab fees run $1,000 to $2,000. The trade-off only pencils if Invisalign meaningfully reduces chair time, freeing doctors to see more patients and thereby offsetting the slimmer profit per case.

Invisalign treatment begins with a 3D intraoral scan of the patient’s dentition, captured with Align’s iTero device. The scan is shot over to an overseas Align lab, where technicians – originally, Pakistani computer technicians selected for their skill at playing the video game, “Doom”1 – design a digital treatment plan in ClinCheck, Align’s proprietary modeling software, mapping a series of controlled tooth movements to corresponding aligners. The orthodontist then reviews and approves the plan in ClinCheck, after which the aligners are produced at one of Align’s manufacturing facilities.

Two things stand out here. First, the entire Invisalign workflow is controlled by Align: from the iTero scanners2 that image the teeth (orthodontists cannot submit Invisalign cases with third-party scanners), to the ClinCheck software technicians use to design treatments, to the manufacturing facilities that produce the physical aligners. Second, within this setup, an orthodontist plays a mostly supervisory role. A chairside assistant, typically an hourly worker, takes the scan while an Align technician designs the plan. The orthodontist might spend, oh, ten minutes or so scrutinizing and tweaking the treatment and another few minutes on each periodic follow-up.

This is much easier on an orthodontist’s schedule and hands than twisting and bending wires. Management claims that compared to braces, Invisalign treatment is, on average, five months faster and requires 35% fewer doctor visits. And according to this widely cited study from the American Association for Dental Research (AADR) 2012 Annual Meeting: “conventional braces required about 2.6 more visits than Invisalign, treatment for 2.4 months longer, 1.1 more emergency visits, 9.7 minutes more in chair time, 1.2 minutes more emergency doctor time, and 86.2 minutes more in total chair time (P < .01 for all)”. Compared to Invisalign, braces require longer treatment times, more frequent visits, and more chair time per visit. Those minutes add up!

As orthodontists bought into the throughput-enhancing benefits of Invisalign, whose treatment efficacy was at the same time being born out over a growing number of successful cases, Align’s revenue boomed, attracting a growing number of competitors. Orthoclear, founded by one of Align’s co-founders, swooped into the market in 2005 on the back of stolen IP and swiftly clipped 20% of the market. ClearCorrect emerged in 2006 as a cheaper, dentist-centric alternative to Invisalign.

Neither these, nor any number of other emerging challengers, managed to sustainably dent Align’s dominant share. Orthoclear was sued into oblivion within two years of its founding. ClearCorrect spent roughly half its existence fending off Align’s patent-infringement claims before being acquired by Straumann in 2017, where it remains buried beneath a larger portfolio of orthodontic products, struggling to turn a profit. Envista, the former dental products division of Danaher and the leading vendor of wire-and-brackets, markets a clear aligner brand, Spark, that is about a quarter the size of Align by revenue and also unprofitable. Henry Schein’s Reveal, meanwhile, is less than half as large as Envista’s. 3M’s Clarity is a speck within the vast expanse of its corporate parent and Dentsply Sirona’s SureSmile has failed to gain any meaningful traction. Part of the bear case for Align was that Envista, Henry Schein, and the rest would leverage entrenched relationships with doctors – to whom they sold braces, dental equipment, and other products – to edge out Invisalign with their own aligner alternatives. So far, this strategy has been a bust across the board.

II.

But then starting around 2017, as key patents related to digital treatment planning and CAD technology expired and as numerous copycat versions of Align’s business model fell by the wayside, two orthogonal approaches to the aligner market emerged: DIY aligner printing, led by uLab, and DTC aligner sales, popularized by SmileDirectClub.

DIY has always seemed like a non-starter to me. It’s much cheaper than ordering from third party producers, but it also consumes time and labor. I also find it hard to imagine too many orthodontists possessing the confidence to print resin molds, vacuum-form plastic material over them using a thermoforming machine, cut excess material away, and polish the tray edges. Supporting this intuition, uLab3 invested in scale manufacturing in 2021, six years after its launch, which I don’t think they’d have done if in-office printing were taking the market by storm4. While some orthodontists offer DIY as an option alongside other commercial solutions, I’ve seen no evidence of it being increasingly adopted as a standard.

The DTC model, on the other hand, was a far more salient competitive concern for Invisalign. SmileDirectClub burst onto the scene in 2014 and by 2019 was shipping close to half a million cases annually, a landmark that Align only breached after seventeen years. It was selling aligner treatments directly to consumers at a steep discount to prices charge by orthodontists while at the same time fueling brand awareness with lavish VC-funded marketing campaigns and a rapid rollout of freestanding locations. It even began partnering with Dental Service Organizations (DSOs) and persuaded Walgreens and CVS to host SmileDirect shops inside their stores. The aggressive startup’s early success inspired an explosion of imitators:

A few established players also got in on hype, scooping up various DTC upstarts during the COVID boom. Straumann acquired a majority stake in DrSmile while Dentsply Sirona shelled out $1bn for Byte. All DTC concerns from those glory days have since collapsed or been folded into a traditional, doctor-mediated model. It’s astonishing how a model so enthusiastically celebrated was so comprehensively decimated in such a short span of time. I mean, today literally no one even pretends that DTC is a viable route to market.

Post-fact prophets knowingly smirk at how stupid and wasteful the whole project was. But back then, SmileDirectClub was widely seen as the first promising challenger to the dominant incumbent in twenty years. Align had counter-positioned against braces by marketing directly to consumers. SDC drew out this initial touchpoint to its vertically integrated conclusion. Not only did it market to consumers, create treatment plans in proprietary software, and manufacture aligners – all things Align did – but it also sold those aligners directly to patients, financed their purchase, leased stores, and staffed technicians. Basically, SmileDirectClub assumed the costs that an orthodontic practice would normally bear, betting that consolidating all facets of treatment would produce superior customer journeys. Orthodontists, rather than interfacing directly with patients, were reduced to evaluating SDC-designed treatment plans through SDC’s telehealth platform.

As bound as it was by legacy ties to orthodontists, even Align was concerned enough about SDC’s competitive encroachment that it began opening freestanding showrooms to provide consultations, which management pitched as a referral channel to orthodontists but which orthodontists saw as the first step to their disintermediation. Doctors were pissed and SDC, whom Invisalign had been supplying with low/mid-tier aligners, sued, forcing Align into retreat.

The long-term bull case for SDC went something like: build case volumes through attractive price points, brand awareness, and easy accessibility; leverage that volume to achieve greater manufacturing scale and lower unit costs; reinvest those savings into acquiring more patients (er, sorry, “members”), in turn drawing more case-reviewing doctors, resulting in faster turnaround times and superior experiences that spark word-of-mouth virality, drawing in still more members who would eventually be cross-sold a growing number of ancillary products like toothpaste and night guards.

Nope!

In explaining the company’s unraveling, SDC’s management pointed to two culprits: first, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency framework severed the tie between impressions and conversions, crippling the efficiency of customer acquisition. Second, soaring inflation in 2021 crushed the discretionary purchasing power of SDC’s core demographic, households with a median income of $68k.

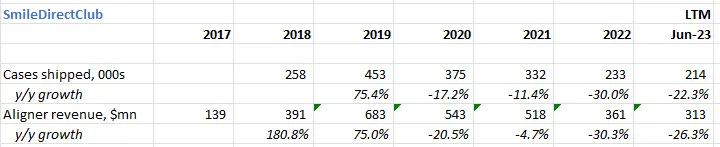

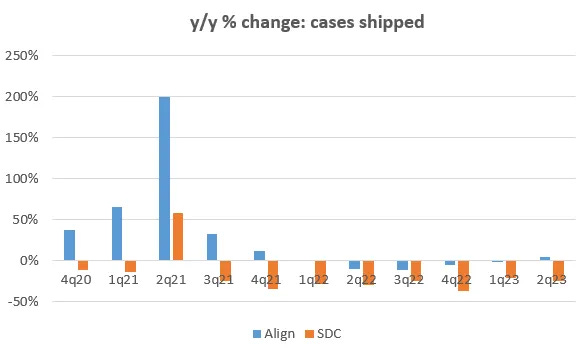

I don’t doubt these two factors played a role in exacerbating SDC’s woes, though I’m skeptical they alone account for most of gaping growth disparities between SDC and Align:

In 4q20, before the onset of ATT, SDC case shipments declined 12% y/y while Align’s surged 37%. And even as inflation dissipated to pre-COVID norms in 2023, SDC experienced huge ongoing deterioration in case volumes. And why didn’t SDC benefit from the frenzy of discretionary spending fueled by stimulus checks? Or the purported “Zoom effect”, cited by Align and others, where repeated video conferencing engagements during COVID prompted self-conscious scrutiny about the quality of one’s smile?