Booz Allen and the business of defense – part 2

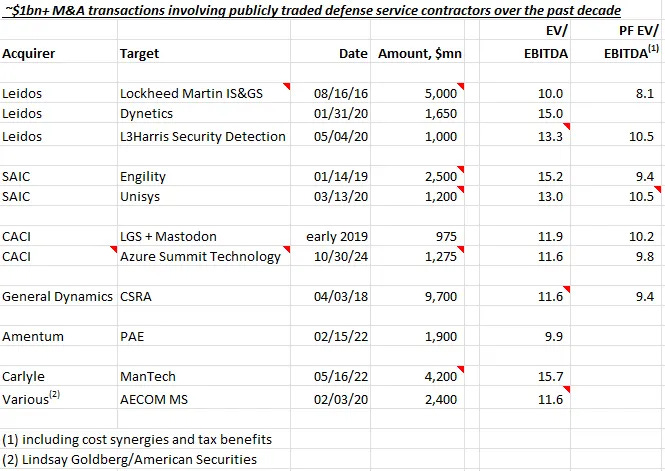

I left Part 1 with the observation that, starting in earnest around a decade ago, the federal government began encouraging procurement through a smaller set of omnibus vehicles that bundled a wide range of services – previously sourced piecemeal – under a single, flexible framework, tilting the playing field toward scaled contractors who could cover all parts of a technical engagement. In parallel, defense contractors have been migrating down the stack, moving from program management to systems integration to, increasingly, developing and owning products of their own. Those twin trends have unleashed a wave of M&A activity:

(Don’t take the multiples too literally. Some EBITDA figures are trailing, others are prospective).

All this consolidation activity was preceded by a landmark split. In 2013, SAIC was cleaved in two to avoid the organizational conflicts of interest (OCI) that arise when the same company advises the government on a program and also bids to execute it1. The larger, “legacy SAIC”, which took the name Leidos, inherited most of the high-tech contracts and tilted toward R&D heavy programs for mission-specific work related to national security, defense, and healthcare. The remaining part of SAIC, the “new SAIC”, served as more of a platform-agnostic integrator involved in IT modernization and played closer to the advisory end of the stack.

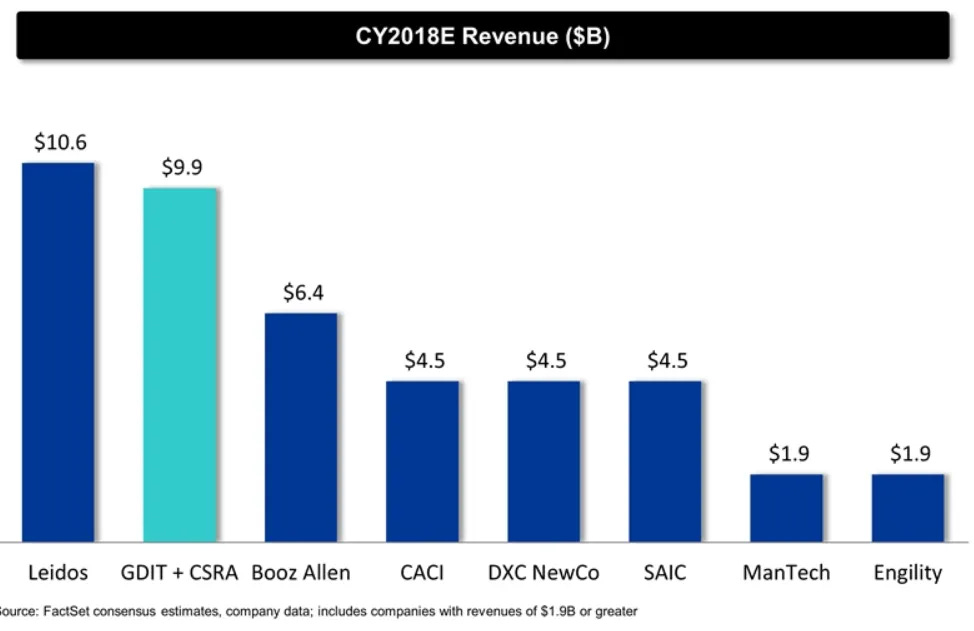

In 2016, Leidos re-created much of the large-scale IT services and systems integration work that had been offloaded to new SAIC during the split by merging with Lockheed Martin’s IS&GS division in a ~$5bn Reverse Morris Trust transaction that doubled its revenue, from ~$5bn to ~$10bn, and left Lockheed shareholders with 50.5% of the combined company[1] (the OCI conflicts that inspired the original SAIC split were apparently avoided in this combination)

Four years later, Leidos pushed deeper into hardware and applied R&D with two notable acquisitions: 1) Dynetics ($1.65bn; Jan ‘20), which brought product prototyping competencies in radars, weapons, and counter unmanned aerial systems, among other areas, as well as hard tech product lines addressing DoD priorities at the time (hypersonics, space, high-energy lasers, AI, microelectronics); and 2) L3Harris Security Detection and Automation Systems Division (~$1bn; May ‘20), which manufactured airport and customs screening technology, like checkpoint CT scanners, full-body scanning devices, and mobile inspection systems.

At around this time, SAIC began making waves of its own with the acquisitions of Engility ($2.5bn; Jan ‘19) and Unisys Federal ($1.2bn; Mar ‘20). Engility brought SAIC expanded access to intelligence and space, and pushed SAIC from its back-end enterprise IT perch closer to the action, with engagements that included validating flight software for NASA and modernizing satellite ground systems for the US Air Force. Compared to Engility, Unisys Federal ($1.2bn; Mar ‘20) – the federal IT services division of Unisys – sat closer to the enterprise IT side of the spectrum. Its core offerings included: ClearPath Forward, a platform for application modernization and cloud migration; InteliServe, an AI-enabled digital service desk that automates routine IT support; and Stealth, a zero-trust cybersecurity suite.

With Leidos absorbing Lockheed’s IS&GS business, General Dynamics IT – the government IT arm of a vast complex whose activities span business jets, nuclear-powered submarines, destroyers, tanks, weapons systems, munitions, and communications – found itself slipping from the upper tier of federal IT just as government spending was consolidating into multi-year megadeals that rewarded scale (as management put it at the time, “in a consolidating market, our thesis is that you either have to consolidate or get consolidated out”). In response, it paid $9.7bn for CSRA, which had spun-off of CSC and simultaneously merged into SRA International about two years earlier. CSRA was was essentially a slightly larger twin of GDIT, doing largely the same work – cloud migration, cybersecurity, enterprise IT operations, and managed services – for many of the same federal customers, albeit with different agency footprints. The transaction more than doubled the size of GDIT, from ~$4.5bn of revenue to ~$10bn, creating the second largest Federal IT consultant.

Source: CSRA Schedule 14A

Had General Dynamics not acquired CSRA, CACI2, which had submitted a competing bid, would have occupied the #2 spot instead (incidentally, CACI also tried to buy Lockheed’s IS&GS division in 2015 but lost the deal to Leidos).