Building materials: part 3a (BLDR, AEP.V)

Related posts:

Building materials: part 2a (LPX, JHX)

Building materials: part 2b (TREX, AZEK)

In Part 1 of this series, I described the steps by which an ocean of building materials are titrated out to end users. Below is a stylized illustration of the value chain from the perspective of BlueLinx, a two-step distributor, who breaks down railcar quantities of product into smaller portions that are parceled out to pro dealers, home centers, and other customers, who in turn supply homebuilders and contractors in local markets. Builders FirstSource (BFS), the main subject of this post, is a pro dealer (aka, “one step” distributor).

Source: BlueLinx

Building materials is a massive, diffuse space and certain sub-categories – roofing, cabinetry, plumbing, and flooring – are complex and large enough to support specialty distributors. BFS concerns itself with the structural components that comprise the skeleton of a house….framing lumber, OSB, engineered wood products, and floor and roof trusses, as well as complements like wall panels, siding, doors, and window frames.

Their $17bn of revenue is ~evenly distributed across 4 categories:

Lumber and lumber sheet goods consist of wood planks and OSB boards that builders use for onsite construction. Specialty building products & services is a catch-all bucket that includes siding, exterior trim, roofing, insulation, digital tools, as well as installation services.

Manufactured products (trusses and custom framing packages) and Windows, doors, and millwork (WDM) and are deemed “value-added” because here, BFS doesn’t just act as an intermediary between suppliers and users. In a controlled factory setting, they nail wooden planks into truss patterns; cut lumber to the exact specifications of builder’s framing design; carve intricate patterns into interior trim; and attach door slabs to hinges and jambs. By using such pre-fabricated components instead of building them onsite, homebuilders save time and labor through faster turnaround times. As a result, value-added products sell at a premium and enjoy much higher gross margins (~30%-35% vs. high-teens/low-20s for everything else).

Builders FirstSource has been transformed through so much M&A that I think of it less as a consistent, singular identity than a corporate name affixed to ever more grandiose expressions of the idea that pro dealers can better and more profitably serve builders by moving the production of structural components from jobsites to manufacturing plants and by offering a broad assortment of SKUs across a dense, nationwide network of branches. Originated as a division of Pulte Corporation, Builders’ Supply & Lumber (as they were then known) was acquired in 1998 by JLL, who bolted 23 companies onto Builders’ before taking the rolled up entity public in 2005, at the tippy top of the housing market. BFS was devastated by the ensuing crisis. Between 2005 and 2010, revenue collapsed by 70%, pre-tax profit margins of +7% flipped to -9%, and the stock lost 95% of its value. The company burned cash every year from 2008 to 2013. During this dark period, BFS managed to stay alive while many other lumber yards foundered. But they were certainly in no shape to invest in growth. M&A activity was more or less put on hold for 7 or 8 years, understandably so. After all, BFS had just fallen off a cliff and continued to rack up losses. Why would anyone want an even bigger version of that?

But by 2014, years into a tepid housing recovery, Builders began to flicker back to life. Losses inflected to profits and free cash flow dribbled out. Over the next decade, BFS didn’t merely resume its small-ball M&A program; they rage-acquired their way to the top, as if making up for lost time. Since 2004, Builder’s has spent $7.9bn on acquisitions, $7.8bn of which has been concentrated in just the last decade. Most of the ~68 companies companies they’ve purchased since inception have been in the $10s of millions, a handful in the hundreds of millions, all of them pretty much geared toward bolstering their presence in fabricated components and establishing footholds in new markets, consistent with their stated aims at the time of the IPO.

But two transformative acquisitions, accounting for 2/3 of M&A capital over the past 2 decades, merit special mention: ProBuild (July ‘15; $1.8bn; 5.5x post-synergy EBITDA) and BMC (Jan ‘21; $3.7bn; 8.4x post-synergy EBITDA).

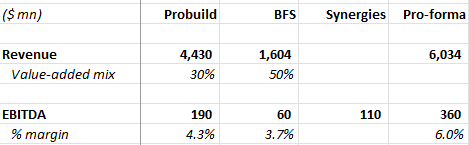

ProBuild was assembled in 2006 by Devonshire Investors, the private investment arm of Fidelity Investments, through the $1.1bn acquisition of Lanoga, the nation’s third largest materials dealer, and the $548mn purchase of Hope Lumber, a manufacturer of fabricated components. With $6bn of revenue, Probuild was nearly 3x the size of #3 BFS at the time. They spent several hundreds of millions buying more companies over the next few years until they too, were crippled by the GFC. After getting cut in half over the next 3 years, revenue had recovered to $4.4bn by 2014, a ways from its 2006 peak but still enough to make them the largest player in the industry:

(Some years later, Builder’s would argue that ProBuild ran a “higher-cost operation” and was more willing to pursue lower-margin opportunities. And yet, even with a much greater mix of higher-margin value-added revenue, BFS’s margins we no better than ProBuild’s, so who knows).

After taking a long breather on large scale M&A as it worked to de-lever its balance sheet (from net debt/EBITDA of 5x) and integrate a company several times its size, BFS acquired BMC in an all-stock deal that left BMC shareholders with 43% ownership of the combined company1.

Source: BMC merger presentation (August ‘20)

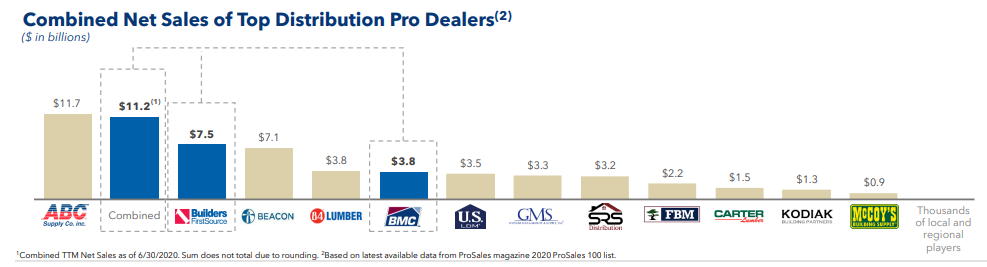

At the time, BFS was already the largest lumber and building materials (LBM) dealer in the US. The merger further advanced this lead, creating an industry giant with 3x the revenue of 84 Lumber, the #2 player (ABC Supply and Beacon, featured in the exhibit below, are typically regarded as specialty dealers. They overlap with LBM dealers to some extent but are mostly known for non-wood products, like roofing and gutters).

Source: BMC merger presentation (August ‘20)

Founded in 1987, BMC had grown to about half of Builders’ size through a similar acquisition-driven strategy, paying anywhere between ~4x-6x EBITDA for run-of-the-mill lumber dealers and ~5x-8x for value-added components manufacturers. Months after BFS announced its merger with ProBuild, BMC announced a reverse merger with Stock Building Supply (SBS), a competitor of nearly the same size who had also expanded through acquisition since its founding in 19222. The combined entity, with $2.7bn of revenue, stood a distant second to BFS/ProBuild.

As independent companies, both BMC and SBS were progressing along the same trajectory as BFS for basically the same reason – more markets, more value-added revenue, more local scale. BMC and SBS both had branch networks concentrated in the West and South, regions with year-round construction cycles. But each brought their own special something too. BMC had established a strong reputation in pre-cut lumber packages (planks of lumber cut to within 1/16th’s of a home’s design dimensions, piled in the order in which they will be used), with its Ready-Frame brand blossoming to more than ~$220mn in revenue just 3 years after being launched in the Pacific Northwest3. SBS had developed an “eBusiness” platform that enabled a web-based transactional front-end through which pros could browse inventory and place orders for pickup or delivery.

Following a mega-merger, it is not uncommon for homebuilders, who don’t want to be at the mercy of any single dealer in a given market, to shift some business to an alternative second supplier. But whatever the enlarged dealer loses in revenue it more than makes up for with enormous cost synergies. BFS and ProBuild realized ~2 points of synergies on ~4% EBITDA margins; BMC and SBS added ~2 points on 6%; and BFS and BMC created just over 1 point on 7%. The cost synergies are straightforward. They require no imaginative leaps. A merged entity can 1) consolidate overlapping branches and manufacturing plants; 2) cut duplicative overhead (you don’t need 2 ERPs, 2 CFOs, etc); and 3) combine rebate contracts for greater procurement savings, especially in value-added categories. When BFS merged with ProBuild, management estimated that those 3 buckets accounted 20%, 50%, and 30% of cost synergies, respectively. When they later combined with BMC, G&A savings were expected to again make up half the savings, with procurement contributing another 1/3.

So, the Builders FirstSource that we know today is a nested collection of rollups, each migrating up the value stack and reaching new markets in parallel before fusing together under a single corporate owner:

Source: BMC merger presentation (August ‘20)

At the time they went public in 2005, Builders FirstSource cited 84 Lumber, SBS, and ProBuild as its 3 largest competitors. Two of those are now in their fold. Still, even after decades of consolidation and with 3x-4x the revenue and locations of the second largest dealer, Builders claims just 13% share and competes with thousands of local and regional players.

BFS sells hundreds of thousands of SKUs across ~570 locations (more than 280 of which are value-added) in 43 states, boasting #1 or #2 share in 89 of the top 100 MSAs. Around 2/3 of revenue is tied to single-family home sales, another 20% and 13% to repair & remodel and multi-family structures4, respectively.

Source: Builders FirstSource Investor Day (December ‘23)

BFS sells to variety of end users but they prioritize national homebuilders like D.R. Horton, Lennar, and Pulte Homes (their top 10 customers, contributing 15% of 2023 revenue, was primarily made up of production builders), who have taken significant share in the largest MSAs since 2009 and are more inclined to use prefabricated components.

As BFS amassed scale and influence, they not only secured more bargaining power against two-steppers but increasingly sourced lumber directly from mills5 and value-added SKUs directly from manufacturers, keeping more margin for themselves. The more significant way Builders has evolved though, is in thinking about the homebuilder’s P&L rather than their own. BFS could have limited their activities to buying mixed lengths of lumber from mills; chopping them up to lengths required by builders; ensuring the right planks are delivered to the jobsite on time for the next build phase; and always staying in stock. But they extended to other facets of a homebuilder’s job: hammering lumber planks into frames and trusses; streamlining the build process to hasten turnaround times; providing installation services6 through third party subcontractors; and even managing a digital platform through which builders can not only order products and pay bills, but even 3D model projects and schedule workflows.

The most salient demonstration of Builders’ commitment to this project is their emphasis on value-added products generally and truss manufacturing specifically. At least 40% of BFS’ acquisitions since 2020 relate to truss manufacturing in some way.