[DF – Dean Foods] Levered Commodity Processor, Impending Challenges

Dean is a levered commodity processor sandwiched between fragmented but price-protected dairy producers and consolidated retailers, donating market share in a secularly declining market to undisciplined, subscale peers. Its stock trades for 16x management’s charitably adjusted EPS,1 a full market multiple for a narrow-moat business.

The environment in recent years beckons 2007-2010: 1) a period of rapidly inflating, margin squeezing dairy costs (2007-1h08) abruptly segues into 2) one of margin boosting commodity deflation (2h08/1h09) before transitioning into 3) a tepid demand backdrop that prompts retailers to discount their private label offerings and push-back on processors, eroding Dean’s branded sales and pillaging profitability. I think Dean could be entering phase 3.

Milk processors experience brief spurts of margin expansion when raw milk prices suddenly and unexpectedly careen but the governing rule, validated time and again, is this: as long as processing capacity remains in excess (as it has been and is), declining dairy consumption volumes will tempt market participants to concede price discipline to gain share. Dean will cut costs, sure, but it will mostly be running just to stand still. Lower raw milk prices eventually translate into profit-squeezing wholesale prices and margins mean revert in short order. Over longer periods, dairy processor margins are a downward sloping sine wave.

The bull case has long rested on excess capacity reduction (really, this was the thesis 16 years ago) led by Dean’s consolidation/rationalization efforts2 but has mostly ignored that: 1) much of Dean’s customer base has consolidated and flexed increased bargaining strength against Dean and 2) as Dean shutters distribution/processing facilities to chase utilization, it forsakes the benefits of regional density and penalizes itself with higher distribution costs.

Disaggregating profitability

Dean’s profits are a function of how many gallons of dairy it pushes through a per gallon profit spread, the latter driven by contribution margins per gallon and fixed cost leverage.

Here’s a simple high-level glance at Dean’s profitability, which, as you can observe, have fluctuated considerably over time. Coincident with an abrupt collapse in raw milk prices, Dean’s per gallon gross profits are now at a 7-year peak of $0.75, about $0.05 / gallon above average, which may seem like nothing until you consider that EBIT/gallon is just $0.10.

Note: Prior to the WhiteWave and Morningstar separations in 2013, gross margins are those of DF’s Fresh Dairy Direct segment.

Note: Dean’s volume by gallons disclosure is new and only extends back to 2012. I have estimated volume in prior years based on volume %-change disclosures.

The diagram below distills the hypothetical gallon price of milk up to retail:

(C) Class 1 Raw Milk (“Class 1 Mover”): This is the price Dean and other dairy processors pay farms/coops for their raw milk,3 mostly under 1 to 2 year contracts with minimum quantity purchase obligations. Regional prices – while subject to significant fluctuation – are regulated and supported by the federal government and various state agencies.4 After accounting for producer premiums and procurement costs, Dean typically pays way more than the statutory minimums. The Company adjusts wholesale pricing passed down to retailers monthly to sync up with input cost fluctuations, though there can be time lags. Rapidly rising raw milk prices are particularly pernicious to processor profits because they dually pressure margins and retard end volume when retailers pass them through to consumers (dairy, despite industry claims of its indispensable health benefits, is an elastic good). This is what happened in 2014, as heady demand from China and Russia buoyed the Class 1 mover…..before a terms-of-trade crimping ag/commodity downturn coincided with continued global dairy production to send raw milk careening the following year and delivering outsized gross profits to Dean in 2015. With Dean’s net leverage of 4.5x within striking range of its 5.25x covenant at the end of 2014 (management was in the process of renegotiating its leverage ratio covenant in 2014), we can only imagine how financially compromised the Company would have been were it not for this input cost deflation godsend.5

(B) Margin over milk: the per-gallon price charged by retailers to consumers less the price paid by dairy processors to producers. The division of this money pie between processors and retailers is tied to their relative bargaining strengths.

Observe below that margin over milk is inversely correlated to the price of Class 1 Raw Milk. That’s because milk is a relatively elastic good and raw milk price increases can’t be fully passed onto consumers without meaningfully compromising unit volume at the shelves (particularly at higher absolute retail price points). So, the preponderance of price escalations in Class 1 Raw Milk are absorbed by processors and retailers, the latter of whom recoup some of that lost profitability by keeping shelf prices relatively stable when raw milk prices decline – at least for a little while – and by bullying processors like Dean into accepting lower wholesale prices.

(these two charts show the same thing; just imagine them side-by-side to complete the time series)

Source: Dean Foods, IRI, USDA. Class I mover converted at 11.6 gallons per hundredweight.

They can do this (bully) because their concentrated bargaining strength, a function of significant consolidation since the mid-2000s,6 coincides with persistent excess capacity7 among a fragmented processing landscape. Dean has been exposed to a number of competitive bidding situations over the years and notably lost a significant regional private label in early 2013 that led to high-single-digit volume declines that year.

When raw milk prices abruptly inflect down, m.o.m’s will, at first, step-function up for a few quarters before normalizing to lower levels as retailers pass-through the lower prices. During times when raw milk prices and end demand are stable and there’s plenty of margin to go around, retailers blithely cooperate with processors; but when m.o.m’s are meager and demand is particularly weak, things can get ugly. Dean’s disadvantaged place in the dairy chain was laid bare in 2h09-2011, when, in light of tepid consumer demand, retailers ruthlessly cut milk prices to drive traffic and processors were made to increasingly absorb a disproportionate amount of the m.o.m hit. To make matters worse, retailers cut private label prices, stealing market share from Dean’s higher margin branded products. Unit gross profit spread was maintained in 2009 only because of raw milk and resin prices (the latter used in bottling) collapsed.

Source: IRI, USDA. Class I mover converted at 11.6 gallons per cwt

And after assurances that retailers had forsaken their margin-eroding ways, that the dairy ecosystem had achieved benign stasis, as there may be budding signs of unraveling discipline from both retailers – instantiated in compressing margin over milk even in this environment of rapidly declining dairy prices:

“the margin over milk decreased from $1.54 per gallon in Q3 to $1.48 per gallon in Q4. December’s margin over milk exit rate was $1.44, nearly $0.09 down from September’s margin over milk. This reflects the low point in 2015 as retailers’ compressed margins despite the relatively flat cost of raw milk. We recognize these levels of margin over milk have not been seen since 2014; however, we do not believe this is indicative of material pricing tensions within the marketplace.”8 - Gregg Tanner, CEO; Dean Foods 4Q15 Earnings Conference Call, 2/22/16

– and processor peers, who are increasingly competing on price:

“After stabilizing in the first three quarters of 2015, we saw a modest decline in our Q4 share, sequentially down 50 basis points from 35.2% to 34.7%. This share change was driven mostly by the loss of large format private label volume concentrated among a few customers predominantly in one region where significant milk over-supply has led to more aggressive pricing by processors and cooperatives.” - Gregg Tanner, CEO; Dean Foods 4Q15 Earnings Conference Call, 2/22/16

(How many isolated pockets of aggressive regional competition, RFP and retailer vertical integration volume losses have to be strung together before you stop pro-forming comps?)

Meanwhile, as retailers have passed through lower raw milk pricing, Dean has been forced to concede brand premium. The price gap between Dean branded and private label has narrowed from $0.77 per gallon several quarters ago to $0.71 more recently,9 which, in light of operating profits of ~< $0.10 per gallon, is a rather significant reduction. In the past, management has guided to ~$0.60/gallon as a stable long-term branded/private-label gap, suggesting significantly more downside.

But I suppose it’s also possible that Dean’s brand premium deviates from historical averages as it increasingly invests in brand, and maybe price discipline partly explains why Dean’s market share has fallen from 38% to just under 35% over the last several years. But, Dean’s branded mix has barely budged at just 35% of volume (at the low end of its historical 35%-38% range) and its cost structure is re-inflating on marketing investments and windfall profit based incentive comp.

Importantly, because of Dean’s extensive fixed manufacturing and distribution base, the merits of maintaining price discipline to protect its brands’ contribution margins seem largely nullified by fixed cost deleveraging on lost volume.10 And while Dean has closed distribution facilities to meet lower demand, it has endured higher “distribution penalties” – increased driven miles as coverage territory declines – as a result. So while management has commendably rationalized its footprint and reduced absolute dollar expenses over time (management has reduced operating expenses by $160mn over the last 7 years), its efforts haven’t outpaced volume declines:

And that’s why, despite generating slightly higher gross profit/gallon versus 2009, EBIT/gallon is substantially lower:

Earnings Adjustments

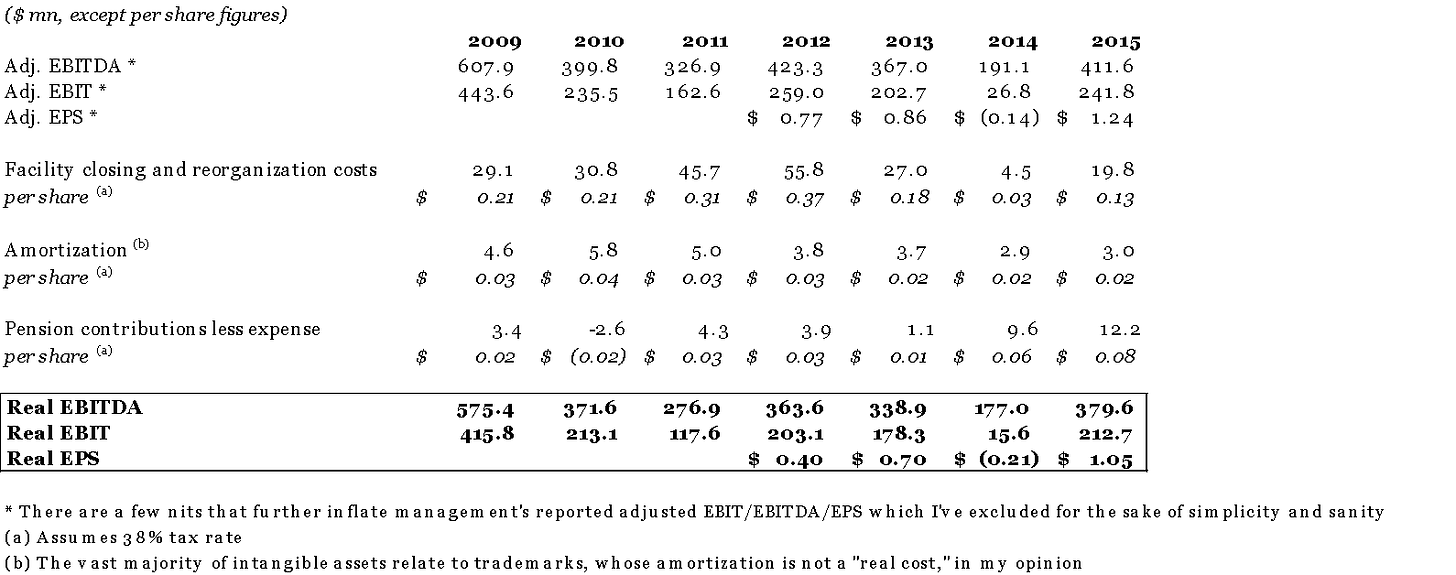

Management has charitably granted itself reprieve from all manner of recurring restructuring and reorganization costs, offering shareholders a misleadingly roseate view of earnings power.

These “facility closing and reorganization” costs incurred by the Company over the last dozen years average ~$30mn per year ($0.20 after-tax per current diluted shares) and have occurred every single year, yet are excluded from management’s adjusted EPS. These costs do not include the $158mn of litigation settlements or the $2bn in asset write-downs that have taken place since 2009.

I adjust management’s adjusted numbers to arrive at a truer reflection of earnings:

LTM valuation on my numbers looks like this:

Here’s one reasonable normalized valuation scenario:

Volumes decline, say, another 2% to 2.58 billion gallons per year.

Gross profit per gallon mean reverts to ~$0.70. In contrast to recent history, management’s cost cuts keep pace with volume declines, and opex ex. amortization/gallon plateaus to ~$0.63.

Then, EBITA / gallon of $0.07 x 2.58 billion gallons = ~$180mn EBITA. (I object to adding back the “D” since this industry has proven to be incredibly capital intensive over time).

Interest expense = $65mn

(Note: I am ignoring pension contributions, which seem to be running ahead of pension expenses in recent years and the $30mn or so in recurring facility closing and reorganization expenses).

EBT: $180mn - $65mn = $115mn

Taxed at 38% yields: $72mn in after-tax earnings, or $0.78/share.

Pick an earnings multiple for a company whose returns on capital average high-single-digits over time. 15x? So, call it 12 bucks.

$180mn EBITA yields $112mn NOPAT. I calculate total capital (shareholders’ equity + debt - cash) of $1.3bn and tangible capital (current assets – current liabilities + PP&E, net) of $1.5bn, translating into ~7%-8% returns, which feels about right for a commodity processor.

Another way to think about this is to consider that a year ago, the Company issued unsecured senior notes yielding 6.5% at par, which is what the equity – on peak gross profit / gallon, declining volumes and management’s ex-items opex – currently yields.

Appendix

For a simple business, Dean’s corporate history is rather intricate. What began as an aggressive levered roll-up story sputtered into a penitent de-levering one, as increasingly competitive challenges and tepid consumer demand have prompted perennial restructuring goals, cost-savings initiatives, management changes, and organizational realignments that have, at best, allowed Dean’s core dairy business to avoid perilously compromising its profitability over time.

The Company was on its way to hegemony in the packaged ice manufacturing and distribution industry11 through an aggressive levered roll-up strategy during the late ‘80s/early ‘90s when, in December 1993, it entered the dairy business through the acquisition of a regional dairy processor in Puerto Rico. It implemented its levered platform playbook again and IPO’ed as an ice and dairy corporate concoction in April 1996. A year or so later, the Company stumbled into the packaging business via a related dairy acquisition and rolled-up some of those too, but by summer 2000, Dean jettisoned both the legacy packaged ice business and its US and European plastic packaging operations,12 leaving it free to roll-up a fragmented, over-supplied dairy processing landscape,13 extracting savings from purchasing power and operating cost efficiencies along the way.

Dean is a shameless enabler of adjusted financials metrics. One-time costs related to plant closings, integration, cost reduction programs and various write-downs have hit the P&L, no kidding, just about every year since its IPO 20 years ago.

Dean has around 35% market share and is ~4x the size of the next largest processor.

When raw milk processed as fluid milk, it is purchased by processors at a regulated minimum price known as the Class I price and when processed into fattier, viscous goop or solids/semi-solids is purchased at the regulated Class II price.

The federal government’s minimum prices are determined monthly by an economic formula that takes into account supply/demand conditions and the processor’s geographic area.

not just raw milk prices but also the dramatically lower cost of resin in its bottles. There’s diesel too….well, maybe. So, years ago, when gas prices were ascending, management used to unequivocally site rising fuel costs as a clear headwind to profitability. But, over the last year, as fuel prices have collapsed, it now claims that fuel movements are mostly offset by revenue surcharges, yielding little to no benefit. In any case, the Company also struck diesel costs a higher prices and so has is not benefiting much from lower spot prices.

Significant grocery chain merger closings and announcements in recent years include: Ahold (Stop & Shop, Giant chains)/Delhaize (Food Lion, Hannaford), Cerberus/Albertsons/Safeway, Cerberus/Jewel-Osco, Kroger/Harris Teeter.

“…when I think about what we’ve done in taking 10% to 15% of our capacity out, and I think we’ve seen a little more de-leverage with the volume doing what it’s done and what we had expected, so we’re probably looking at somewhere in the low 60s. And again it’s so dependent upon different regions of the country and we’re have locations or not because there are certain locations that we have that are going to have considerably lower than that from the utilization perspective, obvious states like Montana, where we might be in the 30-40% type utilization, but we don’t see an opportunity necessarily to consolidate in that area. And then there’s other parts of the country where we’ll see it up in the 75% to 80% range, which is a range with fresh product where we would like to see it be.” - Gregg Tanner, CEO, 4Q14 Earnings Conference Call (2/10/15)

Take Gregg’s opinions with a generous grain. Had you taken the other side of his numerous price/competitive predictions over the years, you’d be flush.

In the past, management has guided to ~$0.60/gallon as being a stable long-term branded/private-label gap. Dean’s branded mix has ranged anywhere from 35% to 38% and tends to be at the higher end during periods of lower dairy prices, when the spread above private label doesn’t push the retail sticker price of branded milk to prohibitive levels.

Potential risk factor (if you’re short): For years, management has talked about distributing third party product to better leverage its significant refrigerated distribution system, though it has never quantified the potential opportunity.

That is, cocktail ice in 8 lb bags, sold primarily to convenience and grocery stores.

In July 1999, Dean sold the U.S. plastic packaging operations to Consolidated Container Company in exchange for cash and a 43% interest in Consolidated.

An outgrowth of more efficient manufacturing and the development of in-house manufacturing by large grocers, coupled with waning demand for fresh milk.