[FNF, FAF] Title Insurance, Ownership, and “Blockchain”

For real estate markets to properly function, the buyer of a property and the lender financing its purchase must be assured that the person selling it actually has the right to do so and that the delinquencies of any prior owner have not lingered in the form of present day ownership conflicts. In the US, that assurance is provided by a title insurer. A title policy is required by lenders and issued every time a house is purchased or refinanced, with fees from the latter averaging less than half of what is realized in the former. To affirm title ownership and validate what’s shown on the public record, the insurer undertakes a thorough due diligence process – combing through tax and court records, legal documents, maps, historical data on the property, prior title policies, federal tax liens, divorce proceedings, and other sources that may reveal undisclosed encumbrance – that traces the property title back through all previous owners. These documents, strewn throughout court houses, treasurer offices, and deed recorders across various state counties, are copied and aggregated by the insurer in regularly updated databases called “title plants”, which serve as the primary fount of information for future searches.

Based on this diligence, a report is furnished and circulated to all relevant parties and specific issues are remedied before the escrow agent – the party holding the funds related to the exchange of property ownership, often played by the title insurer – closes the transaction, typically within 2 months from the time the buyer’s offer is accepted by the seller. As remuneration for taking on this tedious task and assuming the risk that an overlapping claim went unidentified during diligence, the title insurer collects an upfront, lump-sum fee amounting to ~0.5% of the home value, collectively amounting to ~$17bn in the United States. While a typical P&C policy protects beneficiaries against future claims, a title insurance policy protects against past, unreported defects that were not identified as such until after property ownership was transferred. So, a title insurer’s ability to avoid losses is commensurate to the scope of its diligence [around 1/3 of title searches unearth a title defect and 30% of all title insurance losses are fraud related]. At ~5% of premiums, claims payouts are vastly outweighed by the 85% of premiums dedicated to reviewing titles, maintaining title plants, investing in technology, and curing defects [by contrast, a typical P&C underwriter might report an 80% loss ratio and a 20% expense ratio], though like other participants in the financial ecosystem, title insurers got swept up in the furor of the early 2000s’ residential housing bubble and endured claims costs that ran at a ~double digit percentage of premiums in the ensuing crisis (vs. a more typical provision of 5%-7%). Most claims are a result of fraud and paid out within 5 years, so the vast preponderance of bad deals from the pre-2009 vintages have been settled, and since then the industry has strengthened its fraud identification processes.

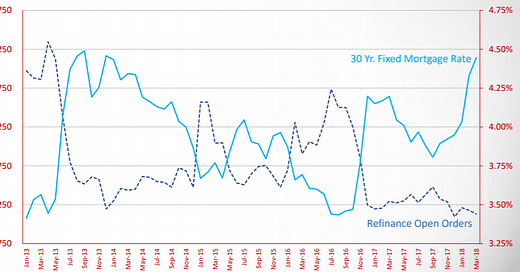

Premium dollars are pegged to housing turnover and transaction prices, and so ebb and flow according to three cycles: residential purchases, residential refinancings, and commercial real estate transactions. Rising rates weigh on housing affordability, which you’d think would crimp purchase volumes, but this intuition has not come to pass, with purchase volumes continuing to grow at lsd/msd pace. Refi volumes, on the other hand, have indeed been as highly sensitive to rates as you might expect. However, both FAF and FNF have seen growing profit dollars and expanding margins as healthy residential purchase and commercial volumes, growing interest income, and rising real estate prices all around, have more than offset the stunning collapse in margin refi volumes.

FAF’s refi open orders vs. 30 yr fixed mortgage rates:

Commercial real estate is a different animal. Volumes are lumpier and their 7-10 year mortgage terms are shorter, so they aren’t nearly as sensitive to refinancings. The discrepancy in fees between a commercial refi and residential purchase (~70%-80%) is not as vast as it is in residential (~50%), and because the fees per file are significantly higher – $8,000 for commercial vs. ~$2,000 for residential purchase – and the resources required to diligence them are not much greater, commercial pre-tax margins are ~twice as high. The industry consensus seems to be that origination volumes, which at $1.2tn are still below normalized levels of ~$1.5tn, still have room to expand; persistent housing shortages will continue to buoy prices, with FAF seeing housing shortages in 80% of its markets and just 3 months of inventory nationwide vs. more normal levels of 5-6 months); commercial real estate fundamentals are healthy; and refi volumes are trundling along at levels so low that they are biased to move higher.

Here is a financial snapshot of the top 4 national title players, who combined have 80% share of industry premiums.

…and below is data that I grabbed from the American Land Title Association (ALTA), which shows the number of states where each company has #1, #2, or #3 market share (You can find more granular state market share for the top 3 underwriters here).

Stewart (STC) is a story of woe – litigation expenses, severance charges from cost containment programs, goodwill impairments, and volume declines across not only refi volumes but also purchase and commercial (two areas where peers have been growing) – that finally appears to have reached its denouement with the March 2018 announcement that Fidelity National Financial would be acquiring it for $1.2bn ($50/share, half cash / half stock), which works out to around 5x fully synergized EBITDA after baking in some estimated revenue divestitures. FNF’s own stock is valued at ~8.5x EBITDA. While one might argue that the distraction of dealing with activist hedge funds1 who have been circling Stewart for the last 5 years – citing conflicts of interest among family members and lagging financial performance as ammunition to push for board seats, cost cuts, buybacks, and a sale of the company – were partly to blame for Stewart’s underperformance, in truth, the company has long been a laggard and needed a kick in the ass. Since at least 2015, Stewart has been touting 10% pre-tax margins in a “normalized” origination market, but this ambition seems ever more fantastical with every passing year that the origination market improves and its own margins go nowhere, even while FNF/FAF’s double-digit margins expand.

There’s been a lot going on at FNF over the last year. Last September, it spun-off its majority ownership of Black Knight, comprised mostly of the the mortgage data and analytics company formerly known as LPS, which FNF acquired in January 2014 and whose value as a “tech” company was being obscured by a title insurance multiple. Several months after that, the company completed a split-off whereby the tracking shares of FNFV Ventures – a subsidiary holding investments in varous disparate companies, including restaurants, an employee benefits platform, a healthcare IT company – were exchanged for those of the now publicly listed entity holding the actual hard assets and operations of said disparate companies. Following these two transactions, FNF is now predominantly a title insurance business with some real estate brokerages and a few real estate technology assets (doc prep software, CRM).

Fidelity National does around $860mn in pre-tax profits. Assuming a 25% tax rate, we’re at $2.30 in per share earnings, so the stock now trades at 16x. The cost synergies on the Stewart deal are big, $135mn on ~$90mn baseline consolidated pre-tax profits, and basically bring Stewart’s title margins from 5% to 12%, a few points shy of FNF’s. Given the implied county-level share concentration and likely divestiture conditions required by the FTC, the deal will take a while to close (probably ~a year), but the cost synergies should start immediately thereafter. Assuming the upper end of revenue divestitures and full realization of cost synergies – with the eventual goal of bringing Stewart’s margins to FNF’s, as it has done in the past with Chicago Title, Alamo Title, Commonwealth Land, etc. – I think we’re looking at ~$2.70 in EPS if the acquisition closes, so the stock trades at less than 14x pro-forma. Either way, the stock doesn’t seem so expensively priced if you accept that we aren’t at cycle peak. I don’t have a strong view here. Skeptics might point out that title margins at both FAF and FNF are at or above prior peak levels in 2003/2004, but mortgage originations today are less than half of what they were then, so it seems there have been structural efficiency improvements at both companies over the last decade that make it somewhat suspect to claim we are at “peak profitability” based on where margins crested in the past.