Is Global Payments the next Adyen?

(no, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be a good stock)

AI-generated podcast conversation: Spotify, Apple

AI-generated summary: Global Payments’ $24bn acquisition of Worldpay is the latest installment in the long-running saga of merchant acquirers trying to scale their way out of obsolescence. Less than a year after publicly swearing off M&A, Global is now pursuing a mega-deal that may make strategic sense in a vacuum, but directly contradicts its own stated strategy. The deal creates a formidable global acquirer, but also drags the company back into a legacy playbook of scale-first, integration-later. The setup? Messy, cheap, and not without upside – if investors can stomach the distraction.

I.

Last April, Global Payments announced that it would be acquiring Worldpay and divesting the Issuer Processing business obtained through its 2019 merger with TSYS, dismantling one monstrosity to create another. On the other side of the table, buying the business that Global is selling and selling the business that Global is buying, is Fidelity National, who had acquired Worldpay in a mega-merger of its own, only to sell a majority stake to private equity five years later after the strategic merits of the deal proved elusive. Scarcely in the history of payments have so many bankers been paid such enormous fees for so little value creation.

One could have hardly imagined what Global Payments would eventually become when it was spun-off National Data Corp.1 in 2001. Back then, merchant acquirers distributed payment processing services through two primary channels: banks, who owned the merchant relationships, and Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs), which you can think of as outsourced sales agents, though sometimes they evolve into something resembling the merchant acquirers they represent (Shift4, for instance, began as an ISO that sold payment processing on behalf of TSYS but eventually developed its own POS software and processed its own payments). As an independent company, Global Payments rolled up both, acquiring the merchant acquiring units of banks in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, and purchasing ISOs who catered to small and mid-sized merchants here and abroad.

Then, software ate the world. Merchants who traditionally sourced card processing services through banks and ISOs increasingly did so through the software they used to manage their operations. No company embodied this seismic shift in channel strategy more than Stripe, who hid the complexity of payments acceptance behind a few lines of code that developers embedded in SaaS applications. Within this milieu, Global Payments was a fusty incumbent, out of step with the times. Tethered to legacy distribution models, it endured seven years of slowing growth, margin erosion, and anemic shareholder returns, culminating in the retirement of its long-time CEO Paul Garcia. But just before Paul stepped down in 2013, Global acquired Accelerated Payment Technologies, taking the first meaningful step toward what came to be known as “integrated payments”, where core payments processing is integrated with third party software (in APT’s case, software used by dentists, vets, pharmacies, and merchants across many other verticals).

Jeff Sloan, Paul’s successor, sprinted with the baton, shelling out ~$1bn on growthy, margin-accretive integrated payments providers and e-commerce gateways in the span of just a few years. To put distance between itself and the ever more commodified business of payments processing, management began saying stuff like: “We are not a processor, we are not a payments company, we are not an acquirer. We are a technology provider to these customers who need to have these types of integrated interactions with their consumers”.

But, if you have to declare something like that out loud, it probably isn’t true to the extent you’d like it to be. Integrated payments was an improvement over the bank and ISO-led distribution of yesteryear in that it piggy-backed on growing software adoption. Still, under this model, payments is not entirely one with the software. The merchant acquirer and the independent software vendor (ISV) are two distinct entities. Each strikes their separate agreement with the merchant, who can work with any of the acquirers the ISV integrates with.

By contrast, in Embedded Payments the ISV doubles as the payment provider. The central actors in this model are payment facilitators (or ”payfacs”) like Toast, Square, and Mindbody. Payfacs underwrite and onboard merchants under their own Merchant ID, which puts them on the hook for KYC and compliance violations, meaning if one of Square’s merchants vanishes without delivering products that were paid for or sells a product, like CBD oils, that runs afoul of card network rules, any resulting liability falls on Square. Whereas in an Integrated Payments setup a merchant signs two distinct agreements, one with with ISV for the software and another with the acquirer for payments processing, in Embedded Payments a merchant signs just one agreement, with the ISV, who in turn either processes payments themselves or, more commonly, strikes an agreement with a third party processor. So, a restaurant using Toast as its POS typically doesn’t know – nor does it need to know – that Worldpay is ultimately processing payments beneath the surface. Toast has an agreement with Worldpay; the restaurant does not.

Global Payments offers two related but distinct payfac-oriented services. In the first, as a white-label processor for the payfac, it routes payment authorization requests through the card networks and settles funds to the payfac’s account, steering clear of merchant underwriting risk. In the second, as a program facilitator (or “profac”), it assumes the full responsibilities of a payfac on behalf of software vendors and online marketplaces.

But why stop there? Why not climb still further up the value stack, owning not just the payments or merchant onboarding layer, but the software itself? In that spirit, in April 2016 Global Payments made its largest purchase to date, acquiring for $4.4bn (~13x post-synergy EBITDA) Heartland Payments, the 9th largest US processor by volume at the time, whose coverage included a significant presence in restaurants, retail, convenience stores, K-12 schools and colleges. In owning the POS software, onboarding, and core processing, along with a direct salesforce to reach merchants (Heartland’s founder was philosophically opposed to ISOs), Heartland was about as vertically integrated as it gets. Global then spent another $2.3bn to acquire three vertical SaaS vendors2, aiming to replace their merchants’ existing acquirer relationships, using discounted software rates as a lure – a strategy not dissimilar to Shift4’s approach of loss-leading with POS software and monetizing through payments (the astute reader will recognize that these SaaS vendors are not payfacs in that they require each underlying merchant to have their own merchant account).

From an enterprise value of just ~$3bn in 2012, Global spent $8bn on growthy forward-looking acquisitions, until by 2018 nearly half its revenue came from integrated payments, e-/omnichannel commerce, and vertical software, business lines that hadn’t existed prior to this transformative journey. In the heady days of the late-2010s, with the market gushing over software, management encouraged analysts to value the company on a sum-of-the-parts basis.

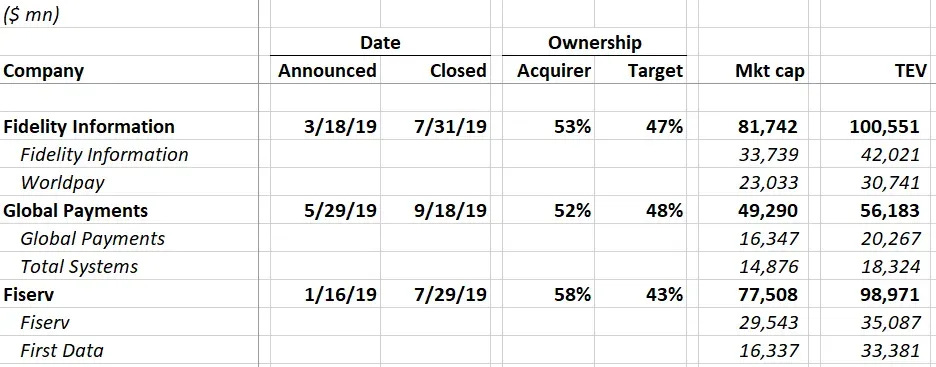

It was around this time when Global Payments and Total Systems (TSYS) smashed together in a humungous $56bn merger of equals, closely following the combinations of other legacy merchant acquiring/issuer processing peers:

To understand the logic motivating this merger, we first need to build up to what TSYS was about at the time.

TSYS traces its origins all the way back to the early ‘70s, when it was conceived as a mainframe-based transaction processing engine for Columbus Bank & Trust’s card program, a service that was then extended to other card issuing banks. In the decades after its partial spin off from CB&T in 1983, TSYS won ever larger, more complex portfolios and expanded internationally, eventually growing into one of the leading independent issuer processors. TSYS then expanded into merchant acquiring during the ‘90s, its first notable presence marked through a 50/50 joint venture with Visa, which it came to fully own a decade later. With its US issuer processing business slumping by 40% during the GFC on the collapse of two large clients, Wachovia and Washing Mutual, TSYS doubled down on the merchant side through a flurry of M&A3, so much so that by the time it merged with Global Payments in 2019, its Merchant Services segment nearly rivaled Issuer Processing by revenue.

Unlike TSYS and Global Payments, Worldpay didn’t evolve from a single corporate lineage but instead was born through combination of two: Vantiv and, um, Worldpay.

Vantiv was founded in 1970 as a subsidiary of Fifth Third Bank, focused on processing electronic funds transfers. In the early ‘90s, it pushed into merchant acquiring, establishing a strong presence among the top 100 US retailers. Desperate for capital in the fallout of the GFC, in 2009 Fifth Third sold 51% of Vantiv to Advent International, who then took it public three years later. Freed from Fifth Third’s constraints, the newly independent company struck merchant referral deals with banks it had once been barred from courting and, echoing Global Payments’ playbook, pivoted away from traditional bank and ISO channels. After it IPO’ed in 2012, Vantiv began buying its way into integrated payments and e-commerce, most notably with the $1.9bn acquisition of Mercury Payment Systems, which deepened Vantiv’s reach into the SMB market through POS software integrations.

Worldpay, established in 1989 as a subsidiary of NatWest, a UK bank, initially focused on merchant acquiring and payment gateways, before expanding into e-commerce transaction processing by the late ’90s. In 2000, Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) acquired NatWest, folding the latter’s merchant acquiring arm into its own and using the combined platform as a springboard for expansion. Over the next decade, RBS stitched together acquisitions and merchant acquiring partnerships across continental Europe, transforming Worldpay into one of the world’s largest payment processors. When the financial crisis crippled RBS’ balance sheet, the beleaguered bank was forced to divest non-core assets as a condition to receiving government aid. One of those assets was Worldpay, 80% of which was sold for £2bn to Advent International and Bain Capital, who took it public in 2015. In 2017, Worldpay merged with Vantiv in a $12bn transaction, with the combined entity retaining the Worldpay name.

So, Vantiv scaled integrated payments and card-present retail within the United States, tilting toward SMBs, while Worldpay delivered e‑commerce and cross‑border expertise, indexing toward global enterprises. Together they offered merchants an “omnichannel” platform spanning in‑store, online, and mobile payments acceptance almost anywhere in the Western world. A few years later, Worldpay itself was swept into an even larger deal, merging with FIS – a leading issuer processor with its own long, intricate history that I will not get into – to create a payments behemoth worth over $100bn.

II.

Phew. I mean, just an absolutely bewildering frenzy of acquisitions that go so many layers deep and encompass so many different processing engines across so many geographies that it comes as no surprise whatsoever that all attempts to consolidate them have utterly failed and long been abandoned. First Data tried for close to a decade before giving up. Vantiv eventually dropped the phrase “single platform” from its 10K. Adyen scanned at the mosh pit and rightly determined that the only way forward was to “start over again”.

But these issues were understood well before the crescendo of mammoth mergers in 2019. So, why’d they all go through with it? What was the point? There were the cost synergies, sure, which summed to 13% of combined EBITDA across all three mergers. But what strategic purpose did these transactions purport to serve?