IAC and MGM

There was a time, not too long ago, when an investor could treat IAC as a collection of binary early stage bets anchored by a few more mature and profitable entities. To most, IAC’s 12% passive minority stake in MGM, acquired near the COVID lows, was a weird one-off opportunistic gambit that could be marked to market. The real diligence was saved for Angi’s, DotDash, and Vimeo. I don’t think many felt compelled to deep dive into casinos because like, whatever, the $1bn MGM investment comprised just ~9% of IAC’s market cap at the time and it felt like most of the upside was going to come from IAC’s digital assets, not a passive minority stake in a mature brick-and-mortar casino operator. Psych!! Now Angi’s is melting away as its fixed price offering, launched to great fanfare 2-3 years ago, struggles to find product-market fit. DotDash no longer expects to hit its $450mn EBITDA target next year given the weakness in brand advertising. Vimeo has lost ~90% of its market cap since being spun off last May, as losses have widened, growth has dramatically decelerated off tough COVID comps, and investors have soured on unprofitable growth concepts. Meanwhile, MGM shares have nearly doubled from the ~$17 price at which IAC first accumulated shares in 2q and 3q 2020. IAC has since added to its MGM stake, first at $45 and more recently in the low-$30s. With valuations in digital growth assets wrecked and its own stock price sliced in half, IAC could have opportunistically acquired another digital lottery ticket or more aggressively repurchased (more of) their own shares. But no. They increased exposure to MGM instead. Today, the $2.1bn MGM position accounts for 35% of IAC’s market cap, making it the second most valuable asset in the IAC complex after DotDash.

MGM is a set of cash flowing retail casino properties plus a call option on a nascent but potentially massive online sports betting and iGaming opportunity through its 50% ownership of BetMGM. Through its Las Vegas Strip (LVS) segment, MGM operates 9 casino resorts, with Aria1, Bellagio, MGM Grand, Mandalay Bay, and The Cosmopolitan the most notable and profitable among them. The Regional segment consists of 8 casinos, with The Borgata (Atlantic City, NJ), MGM Grand Detroit (Detroit, MI), and MGM National Harbor (Prince George’s County, MD) contributing more than 60% of Regional’s pre-COVID segment EBITDA.

Las Vegas has come a long way from the mob-run cesspool portrayed in the 1995 classic Casino. In his concluding monologue, Sam Rothstein, head of the (fictitious) Tangiers casino, laments:

The town will never be the same. After the Tangiers, the big corporations took it all over. Today it looks like Disneyland….After the Teamsters got knocked out of the box, the corporations tore down practically every one of the old casinos. And where did the money come from to rebuild the pyramids? Junk bonds.

Today’s Las Vegas is an entertainment destination, host to an NFL team, dozens of industry trade shows, megastar concerts, and Michelin Star Restaurants. Profits have migrated away from low and mid-tier casinos like Circus Circus and Westward Ho, toward properties that resemble luxury cities, with high end retail spaces, restaurants, and other posh amenities enveloping conference attendees, high rollers, and Asian tourists, a favorable development for MGM and Wynn, whose Vegas portfolios tilt fancy.

Regional properties are more for the dead-eyed locals. Atlantic City and certain high-end 100k+ square foot casinos like MGM’s Borgata and National Harbor have a regional “destination” feel to them I suppose, but there are hundreds of others – like the Ameristar and Hollywood branded locations run by Penn Entertainment or the Isle of Capri and Harrah’s casinos run by El Dorado (now Caesar’s) – whose clientele is limited to middle-income gamblers in a ~100 mile radius.

So while MGM’s LV segment gets nearly 3/4 of revenue from non-gaming sources – hotel rooms, food, beverage, entertainment, and retail – close to 80% of Regional revenue comes from gaming.

You’ll notice a similar disparity at Wynn and, to a lesser degree, at Caesar’s, which latter operates shabbier Vegas properties like The Flamingo (will probably be sold soon), Bally’s, and Paris that don’t attract as much food and retail traffic.

The gaming industry has consolidated over time, with acquirers binding disparate casino properties together through loyalty programs, keep players engaged in an ecosystem. Through the MGM Rewards – the second largest gaming rewards program after Caesar’s, with ~35mn members – regional casinos can feed traffic to destination resorts, as the rewards earned by gambling at Beau Rivage can be redeemed for concerts or room discounts at the Bellagio or Aria.

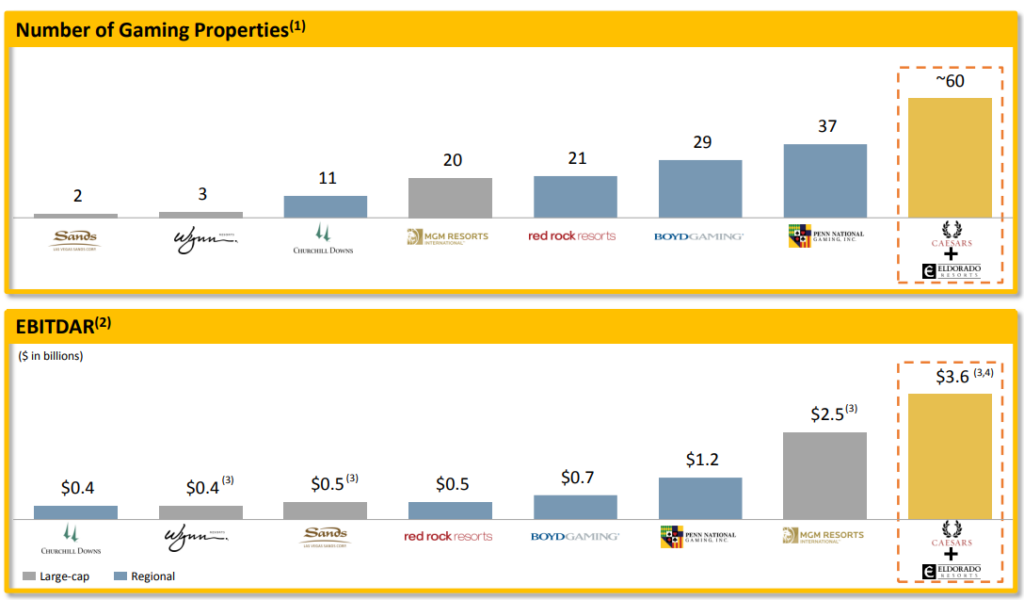

Here’s a pre-COVID summary of the top casino operators in the US:

MGM is in the middle of the pack in terms of property count, but generates the most EBITDAR per property with 3 of the 5 most profitable Vegas assets, and commands leading ~50% share of the Vegas gaming market, which is in a much better state today than it was heading into the last recession. Back then, Vegas was flooded with supply, with MGM, in partnership with Dubai World, breaking ground on City Center, an 18mn square foot hotel-casino-retail-residential colossus2 whose development costs exploded from $4bn to $9bn just as the economy tipped into recession. Exacerbating matters, another luxury casino resort, The Cosmopolitan, opened its doors just a year later in 2010. Since then, with the exception of Resorts World last year, there haven’t been any notable capacity additions and by most accounts there won’t be for at least the next 5 to 10 years. The returns just aren’t as compelling as they used to be. The Bellagio, the most profitable casino in Vegas, generated ~$500mn of EBITDAR at its pre-COVID peak on a development base of just over $2bn. If Resorts World is any guide, a comparable property would cost more than twice as much to develop today.

Following a brief COVID blip in 2020, Vegas is booming again. MGM’s LVS EBITDAR margins, at 38%, are 7-8 points above their pre-COVID peak on record revenue, even with cross-border travel restrictions deterring high-spending Asian gamblers and traffic from convention attendees, who are among the most profitable customers, ~1/3 below pre-COVID levels.

MGM isn’t alone. Caesar’s and Wynn have also reported record Vegas profits. Some of the margin gains are due to sustainable cost cutting and efficiency gains – things like self-service check-ins and the cessation of daytime entertainment and buffets and whatnot. But I think most of it can probably be attributed to temporary COVID spasms. Operators haven’t had to invest as much in promotions and marketing to lure pent-up demand and Average Daily Room rates are 36% above 2019 levels.

The Regional properties are also enjoying record margins but facing tough comps as locals apparently dumped their stimulus checks on slots and blackjack last year. But if the last recession was any guide, gaming revenue at regional properties tend to be relatively resilient.

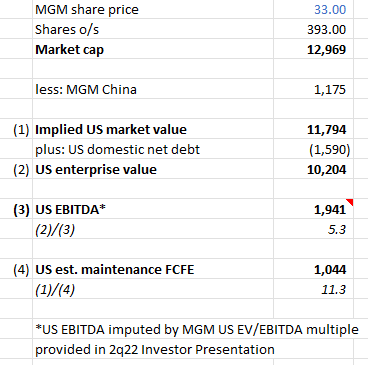

In addition to its US properties, MGM also owns a 56% stake in MGM China, which operates two casinos in Macau that derives ~80% of revenue from gaming. The Macau gaming market, once the world’s largest, has been decimated by draconian COVID restrictions that include occupancy limitations, temperature checks, quarantines for mainland Chinese residents. The Chinese and Hong Kong governments suspended group tour travel and ferry service. The consequences have been predictable. MGM China did -$66mn of EBITDAR over the last 12 months, down from $735mn in 2019. The Hong Kong listed stock has lost ~80% of its value since the start of 2018. With Macau and China lifting some restrictions in recent months, I’m inclined to think the worst has past. But even if I’m wrong MGM still looks pretty dang cheap:

And I guess MGM’s management thinks so too as they’ve raised capital through a series of transactions (see below), including the sale of the operations of The Mirage and Gold Strike for 17x and 11x EBITDA, respectively, to retire 31% of its shares since early 2021 at ~5.5x EBITDA.

(the most significant source of cash has come from the sale of MGM’s operating partnership units of MGM Growth Properties (MGP) – an umbrella partnership REIT that owned 7 of MGM’s LVS properties – to VICI Properties, another REIT formed in 2017 as part of Caesar’s bankruptcy restructuring, who is leasing back the properties to MGM. The real estate of MGM’s other 2 properties, Aria and Bellagio, is owned by Blackstone. Today, all of MGM’s domestic properties are owned by either VICI or Blackstone-affiliated entities. Sale-leasebacks have become a common way for casino operators to raise cash. El Dorado funded part of its $17bn merger with Caesar’s by selling casino real estate to VICI).

MGM’s profit margins are probably somewhat inflated and who knows if convention traffic ever reverts to pre-COVID levels. Compressing MGM’s property margins by 5 points and assuming no MGM China appreciation results in a valuation of 7.6x US EBITDA / 20x mFCF, which still seems reasonable for a collection of high-end casino resorts, bound together by a huge loyalty program, that gush cash as part of a consolidated industry structure. Admittedly, the US retail gaming industry is saturated, with few avenues for organic growth. But MGM has a few aces up its sleeve ;).

First, 15 years after it first actively explored development in Japan, MGM, together with its local JV partner ORIX, was finally selected by Osaka to build one of the country’s first integrated resorts. Several other US operators have tried to crack the Japanese market over the last 20 years, to no avail. Las Vegas Sands withdrew its bid in Osaka to pursue development in Tokyo or Yokohama before pulling out of those cities as well in May 2020. Wynn also dropped out of Osaka in 2019 after a decade of “working on Japan quietly behind the scenes”3. They claimed to be pursuing something in the Tokyo region, but haven’t followed up on this for years. Caesars withdrew from Japan following its merger with Eldorado, with Eldorado CEO Thomas Reeg cautioning analysts that they had “not made firm decisions on the international front”. But then soon after MGM won over Osaka, the company announced it was back in the game, working with Clairvest, former Las Vegas Sands executives, and a consortium of developers to build something in Wakayama.

Should the MGM-ORIX bid be approved by Japan’s central government sometime in the next few months, the consortium expects to break ground in late 2023 and open in 2029. This is a big deal. At an expected cost of $10bn, Osaka will quite possibly be the most expensive casino ever built. The project will likely be funded 50/50 between MGM and ORIX (or 40/40/20, with the 20% stub funded claimed by a yet-to-be-determined group of Japanese companies). Assuming its 50% share is 55% debt-funded, MGM will contribute around $2.25bn. I think the most expensive casino resort built so far in Asia is Wynn’s Marina Bay Sands (Singapore), which opened in 2010 at a cost of $5.8bn and did $1.7bn peak EBITDA on a $3bn revenue base. At 30% of gross gaming revenue (or “GGR”, amounts wagered minus amounts won by gamblers), Japan’s gaming tax rate is considerably higher than Singapore’s, which ranges between 8% and 22%. So maybe on a $10bn investment, the Osaka mega-resort delivers something like ~$6bn of revenue and ~$2bn of EBITDA. At 8x EBITDA, MGM’s 50% stake is worth $8bn, the equity portion ~$5bn, translating into ~$1.2bn of incremental equity value when discounted back 8 years at 12% (compared to MGM’s present ex. MGM China market cap of $12bn).

Possibly more significant is the latent value in MGM’s 50% ownership of BetMGM, an iGaming (online casino) and online sports betting joint venture with UK-based online gaming operator Entain4. Since the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) of 1992, which prohibited online gaming activity in most states, was overturned by the Supreme Court in May 2018, online sports betting has been legalized in 25 states. To the degree that Daily Fantasy Sports, which is regulated in 43 states, is a leading indicator for OSB we may see more states follow suit.

Online sports betting is now accessible to ~44% of the US population. Should Proposition 27 pass in California this November – which seems probable given that 58% of Californians supported the ballot measure, as reported by BetMGM management in May – penetration will ratchet to ~56%. This should be particularly good for BetMGM as Vegas traffic and MGM Reward’s membership over-indexes to California.

Without the cultural entrenchment of sports, iGaming acceptance has been harder to come by, legalized in just 7 states5.

Wynn tried to offload its OSB/iGaming division last year to a SPAC run by Bill Foley (of Fidelity National fame), but the deal was called off months later. At the moment, Wynn Interactive is run-rating at just $80mn in revenue (compared to $1.6bn of LTM revenue at DraftKings and $1.3bn of expected 2022 revenue at BetMGM) and isn’t losing nearly enough money to make me believe management is taking things all that seriously. Caesars claims around low-teens share of national sports betting measured by handle (the $ amount of wagers placed) but MGM has some exhibits that suggest Caesars’ share is much lower by GGR. PENN Entertainment, with $547mn of LTM digital revenue and its insistence on responsible growth, hasn’t engaged in promotional land grabs to nearly the same degree as peers, generating -$17mn of cumulative EBITDA on $889mn of revenue since the start of 2019 compared to -$2.9bn of EBITDA on $3.1bn of revenue at DraftKings. There are a dozen others getting after it but by most accounts FanDuel, DraftKings, and BetMGM are so far the primary contenders, with ~75%-80% combined GGR share in OSB and 70%+ share across OSB and iGaming.

Here is Online Sports Betting GGR share by state:

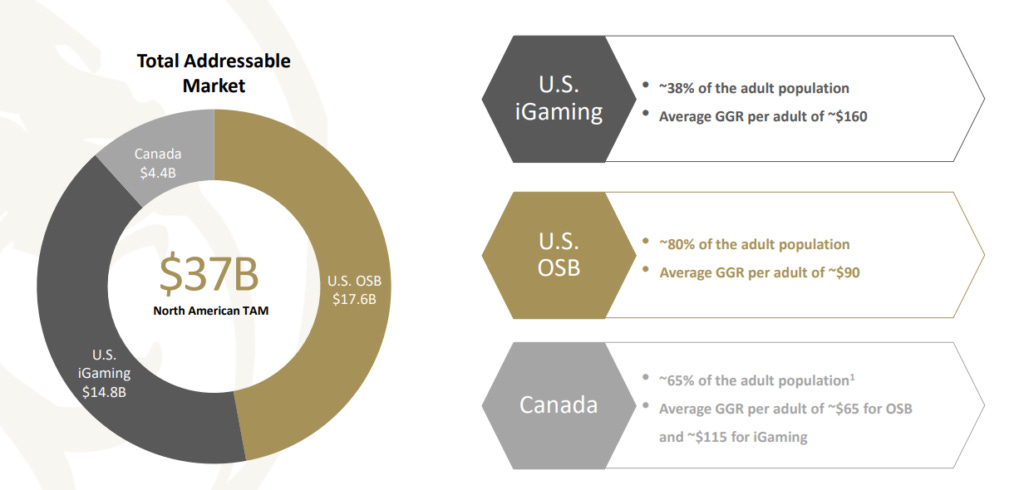

Just 4 years since PASPA was overturned, the $32bn addressable US market is fueling vertiginous growth for the leading participants. BetMGM is on pace to deliver $1.3bn of revenue this year, up from less than $200mn in 2020. FanDuel and Draftkings have likewise produced explosive triple digit annual growth.

(DraftKings estimates $26bn of US TAM by applying the OSB and iGaming gross revenue per adult in New Jersey, the most mature online gaming market, to the US adult population and adjusting for differences in per capita GDP).

The growth is not without controversy. The primary bear case is that in their rush to grab share, online operators are spending exorbitant sums on marketing and promotions that can’t be justified by the lifetime value of acquired gamblers. This past January, my friend Andrew Walker called attention to the frenzy of promotions in the newly authorized New York market, observing in his article What the fudge is happening with NY sports betting promos?

Seriously, the betting promos are absolutely bonkers. The headline craziness is Caesar’s / William Hill, which is giving away $300 in a free bet plus a deposit match up to $3k for a total of $3.3k in “free” money. FanDuel will give you $50 free plus a risk free $1,000 bet. DraftKings is doing a 20% deposit match plus a free bet that varies in size.

But I don’t understand how businesses can create positive value from the amount of free money that’s being given away. Consider Caesar’s, since they’re the outlier in terms of over quality. They’re givign away free bets; if you assume those bets are ~50/50, they’re effectively giving away $1.65k for a $3k deposit. Now, it’s not quite that bad, since you do need to do some betting to unlock all of that money, so Caesar’s will pick a little bit back in spread fees and everything…. but I just having trouble believing that the average customer Caesar’s is grabbing has a life time value of more than $1.65k.

With sales and marketing expenses more than double its gross profits, DraftKings has been burning cash hand over fist:

(check out the stock-based compensation running at 44% of revenue!)

These financials are a horror show.

DraftKings will retort that 83% of acquired customers retain after 1 year, 70% after 3; that a given cohort, including churned customers, generates 122% of year 1 revenue in the second year, 143% in the third. That doesn’t resolve the lifetime value question since those retention and gross revenue figures may be sustained by ongoing promotions. Also, that BetMGM sees most of its acquired customers churn off in the first 4 months before leveling off – a progression that seems more realistic to me – makes me skeptical of Draftkings’ claims (or at least its presentation of those claims).

BetMGM sometimes trots out this exhibit to demonstrate their strong competitive position across OSB and iGaming:

But what’s more interesting to me is how wildly market share shifts from month to month based on the relative promotional cadence of each participant. To be fair, a bunch of states have legalized gaming over the past year on a low starting base, so a player who gets the jump in a handful of new jurisdictions by bombing new gamblers with promotional offers can quickly find themselves taking meaningful national GGR share even if their competitors do a good job retaining existing customers. Even at a state level, a similar low base effect may be at play. In New York, Caesar’s Digital debuted this year with absurdly generous promotions (see Andrew’s post) to win 41% of GGR, only to see its share fall to 15%-20% as soon as it cut back on marketing. But given how nascent the New York OSB market is, Caesar’s may still find itself losing share even as it retains GGR from existing customers if most of the incremental GGR is picked off by competitors who continue carpet bombing the market with promos. Like let’s say in the first few months of launch, state GGR grows to $10 against an addressable potential GGR of $100, with Caesar’s claiming $4. Caesars can retain all $4 of GGR after it pulls back on marketing and still see its market share reduced to 20% if DraftKings and FanDuel promo their way to winning 80% of the next $13 of state GGR. In short, share volatility may be less indicative of an unhealthy market than an early one.

It’s worth noting that if customer retention sucks, GGR may be a misleading measure of sustainable share because it doesn’t subtract promotions, which latter can be so high that they comprise the bulk of GGR – for instance, in 1q22, Caesars Digital reported negative $53mn of net revenue (as Caesar’s admitted, ”we were more aggressive than we needed to be out of the box”). PENN Entertainment, who has excoriated its spendthrift peers, likes to point out that it has grown share on a Net Gaming Revenue (NGR) basis with a far more abstemious marketing diet.

But this is misleading in the opposite way because PENN’s NGR share will naturally grow in the short-term if everyone else is busy depleting their own NGRs with big upfront promos. And if acquired customers really do retain (and gamble) at high rates without much incremental marketing, then PENN will lose NGR share as state markets saturate and DraftKings, etc. taper off their splashy promos. Notably, since it dramatically curtailed CAC, pulling hundreds of millions that it planned to spend on marketing, Caesars claims that its national handle share has remained steady at around 15%, so maybe it’s had some success leveraging its loyalty program and physical properties to build loyalty with online gamblers.

To me, the most compelling sign that all this promotional spending may earn a return after all is that DraftKings is consistently seeing positive contribution profits (gross profits minus advertising expenses) in states 2 to 3 years after entry, suggesting that promotional costs do indeed taper off as as the number of remaining customers left to acquire shrinks…which of course would only be possible if existing customers didn’t need to be re-engaged at the same cost over and over again. In 2018, its first year in New Jersey, DraftKings reported $10mn of contribution losses on $21mn in revenue; in 2021, they generated $68mn of contribution profits on $239mn of revenue (28% margins). Between 2018 and 2019, DraftKing launched in 5 states. 4 of them were profitable by 2021 and the 5th is expected to be by the end of this year. The 2-3 year ramp to profitability has been observed by BetMGM and Caesar’s as well, with the former realizing contribution profits in just 6 months in Michigan.

So the idea is that digital operators have reported horrendous consolidated losses over the past year because the upfront losses from seeding new, legalized markets are overwhelming the contribution profits from the few, early launch markets of 2018 and 2019. With online gaming now available to most of the addressable US population, the profitability picture is poised to flip around this year and next as the contribution profits from current legalized states more than offsets promotional launch costs in the relatively few remaining states who haven’t yet authorized online gaming but will. BetMGM expects to be EBITDA profitable by the end this year; DraftKings and Fanduel towards the end of 2023 (though with SBC such a huge cost add-back for DraftKings, does it really count?). The precise path of margin improvement is confounded by the timing of new state launches – for instance, marketing and promotional costs from a California launch will absorb profits that would otherwise have been realized from existing states. But at maturity, digital operators expect to generate margins that are comparable to retail casinos.

For this to materialize, Tier 1 operators need to somehow acquire and engage customers in a cost advantaged way. As is true of any consumer facing app, engagement means having a responsive app with compelling content. Some operators might start by renting third-party gaming platform from Kambi or GAN. But to enable differentiated experiences, like variations of in-play betting and personalized gaming, all the majors have or are on their way to fully integrating their tech, with DraftKings acquiring SBTech, PENN Entertainment acquiring theScore as they transition off Kambi, FanDuel leveraging the tech platform of their parent company, Flutter, and BetMGM doing the same with their 50% owner, Entain. Everyone licenses content from IGT, Scientific Games, and Evolution through revenue share agreements but they also seem intent on pushing exclusive first-party games. As of April 2021, 5 of BetMGM’s top 10 titles were created in-house by Entain and Entain content accounted for 25% of BetMGM’s YTD GGR. PENN’s Barstool Casino gets 20% of its handle from in-house games, which it expects to grow to 50%. BetMGM estimates that in-house technology alone provides a 7% to 12% margin advantage over those who rely on third-party platforms.

The Tier 1s can also acquire gamblers at lower cost by piggy backing on existing assets. DraftKings and Fanduel converted their dominant share in daily fantasy sports into dominant share in online sports betting. PENN Entertainment hopes to lure the 20 to 40 year old audiences of popular sports media properties, spending more than $2bn for Barstool Sports and theScore. MGM and Caesars, with rewards programs that boast 35mn and 65mn members, respectively, can cross-promote across online and offline properties. BetMGM players enrolled in MGM Rewards and redeem points from their online play for discounted room rates or concert tickets or whatever at MGM’s regional or Vegas casinos. MGM reports that BetMGM is the largest source of new MGM Rewards enrollees, with over 43% of Rewards sign-ups now coming from BetMGM compared to 33% a year ago. Once ensnared in the MGM ecosystem, sports betters can be cross-sold iGaming and vice-versa. Where iGaming and OSB are allowed, MGM reported in 1q that 44% of online bettors engaged in both. Omni-channel players are acquired at just 30% of MGM’s average CPA and are predicted to be nearly twice as valuable as single-channel players. Finally, in states where they run physical casinos, MGM and Ceasars aren’t burdened with fees6 that pure online operators like DraftKings and Fanduel must pay to land-based operators in order to gain market access. BetMGM believes this provides a 6 to 7 point margin advantage.

Of course, none of these advantages prevent a newcomer from nuking the market with sloppy promos and destroying everyone’s unit economics for a while, though whether they can do so profitably without the scale of current Tier 1s is another matter. There is no reason for a gambler to download apps from no-name Tier 2 operators with no offline complements and inferior content and gameplay experiences, except to take advantage of one-time promos that are unlikely to prove sustainable. ESPN, rumored to be breaking into OSB, has the brand and audience to leapfrog into Tier 1 contention, but they will be starting years behind incumbents who have the tech, mindshare and, at least for MGM and Caesars, an irreplicable physical presence and rewards program. Plus, Disney is already burning billions on their DTC efforts. Do they want to burn billions more scaling OSB at a time when shareholders are whinging about cash flows?

Anyways, given the scale requirements this seems like the kind of market that will eventually consolidate around ~2-4 players. Whether they operate as a disciplined oligopoly is TBD, but at least for now, everyone is swearing off shock-and-awe marketing and committing to adjusted EBITDA profitability by next next year. Caesars is scaling back its cumulative digital EBITDA losses from $1.5bn to ~$1bn. For a while, DraftKings and Fanduel were granted permission to spend profligately while MGM and Caesars, whose shareholders were accustomed to free cash flow, were somewhat more constrained. But now even investors in hyper-growers are punishing growth at any cost (which comes with the silver lining that no new entrant will have the leeway that today’s iGaming incumbents have enjoyed the last 4 years).

Coincidently, DraftKings has guided to the same 30%-35% long-term EBITDA margin guidance that BetMGM has put out there, which doesn’t make much sense. Setting aside that DraftKing’s margin target is totally meaningless as it surely excludes massive stock-based comp, BetMGM has more efficient marketing thanks to its rewards program and doesn’t pay access fees in states where it operates physical casinos. And while DraftKings is already enjoying 28% contribution margins in New Jersey, the 13% gaming tax rate in that state is well below the average 19% sports-betting tax rate in the US. In New York, OSB operators are required to pay 51% of GGR for the first 10 years! DraftKings is also far more tilted to sports betting, whose mid-single digit percent of handle is well below the take rate on slots and table games, though tax rates on iGaming are higher than OSB and iGamers, according to MGM management, are also more expensive to acquire, so maybe it’s ultimately a wash.

Could OSB and iGaming cannibalize retail handle? Well so far, there’s no signs of this happening. Gaming revenue across regional and Las Vegas casinos is at or near record highs. In New Jersey, where iGaming was legalized in 2013, physical casino revenue has steadily grown and actually accelerated in 2019, the first full year of online sports betting.

Even if cannibalization eventually manifests, I think destination casinos like the kind MGM over-indexes to should be relatively more immune than mid-tier properties run by Caesars and PENN. We’ll see.

So look, I’m far from sold. But if the cohort contribution margins of the last 4 years are indicative of how market profitability evolves then iGaming/OSB looks like a call option that is getting more in the money with every passing quarter and, in my opinion, omni-channel operators like MGM and Caesars, with their rewards programs and offline complements, are best positioned to capture the spoils. BetMGM thinks that “long-term” (let’s call it 5 years) it can acquire 20%-25% the US market (conservatively pegged at 38% of the adult population as it excludes California and Florida), at EBITDA margins of over 30%. DraftKings thinks it can do $2.1bn of adjusted EBITDA on net revenue of ~$7bn (assuming 64% population penetration for OSB and iGaming in Canada and 65% and 30% penetration in US OSB and iGaming, respectively, compared to 46% and 13% today). MGM’s share and margin estimates get you to around the same place. So $2bn EBITDA at 10x, discounted back 5 years at 12% would mean that MGM’s 50% stake in BetMGM is worth around $5.7bn today, or about half of MGM’s US market cap. Or the whole thing could be shut down as the economics prove unsustainable. With MGM shares priced at 11x maintenance free cash flow, I don’t think the call option is priced in.

Stepping back, a conservative IAC sum-of-the-parts looks something like this:

MGM is cheap for all the reasons discussed. BetMGM and the Japanese venture, should they pan out, adds another ~$1bn of value to IAC in present value terms. MGM China is operating at trough profitability due to draconian zero COVID measures that will be eventually be relaxed.

Angi’s has been a big disappointment so far. I got this one wrong. The plain speaking optimism that I once found refreshing has now gotten annoying as it fails to be backed up by the financials. “It’s still early days”, but 2-3 years into the fixed price BHAG, we should at least be getting disclosures on the unit economics of the most mature service categories. Instead, the only profitability guidance we’ve gotten, besides vague and inconsistent qualitative color on contribution profits, is that gross margins across Angi Services are between 15% and 35%, a range so wide as to be meaningless. If product snugly fit market, I feel like Services would be growing at least 50% y/y organically at this early stage. Instead, the business is now growing low-teens, more like ~30%+ when you back out roofing, where they “just got ahead of ourselves in aggressiveness on price and some other operational challenges”.

I fear Angi’s challenges aren’t just temporary. The combination of Handy, a growth oriented “tech” company run by 20-30 year-olds in New York and HomeAdvisor, a more old-fashioned smile-and-dial outfit based in Denver, has resolved into cultural tensions. Feedback from contractors, who often don’t understand or appreciate the ROI math of Angi leads, ranges from “meh” to “bleh”. I have yet to encounter a contractor who thinks of Angi’s as a critical, must-have lead gen channel. Angi’s employees seem to have a short-term, mercenary bent, with a former Handy Sr. Director of Operations and Strategy commenting (h/t Stream Mosaic):

the attrition rate is very high, because of that, you need to bring in a lot of people. Like my example earlier, if you hire 100 people, you might be lucky if five of them make an entire year. I was in a training class of around 30 people, and by month four or month five or maybe month six, I was the only person in my training class left. Because it’s such a high attrition rate, you’ve got to really fill the top of your funnel of employees. You’ve got to fill it to the maximum. It’s very easy to get hired once you apply. There is not a lot of requirements, they’re not very stringent.

While Angi’s might provide reliable service in a dense city like New York (Handy’s HQ), at least here in Portland, OR, I literally it easier to find contractors on Google than I do on Angi’s. In short, I just don’t get the sense that people love working for Angi’s or that the service is particularly compelling to either service providers or consumers.

DotDash is no longer expected to hit $450mn of EBITDA next year due to a “rapid pullback” in ad spend from Retail, CPG, and Food verticals, but I’m still constructive on the long-term story. You’ll recall that last December, DotDash acquired the publishing division of Meredith with the idea of applying its expertise running fast, clean websites to Meredith’s storied brands, which include Southern Living, Better Homes & Gardens, and Martha Stewart Living (consider that Better Homes & Gardens is searched 11x more frequently than DotDash’s analogous home-focused property, The Spruce, yet gets just half as much online traffic). In 1q, Health.com was the first Meredith property to migrate to DotDash’s platform. With 30% fewer ads and 5x the site speed, click through rates increased by 60%, programmatic ad rates by 50%. Since then, 6 more properties have transitioned, with similar site speed gains. I am valuing DD/Meredith at 11x this year’s EBITDA, arguably too conservative for an asset growing revenue 15%-20% with minimal capex requirements and 50%-60% incremental margins.

Most of the remaining IAC is a collection of unprofitable, binary VC-type bets that nobody wants in today’s cash flow sensitive market environment. But IAC’s valuation is so bombed out that you can mark it all zero. MGM, DotDash, and Angi’s alone more than cover the enterprise value after subtracting the value of corporate overhead. Or you can put a zero on ANGI, as the sum of the remaining parts, marked conservatively, also cover IAC’s valuation.

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, accounts managed by Compound Insight LLC owned shares of IAC. This may have changed at any time since. [Update: as of 2/21/23, accounts managed by Compound Insight LLC no longer owned IAC shares]

acquired in Sept ‘21 through the acquisition of Infinity World’s 50% stake in CityCente

includes Aria, Vdara, Crystals, the Mandarin Oriental, and residential properties

CEO Matthew Ode Maddox; 3q19 earnings call

MGM tried and failed to buy all of Entain in 2021

Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and West Virginia

ranging between 5% and 15% of net gaming revenue