Related posts

Over the last 4 decades, a growing share of the pharmaceutical market has shifted from small molecules derived through chemical reactions to large molecules extracted from living cells1. The latter process is far more difficult. Cell populations are temperamental. They need to be fed with just the right amount of nutrients under exacting environmental conditions to reliably produce proteins of interest at large scale. Because of their variable nature, biologics are produced under more rigorous quality control procedures. Whereas a small molecule drug might need to pass through 40 to 50 critical tests, a biologic is subject to more than 2502. The facilities dedicated to bioproduction are also far more expensive and time consuming to build than those purposed for small molecules.

Over the last 4 decades, as drugs have from small molecules derived through chemical reactions have given way to large molecules extracted from living cells (biologics) – enzymes, antibodies, and other proteins harvested from mammalian cells, commonly Chinese hamster ovaries (CHOs) – the process of manufacturing them has gotten more complex.

Even as drug manufacturing has gotten more complicated and capital intensive, the R&D breakthroughs feeding the pipeline are increasingly conceived by emerging biotechs, who develop the protein or gene of interest but don’t have the plant infrastructure to manufacture biologics at scale, let alone the expertise to scale up stable cell lines from a gene sequence or the know-how to stay compliant with the onerous requirements of current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs). In addition to applying technical expertise, a drug manufacturer must validate that the production process consistently generates the protein of interest; test the purity and potency of raw materials and the final product; and assiduously document the bill of materials, equipment, quality testing results and product yield of each batch, among other items, all of which is reviewed by the FDA. So emerging biopharmas (EBPs), these under-resourced havens of innovation, outsourced not just commercial manufacturing but also earlier stage development steps. CMOs became CDMOs.

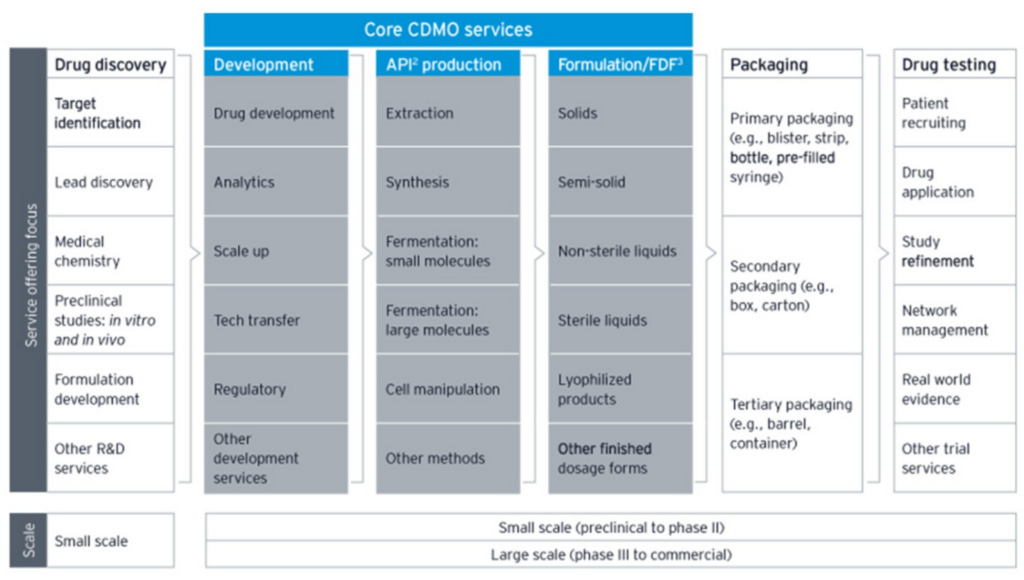

Here’s a helpful visual of the services that a large CDMO typically offers:

The middle column of the grey area, “API production” (or “drug substance” production), is the primary business activity of CDMOs. It refers to the production of active substances – proteins in the case of biologics or chemicals in the case of small molecule drugs – that produce the intended therapeutic outcome. This phase is buttressed on either side by: 1) “Development”, which includes scaling up viable cell cultures, validating potency, and complying with regulatory guidelines, among other steps that ensure drug substances can be created in a super rigorous and consistent way before commercial production begins and 2) “Formulation”, where the active substances are combined with inactive ingredients (”drug product”) and put into appropriate dosage forms, like capsules, creams, syringes, and tablets. The tail end of drug manufacturing, where the drug product is put into dosage forms and dosage forms are packaged into labeled bottles or syringes before being shipped out, is commonly referred to as “fill and finish” (for more details on the bioproduction process, see my Thermo Fisher post).

The major biologics CDMOs support customers across the development pipeline, with revenue dollars and duration increasing progressively as a drug moves from Phase 1 and 2 ($4mn-$6mn over 3 years) to Phase III ($20mn-$50mn over 3-5 years) to commercial manufacturing ($50mn-$100mn annually). Development contracts are profitable and worth winning in their own right, but they also feed into commercial manufacturing, where the big recurring bucks are made.

Most large pharma drug production is still done in house. Some sponsors will rely on CDMOs for swing capacity when their own facilities are booked for higher priority drugs or if there is a sudden burst of demand, as with the COVID vaccines.

But the share of new drug originations is shifting away from large sponsors to emerging biopharmas (<$500mn of revenue and <$200mn of R&D3), who now claim 67% of drugs in the R&D pipeline, up from ~35% 20 years ago, and have little choice but to outsource.

What’s more, EBPs were responsible for 69% of launches last year, up from less than 50% in 2013, meaning that rather than partnering with a large pharma, EBPs are bringing the drugs they discovered to market themselves. This is important because unlike established competitors, they never had to lay huge sums of capital to build their own manufacturing plants, just as no post-2015 software vendor had to buy their own servers. Moderna relied exclusively on CDMOs to manufacture its COVID-19 vaccine for clinical trials and launch.

Once the FDA has qualified a manufacturing process for a particular drug, including all the consumables and equipment that go into it, that process isn’t going anywhere (further upstream, this is also what makes the bioproduction consumables and instruments, sold by the likes of Danaher and Sartorius to pharma sponsors and CDMOs, so sticky and recurring). It doesn’t make sense for a sponsor to switch production to a competing CDMO offering a somewhat lower price since doing so would mean re-submitting a Biologics License Application and demonstrating to regulatory agencies that the drugs being produced in the new facility will be comparable to those produced in the existing one. It can take up to a year to mount regulatory hurdles and port the documented knowledge, procedures, quality parameters, and other items required to faithfully replicate the drug’s production (”technology transfer”) from one CDMO to another.

Moreover, while a sponsor looking to optimize cost and speed might outsource early phases to WuXi, they will usually transfer tech to Lonza (or some other CDMO with a reputation for scaling big volumes) at the mature phases of clinical trials, when reliability and scale really start to matter and regulators are paying close attention. At this point, the development pipeline is a reliable feeder into commercial production, since the further a drug has progressed through the pipeline, the harder it is to transfer tech…that is, a CDMO that handles production for Phase II or especially Phase III trials is very likely also going to handle commercial production when the NDA is approved.

One readily accessible analogy that comes to mind when thinking about the outsourcing trend in life sciences is semiconductors. Much as the semiconductor industry migrated from a vertically integrated setup to one where designers rely on TSMC and Samsung to manufacture their chips, so too are pharma sponsors unbundling Sales/R&D and manufacturing. But the industry structure for CDMOs is not nearly as favorable. For leading edge nodes, TSMC is basically the only game in town. Even giant semi designers like Nvidia and Qualcomm rely more or less exclusively on merchant fabs. The same is not true in pharma. Pfizer, GSK, and other large pharmas manufacture most drugs in their own manufacturing plants even as they outsource some production to CDMOs.

It looks like the global CDMO market was about $70bn in 2022, disaggregated like this (ballpark estimates!):