[RAMP – LiveRamp] Ad Tech Situations are Special

Earlier this month, Acxiom completed the sale of Acxiom Marketing Services (AMS), a segment that accounted for ~3/4 of its revenue and nearly all its segment profits, to Interpublic Group for $2.3bn. AMS partly helps manage the marketing operations of big brands – designing and maintaining customer databases, running custom performance analytics, aggregating third-party data1 and pairing it with first party records to construct comprehensive consumer profiles for purposes of launching marketing campaigns – as part of splashy, multi-year, multi-million dollar engagements that can take up to 9 months to set up. It is a business characterized by significant switching costs and minimal churn. But it is also a mature enterprise with declining organic growth, struggling to keep pace in an environment where consumer attention is fragmenting across channels, surplus is accruing to walled gardens like Google and Facebook, and marketers are adopting ever more sophisticated self-serve technology.

Now, unlike competitor Epsilon (owned by Alliance Data Systems), which has only recently relented on its long standing view that a high touch “end-to-end” managed service offering is just as relevant as ever, Acxiom began transitioning away from services and towards product and technology 5-6 years ago, most notably through its $310mn cash acquisition of onboarding provider (I’ll explain what that is later) LiveRamp in May 2014. Over the subsequent 4 years, Axciom jettisoned various non-core assets, including businesses involved in paper surveys and call centers in Europe, IT infrastructure management, and email marketing as part of an extended delousing journey that has now culminated in the aforementioned sale of AMS, leaving behind a profitable, rapidly growing SaaS entity. The Acxiom brand will be transferred to IPG as part of the sale and the residual company will be fittingly renamed LiveRamp.

After subtracting taxes and transaction costs, net sale proceeds amount to $1.7bn, $500mn of which will be used to tender for its common stock, resulting in a pro-forma market cap of $3bn and an enterprise value of just under $2bn. So the stock trades at 8x its run-rate revenue of $236mn, which, statistically speaking, is cheap relative to other 30%+ SaaS growers with 110% net dollar retention rates. And unlike many fast growing SaaS peers, LiveRamp is actually EBITDA profitable (after stock comp) and showing significant margin expansion (19% LTM EBITDA margins vs. 4% in fy16) to boot.

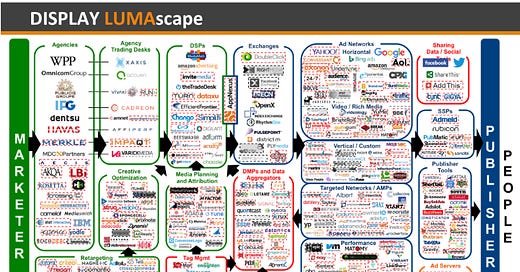

The mechanics of ad tech are pretty damned complicated and I won’t give it the full treatment (I couldn’t, even if I wanted to), but I need to at least explain the basics.

When you walk into a Nordstrom and purchase a bow tie, the details of that transaction will be stored in a database alongside the phone number, email address, and home address that you provided when you signed up for Nordstrom’s loyalty program. In any given day, you might be perusing Tech Crunch on your iPhone, logging into the Wall Street Journal from your work PC, checking Facebook on your iPad, offering up opportunities for Nordstrom to present you an ad for, say, cuff links to go along with that bow tie. But how does Nordstrom (or the agency it is working with), associate you, the physical person who walked into the store, with you, the person browsing websites across various devices?

We need to somehow link two identities: the physical you and the anonymized digital you. John Smith and Anon123. If we lived in a PC-only world, we might rely on cookies to establish your online identity. A cookie is a snippet of text that a web server stores on your hard drive that allows a website operator to store data related to each visitor and access that data later. There are two types of cookies, first party and third party. Let’s start with first party. When you visit amazon.com, Amazon will drop a cookie file on your PC that contains a unique user ID. Tied to that ID will be your username/password, shopping cart items, and data related to other site preferences and activities, all of which are store in Amazon’s database alongside that ID2. Every time you visit Amazon’s site thereafter, your browser will retrieve that cookie file sitting on your computer and send it to Amazon’s servers along with the page request. Amazon will then deliver a website with all the preferences linked to that cookie ID.

These first party cookies, named so because the cookie is dropped by the website that you are purposefully visiting (in this case, amazon.com), make it easier to maneuver across the web. Thanks to first party cookies, you don’t have to punch in your login credentials every time you visit amazon.com or nytimes.com. Third party cookies, on the other hand, are text snippets dropped by an ad exchange like DoubleClick when you visit any site that serves ads bought and sold on DoubleClick. These cookies can track your behavior, including the products and ads you click on and the content you read (hence why third party cookies are often referred to as “trackers” or “tracking cookies”), and that information can be used to “retarget” ads to you across websites that serve DoubleClick ads. So if you click on a GQ article about about men’s winter fashion, you might find yourself looking at an ad for winter gloves when you visit Seeking Alpha (assuming both sites are part of DoubleClick’s publisher network)3. The DoubleClick ad exchange obviously doesn’t know who you, John Self, are but it can nonetheless link your web browsing to a unique cookie ID stored on your hard drive.

But in today’s connected world, consumer attention is not just relegated to PCs, where tracking cookies work reasonably well for ad targeting. Rather, it is dispersed over several different computing devices, presenting the challenge of tying each of those devices back to a single user4 so that ad performance can be measured and the same person isn’t bombarded with the same ad across multiple screens. In other words, there are two association problems. First, all your devices need to be paired to your digital persona (cross-device matching) and second, your digital persona needs to be matched to your physical self.