[Sirius/Pandora – SIRI; Spotify – SPOT] Long-term relevance, long-term dominance

Prior to their July 2008 merger, Sirius and XM were locked in a bloody Betamax/VHS-like standards war: each company operated its own satellite constellation and broadcasted on separate frequencies; each had its own radio to receive and digitize signals; each spent extravagant sums marketing their services and mirror imaging the other’s content – Sirius had Howard Stern, XM had Opie & Anthony; Sirius had the NFL, XM had Major League Baseball – knowing that the more quality content it had, the more listeners it could attract, and the more listeners it attracted, the more likely carmakers were to install its chipsets1. By taking the lead, a satellite provider could scale content costs over more users and bid more for quality content, attracting still more consumers and OEM adoption in a virtuous cycle that would drive the second-best competitor to extinction.

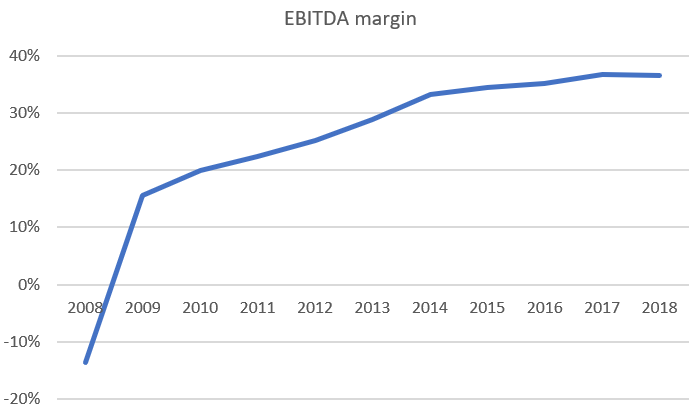

Sirius and XM together racked up $6bn in losses trying to tilt the market (back when billions of dollars in losses meant something). By merging, the companies could consolidate content (no need for two Country channels), rationalize spectrum, eliminate overhead and marketing, and command more bargaining power over content providers, who would no longer be positioned to play one off against the other. In its first full year, the combined entity, SiriusXM, realized what each company on its own never could: profits ($384mn in EBITDA), and at a time when new vehicle sales were still in the shitter. Margins have levitated higher ever since:

[It seems quaint to think that on a combined subscriber base of 14mn, this merger of equals was plagued by major anti-trust concerns (defining “satellite radio” as its own market seemed absurdly narrow, even at the time). Management was very careful to define its market as broadly as possible, to include 223m weekly AM/FM radio listeners, internet radio, cable audio services, iPods, mp3s, etc.]

But before it could get to this place, the combined company was in a fight for its life. The XM transaction closed in summer 2008, just as the economy was tipping into the credit vortex. By December, Sirius was a penny stock with $600mn in market cap and $3.2bn of debt obligations, its $4bn enterprise value a fraction of what it was in 2004 ($15bn). The market was pricing in bankruptcy, not because of operational challenges – the merger with XM had entrenched SiriusXM as the dominant satellite radio player and augured massive synergies and free cash flow generation. Revenues were still growing by double-digits and monthly churn, at less than 2%, barely budged – but because Sirius had too much debt coming due.

With the pressure of near term maturities mounting, Sirius accepted a two-part rescue financing deal from Liberty Media, who no doubt glimpsed the company’s fundamental strength through the turmoil: 1/ a $280mn senior secured loan bearing 15%(!) and 2/ a $150mn second lien loan accompanied by preferred stock convertible into 40% of Sirius’ common stock. In 2013, Liberty converted, and then bought more common shares, bringing its ownership of Sirius to greater than 50%. After years of buybacks, that equity stake grew to ~68% (after accounting for the shares that Sirius issued for Pandora). At the time of Liberty’s investment, Sirius was burning cash and its market cap was hovering around $500mn. Today, its $1.6bn of free cash flows supports a market cap of ~$27bn. Not bad, Liberty.

A few years after Sirius and XM obtained the radio spectrum required to get satellite radio off the ground, an entrepreneurial trio founded Pandora, hoping to revolutionize radio in a different way, not with satellites and terrestrial repeater networks but with internet infrastructure and data science. Sirius’ ability to personalize content based on engagement was limited by the fact that satellite broadcast was delivered through a one-way pipe. The best it could do was aggregate content along thematic categories like rap music, sports, news, and talk. The two-way internet pipes that carried Pandora’s content, on the other hand, could also return engagement data from the “thumbs up/down” assessments assigned to songs that algorithms iteratively curated for each listener. Its Music Genome Project – content programming algorithms informed by a database of 1.5mn songs (a subset of Pandora’s catalog), each individually evaluated across 450 attributes (tone, tempo, emotional intensity, etc.) by music analysts – delivered a “lean back” radio experience tailored to each listener’s unique tastes. Curation was a unique value add when Pandora launched nearly 20 years ago and the company’s user base grew rapidly, from 7mn monthly active users2 in January 2009 to 81mn by December 2015.

In its early days as a public company, skeptics maintained that Pandora would have a hard time expanding its gross margins, given the variability of its content costs. But this was never quite true in the sense that Pandora, for the most part, didn’t pay a flat percentage of revenue in content royalties. It instead paid a fixed fee per track (which management reports as licensing costs per thousand listener hours, or LPM, which is roughly the same thing as “per track” since the company caps the number of song skips)3. Those fees escalated every year, but they were basically fixed within a given increment of time. Leveraging content costs was therefore a matter of selling more ads at higher prices. Of course, it couldn’t pollute the listening experience by cramming in more and more ads, but compared to terrestrial radio broadcasts, who saturated the airwaves with 20-30 ads per hour, Pandora’s 6-7 ads left a lot of excess inventory to monetize.

Advertising seemed like a sensible monetization model at the time. In 2015, Pandora commanded more US streaming hours than any other music service. It had tons of data on listener preferences, data that it could use to intelligently match ads. And since those ads were triggered by a specific action, like song skipping, it could ensure that those ads were served to and seen by real people.

as of September 2015

Avg. mobile hours spent per user per month (December 2015)

But as healthy as Pandora may have looked in 2014, with gross margins reaching new highs and revenue growing by 40% over the prior year, its façade was cracking. Active user growth flattened the following year, then contracted two years after that. Listener hours and ad revenue followed the same trajectory, the former contracting and the latter plateauing in 2017. Pandora had always boasted that by gleaning personal preferences from its massive user base, it could deliver songs so hyper personalized that listeners didn’t have to go through the inconvenience of doing it themselves. But by 2015, with Spotify’s active user account surpassing Pandora’s for the first time after several years of superior growth, it was increasingly obvious that users, particularly millennials, preferred the agency and choice that Spotify offered – the ability to search for and listen to specific songs and artists, organize tracks into playlists, and share those playlists with friends. But still, Pandora’s management team was skeptical that people would pay for on-demand streaming. Informed by its experience with iTunes Radio, whose launch precipitated a 2% drop in Pandora users that reversed just months later, management believed that any share it was losing to Spotify could be attributed to free trials that would ultimately fail to convert.

It was wrong:

Pandora was caught in a bind. It was promising growth but boosting ad loads to offset MAU stagnation was a precarious move given the streaming competition that had come online (not just Spotify but also Apple Music, which launched in June 2015). And so, in 2016 Pandora began securing direct label deals and building a content and rights management system in preparation for its own on-demand service. It started offering services for musicians – analytics, marketing, direct publishing, all stuff that Spotify would later launch – and, through its acquisition of Ticketfly, leveraging listener data to intermediate sales of concert tickets. By late 2015, Pandora’s ad-funded internet radio business had broadened to a platform initiative that encompassed subscriptions, transactions, commerce, and event sponsorships that catered to artists, labels, concert venues, and listeners. Management huffed that these ambitious gambits busted open the boundaries of its $45bn US radio and digital marketing TAM, to encompass a $200bn “global music marketplace” (whatever that means). But really, this seemed more like a flailing attempt to try something, anything, to offset glaring share losses.