[TTD – The Trade Desk] A gorilla in ad tech?

Google and Facebook have come to dominate online advertising in the US, claiming 60% of the industry’s revenue. It’s easy to understand why. With billions of users persistently logged into their properties, Facebook and Google have broader reach than just about anyone in the ad ecosystem and can ensure that impressions are served to as many of the right people as possible. It’s not that advertisers want to rely on Google and Facebook (and soon, Amazon). It’s that these companies offer far better targeting than the shit stew of open web ad tech tools that rely on third-party cookies.

Amazon also has its own in-house tech, including a DSP, to run programmatic ads. Trade Desk’s management claims that because Amazon directly competes with so many large brand advertisers, the retail giant will face pushback from brands on objectivity grounds (you will almost never hear an ad tech management team fess up to bad news). I don’t see that happening. First-party log-in plus rich down-funnel purchase data is a formidable combination for advertisers. Amazon is claiming more of the industry’s growth than either Google or Facebook1, its share of industry revenue estimated at 9% this year, up from 7% a year ago. The company has further expanded its reach with its recent acquisition of Sizmek’s ad servers2. Amazon is looking like a significant concern that will further exacerbate the squeeze being put on ad tech.

But the web still needs a transparent intermediary with wide reach who is not obligated to sell against its own media properties and can act as an unconflicted agent for buyers to source the highest ROI inventory anywhere on the open web and on connected TVs. That’s the role that The Trade Desk is trying to play. Ad tech will continue to consolidate over the next decade…there are just too many participants and not enough surplus to go around. Along with Google, Adobe, Amazon, I think Trade Desk will be one of the few significant entities in the open web value chain.

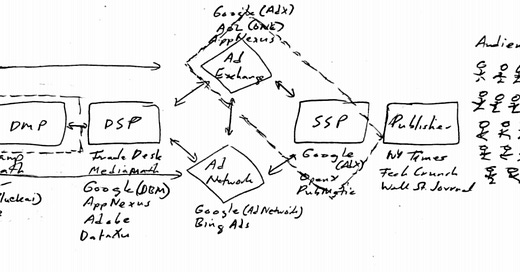

Below is an exhibit I used in a prior post. Thirty years ago, this flow diagram would have been compressed into three boxes: advertisers, agencies, and publishers. The explosion of online media, and the speed and flexibility with which ads can be placed against it, have birthed new middlemen competing for the profits that traditionally accrued to agencies, who in a simpler era handled many of the advertiser’s buying functions in-house. Historically, a marketer or agency would use websites as a proxy for the audience it wanted to reach, buying impressions on Guns and Ammo to reach men, aged 35-44 with incomes between $20k and $60k or on Cosmopolitan to reach women, 18-34, $50k-$90k, and re-allocating marketing budgets across different sites every few weeks based on campaign performance. With programmatic, an advertiser orients its campaign around potential customers rather than websites, leveraging data to more precisely tailor audience segments, deliver customized promotions, and optimize targeting according to budget and cost of customer acquisition constraints, automatically and in real time.

The way this works is a marketer will use a Demand Side Platform (DSP) like The Trade Desk to automate the process of buying ad inventory from publishers, who supply their available inventory through exchanges and Supply-Side platforms (SSPs). Through a DSP, the marketer can specify the location, device, demographic profile, language, browsing behavior, etc. of its target audience and block disreputable pages from bid consideration, specifications that it will often supplement with first or third-party data sourced from a Data Management Platform (DMP)3. The DSP then connects to various ad exchanges where, within a few milliseconds, it analyzes the inventory offered by publishers (via SSPs) and submits bids based on the criteria set by the advertiser or agency, who can, in real time, alter media and targeting based on the performance of on-going ad campaigns.

The first generation of DSPs took a “line-item” approach to structuring their bids, assigning a separate record to every permutation of as many relevant factors – like age, gender, ad size, location, time, region, country, etc. – as possible. So, “Female, Midwest, 11am, 300×250 pixels” got one row and “Male, Midwest, 11am, 200×200 pixels” got another, and so on, until, in theory, every possible impression was covered, with an optimal bid and budget assigned to each line. You can visualize this as a decision tree with end nodes encompassing every combination of factors. As you can imagine, at some point, the volume of records explodes to lengths exceeding practical memory constraints. And so DSPs necessarily restricted the number of line items and when evaluating inventory that wasn’t explicitly accounted for in the table, they interpolated a bid by shooting an arrow in the space between whatever records closely approximated the impression’s factor combinations, which resulted in suboptimal bidding.

Then The Trade Desk came along, and rather than put up an inflexible, monolithic database – an imperfect version of an unachievable ideal that averages out to mediocre bids – it isolated each constituent factor as its own independent variable, assigned relative weights within each of those factors (a 300×250 impression is worth this much more than a 320×100; a visitor in the Midwest is worth 1.5x more than one from the West Coast, etc.), and represented the bid as a linear function of those all those variables. “Bid factoring” dramatically alleviated the line-item method’s memory demands because we’re dealing with, say, 6 factors, not 720 (6x5x4x3x2x1) line items. Rather than reading off pre-cached bids and consuming scarce RAM, The Trade Desk calculated bids in real time with factor building blocks, taxing much more scalable CPU. This gave rise to faster feedback loops, a better trading engine, and a way of decomposing how much each factor contributed to a bid.

Basically, modularizing factors produces bids that are much closer, on average, to a hypothetical ideal price than working off a table:

Green line: ideal bid; blue line: factored bid; purple line: line-item bid. Source: The Trade Desk Corporate Analyst Meeting (3/6/2019)

The line-item method gets it ~exactly right on occasion but misses the mark by a wide margin most of the time. Bid factoring, meanwhile, misses more frequently but the sum of its misses is smaller. Notwithstanding iterative improvements in processing efficiency that has crescendoed to a system capable of handling 10mn queries per second, I’m not sure I’d point to bid factoring as the source of the company’s moat today. But I also think that early advantages can cumulate into sustainable ones, assuming a scale-based process kicks into gear.

But first, some context.