Wise and the business of cross-border transfers: part 1

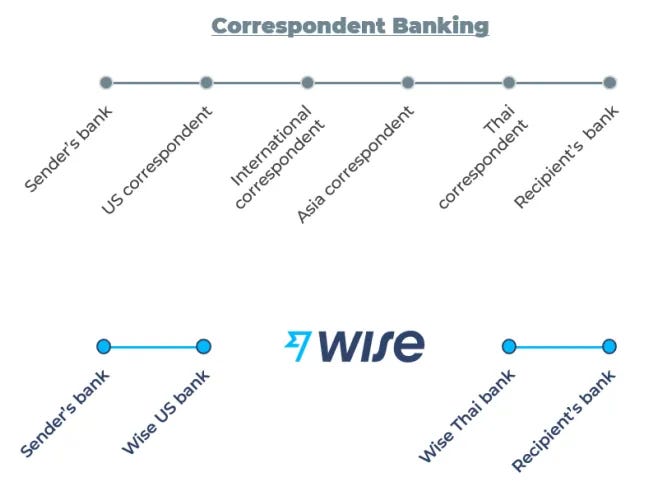

Each year, consumers the world over move ~£2tn across borders, with roughly 2/3s of that funneled through a labyrinthine network of banks1. A typical cross-border bank transaction might look something like this: Amber, a US resident with a checking account at PNC, places an order to send Rupees to her mother’s account at Seylan Bank in Sri Lanka. After ensuring there are sufficient funds in Amber’s account and running proper KYC checks, PNC directs that order to SWIFT, a communications protocol connecting more than 11k financial institutions. The PNC-originated order is routed to a US correspondent bank like Citi, which then passes it an Indian correspondent like HDFC Bank, ultimately reaching its final destination via HDFC’s direct connection with Seylan Bank in Sri Lanka.

Every bank involved in intermediating this transaction assesses a transfer fee, the sum of which rolls up to Amber as an Overseas Delivery Charge that might run anywhere between, say, ~$20 and $70 depending on the number of hops and which borders are crossed. Those fees are sometimes waived for appearances sake but smuggled in through inflated exchange rates. Banks also impose cutoff times for processing transfers. Amber might place an order at 2PM Pacific, but Citi may not receive the funds from PNC for several hours, at which point HDFC’s daily cutoff time may have already passed, leaving Citi to hold the funds overnight before sending payment instructions through. Depending on the number of time zones crossed, delays at one stage of the transfer chain can cascade downstream, compounding settlement lags. In the end, the sender typically pays between 3% and 7% of the principal in fees, while the recipient waits anywhere from 2 to 5 days to receive funds.

For all its faults, SWIFT is a useful innovation. It provides a consistent way to transmit payment details from one account to any other. Without it, any bank hoping to offer global money transfers would need to establish direct bilateral relationships with tens of thousands of other banks. SWIFT eliminates that upfront burden, but raises the ongoing cost and complexity of transmitting money from one country to another. You can imagine the opposite tradeoff, though, where an entity bears the significant upfront burden of connecting to many individual banks, but in return avoids the cumbersome process of hopping money across several nodes. That’s what Wise set out to do.

Source: Wise prospectus

In each country, Wise integrates its systems with those of local bank partners to exchange, in some standardized format, files containing payment and accountholder data. Bank partners earn fees for processing transactions on Wise’s behalf. Although these fees are significant, accounting for 27% of Wise’s total costs, they shrink as a share of rising transaction volumes, making scale essential to achieving a cost advantage.

Securing the proper licenses - which cover everything from transfers in, transfers out, different product lines (debit cards, asset management) and customer segments (personal vs. business) - to send and receive funds through partner banks is typically a multi-year diligence process in which regulators review a transmitter’s business plan, volume expectations, sanctions screening practices, and collateral holdings. Wise was finally granted a “Type 1” business license in 2023, allowing per transfer amounts greater than JPY 1mn, a full 7 years after it first launched payment services there. That said, credibility earned in one major developed market makes it easier to gain a foothold in others, and experience navigating one regulatory swamp provides a playbook for the next. It took five years for UK regulators to approve Wise’s connection to FPS; in Singapore, the process took just six months. A fintech starting from scratch could acquire the same licenses and recreate the web of relationships that Wise has weaved with banks and regulators since 2011. Still, doing so would take a hell of a long time and by that point Wise’s ever mounting volumes will have pushed it still further down the cost curve.

For senders, a series of point-to-point relationships is a considerable improvement over SWIFT. By cutting out correspondent banks and connecting directly to local financial institutions, Wise reduces intermediary transfer fees and settlement delays. Still, even bank integrations come with complications - for instance, Wise can’t control how quickly a partner bank responds to a transfer request - and transfers through partner banks are much more expensive than interfacing directly with a country's central bank.

So then the next natural step is to bypass local bank partners and access a country’s payment rails directly. This is an even heavier upfront lift than before. Regulators need to be doubly sure that Wise, which is now part of the country’s underlying debit and credit system, has redundant collateral, that its processes and infrastructure are robust enough to meet strict availability requirements and withstand various exception scenarios, like reversing fraudulent cross-border transfers, and will typically require a physical presence on the ground. Basically, all the nitty operational details that a bank partner would otherwise handle on Wise’s behalf, Wise must tend to itself.

But in exchange, Wise gains near-total control over the payment flow and can move money at the same speed and cost as a local bank. In the UK, it was the first non-bank to plug into the Faster Payments Service (FPS), the country’s real-time settlement network, cutting out roughly 90% of partner bank fees and reducing transfer times to under 20 seconds. In Hungary, a direct link to the central bank trimmed costs by 14% and pushed the share of instant transfers (< 20 seconds) from 17% to 82%. Since then, Wise has integrated with central banks in Australia (again, as the first non-bank), Singapore, the Eurozone, and most recently Brazil, where it also secured a second license as a payment institution. So in addition to tapping local rails through its 90+ banking partners, Wise has (or will soon have) direct access in six countries.

Whether through bank partners or direct connections to local rails, Wise relies on domestic infrastructure to drop funds into local bank accounts, raising the question of whether money is really crossing borders at all. On a per-transfer basis, it’s not. Wise maintains local liquidity pools in each country it serves, so what looks like an international transfer is really just a coordinated pair of domestic ones. This setup harkens back to Wise’s founding myth, as recounted in the company’s prospectus:

Kristo Käärmann and Taavet Hinrikus (Wise’s co-founders) were two Estonian professionals living in London. Taavet worked for Skype in Estonia, so was paid in Estonian kroon. At Deloitte in the UK, Kristo was paid in pounds but needed Estonian kroon to pay his mortgage back in Estonia. They devised a simple plan. Each month the pair checked that day’s mid-market rate on Reuters to find a fair exchange rate. Kristo put pounds into Taavet’s UK bank account, and Taavet topped up his friend’s Estonian account. Both got the currency they needed, and neither paid a cent in hidden bank charges.

Today, Wise is that same money-saving arrangement between two friends on a massive scale. When Amber uses Wise to send 300k Rupees to her mom in Sri Lanka, Wise isn’t literally converting Amber’s 1k US dollars to Rupees at that point in time. Instead what’s happening is Amber pays 1k US dollars to Wise’s bank account in the US and Wise pays Amber’s mom 300k Rupees from its bank account in Sri Lanka. No money crosses borders and no currencies are exchanged. One international transfer is really the product of two domestic ones. That is how Wise is able to send money “instantly”.

In theory, the money Amber sends to her mom in Sri Lanka could be offset by an equal amount sent by a Sri Lankan resident to a relative in the US (just as Kristo’s pound payments to Taaet’s UK bank account were exactly matched by Taavet’s kroon payments to Kristo’s Estonia bank account), such that no international transfer fees and FX markups ever need to be paid. Wise benefits from this “netting” effect to some degree. But, in practice, transfers bias heavily in one direction. Money transfers from the US to Sri Lanka will never be entirely offset by transfers from Sri Lanka to the US. And so, over time, the Rupees that Wise has parked in Sri Lanka will be drained to some critical threshold, at which point Wise’s in-house Treasury team will survey account imbalances and FX rates across corridors to identify which currencies it should exchange for Sri Lankan Rupees. In short, money eventually crosses borders, but it does so on an aggregated, rather than a transaction-by-transaction, basis, and after some offsetting has occurred.

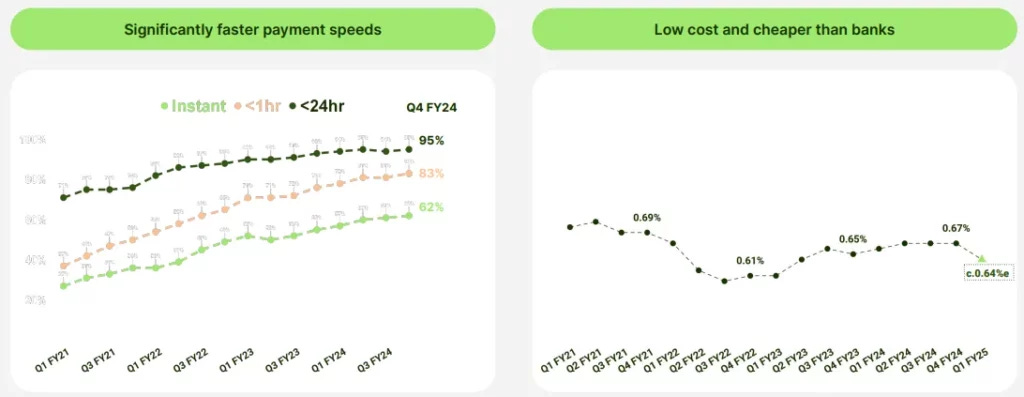

After 13 years building relationships with banks and connections to local rails in over 160 countries, Wise is positioned to transfer funds denominated in more than 40 currencies, at an average cost of just ~0.66%2, with 95% of transfers completed in less than a day and 65% in less than 20 seconds.

Source: fy24 Investor Presentation

(That Wise’s ~0.7% take rate (which is really more like ~0.35% if you exclude the fixed fee component) isn’t much lower than it was 5 years ago does not necessarily reflect a failure to scale, as that figure is a blended average across corridors that vary significantly in cost: mature routes like the UK to the Eurozone may carry fees as low as 0.35–0.40%, while transfers to emerging markets with more arcane currencies can approach 1%. It also takes time for volumes to build to a point where Wise can negotiate lower fees with bank partners and scale other fixed costs, so a recently launched corridor will carry higher costs than a mature one even if its terminal take rate is the same.)

The industry for cross-border transfers is rather fragmented. Even a prominent global bank like Citi moved just $358bn across borders in 20233, a figure that includes flows from enterprises (~half of global cross-border payments volume in 2020), which Wise doesn’t serve. JPMorgan might be moving around 3x that amount, again including B2B flows. Wise, with ~$164bn of volumes, is among the world’s largest consumer money transmitters for consumers and SMBs and even then its market share barely cracks 5%. The set of competitors also varies a lot by corridor. Flows to developing countries, where take rates can sometimes run in the double-digits, are facilitated not only by banks but by Money Transfer Operators (MTOs) like Western Union and MoneyGram, whose customers are heavily comprised of unbanked immigrants. Reflecting its origin as a cost-saving scheme between two two salaried professionals, one of whom was paying off his mortgage, Wise caters more to the white collar crowd and over-indexes to flows between developed economies, where the per-transaction sums are larger (Wise's customers transfer 6x-7x more money per year on average than Western Union’s) and rates are closer to low-single digits. Here, banks are a far more significant presence.

It's easy to understand why ~80% of Wise's customers come from traditional banks. Besides outcompeting them on speed and price, Wise also offers a far cleaner and more transparent user experience. The process of sending a transfer through the Wise app is as straightforward as it gets. When I lived in Germany some years ago and used Wise for the first time, I was stunned by how easy, cheap, and transparent the experience was. You simply fund a Wise transfer through a domestic bank or card payment and enter the recipient’s foreign account details. After running KYC and fraud checks in the background, Wise will convert currency at a mid-market rate and provide a clear breakdown of the transfer fee, FX rate, and estimated delivery time, with live updates and timestamps at each step of the transaction. This feels like magic to anyone accustomed to sending international wire transfers through banks, who usher users through clunky displays, hide fees through marked up exchange rates, provide no guidance on when funds will reach recipients nor any visibility on which checkpoints have been reached in the transfer chain.

Even if a bank could provide international transfers to consumers for less, would they ever voluntarily do so? Traditional banks are not in habit of passing lower unit costs to customers, absent competitive pressures. They are institutionally geared to hoard savings. Wise does the reverse. It abides by a cost-plus model, where any cost reductions beyond those required to sustain a target margin are recycled into lower take rates for users. This policy is enforced at a granular level, such that no corridor, product, or customer segment is allowed to cross-subsidize another. Wise is fanatical in its pursuit of being the cheapest and fastest way transmit money. Its maxim, “Mission Zero”, encapsulates the continuous erosion of fees up until their ultimate elimination. Even if aspirational in reality (you can’t actually charge 0 fees and turn a profit, right?), the credo is treated internally as though it were literal. Peruse the vast compendium of former employee interviews on Tegus and AlphaSense if you dare. That no, really, everyone at this company does in fact have immediate recall of this central tenant and strives toward its actualization is echoed again and again.

In addition to the analog moat of licenses, bank partnerships, and rail connections - assembled piecemeal over more than a decade - Wise operates scalable cloud infrastructure to manage liquidity and onboard customers efficiently. Machine learning models forecast which liquidity pools are likely to be in surplus or deficit based on expected fund flows, enabling Wise to shift capital across countries ahead of partner bank cutoff times and ensure sufficient balances to support instant transfers. The same technology also accelerates customer onboarding and verification. Manual checks that used to consume thirteen agent hours now only take up two. In fy21 (ending March 2021), Wise automated 91% of document reviews for consumers with greater than 90% accuracy and resolved 80% of cases in just one interaction. One can only assume these metrics have improved since then.

Wise’s cost obsession shows up in its frugality across areas of the business that don’t directly impact the customer experience. As a former Wise employee put it in this Tegus interview: “You have a stipend for travel. You can barely buy any food with it. You're always on overnight flights, it's something which he generates consistently across every person in the business”. Another elaborates: “There's also a very strong internal culture that everything we spend in marketing is customers' money….There's this very strong sense that all the dollars that we spend are customers' money, and they're trusting us to make smart decisions with it”.

Granted, it’s a huge cliche to say that traditional banks are stodgy, bloated institutions running on antiquated tech who have lost the script on innovation and customer service. But does anyone doubt this is true? Wise has more than 800 engineers split across ~120 autonomous teams - split by region, then by product, backend service, or feature - who are encouraged to arrive at solutions on their own, fostering a rapid problem-solving cadence. It pushes more than 120 updates a day while a large banks, according to Wise, might release more like one every 3 to 6 months. CEO Kristo Käärmann, who owns 18% of the company and retains the same number of shares today as he did at the time of IPO three years ago, is still very much in founder mode. He is known to work directly with engineers closest to a problem, a scenario impossible to imagine at a large European bank.

I can’t think of a significant digital banking initiative launched by a traditional bank that succeeded on its own two legs, even as several failed efforts come to mind: Finn (JPMorgan), Greenhouse (Wells Fargo), Simple (BBVA), and Bo (RBS). Notably, in 2020 Santander launched a cross-border transfer app, PagoFX, that was intended to compete with Wise and could lean on the advantages of a parent with banking licenses South America and Europe. It was ultimately forced to shut down less than two years later. Earlier this year, HSBC launched a competing app, Zing, in the UK. In assessing 0.2% of funds on conversion and no transfer fees, it charges lower fees than Wise, Revolut, and other money transmitter of note in nearly all of the dozen or so corridors I checked. I doubt this is sustainable. There’s almost no way that Zing enjoys lower unit costs than Wise, as it has nowhere near the volumes. And to power its flows, the company relies on a third party, CurrencyCloud (owned by Visa), a euro-centric service provider with no direct connections to any central banks.

Anyway, most traditional banks are simply not set up to facilitate or prioritize consumer and SME money transfers. With maybe the exception of Citi and JPMorgan, global banks are better described as a collection of local banks, with no central treasury management system coordinating flows across them. They offer competitive exchange rates for cross-border flows only if the currencies in question happen to align with those the bank happens to be transacting in that day for its own security-hedging purposes. Also, to minimize risk, banks are reluctant to enter into any more relationships than they absolutely must, hence their continued reliance on SWIFT even as bilateral connections present a faster, lower-cost path for customers.

Adyen had the right idea. The best way forward is to “start over again”. And much as Adyen, through the rapid product innovation enabled by a single unified platform, stole gobs of share from legacy merchant acquirers who were hobbled by a patchwork of poorly integrated acquisitions, so too has Wise, through its streamlined infrastructure of direct bank relationships and user-friendly products, overseen by empowered teams and coded on modern cloud infrastructure, siphoned away cross-country flows from legacy banks who transact through SWIFT and build on ancient tech.

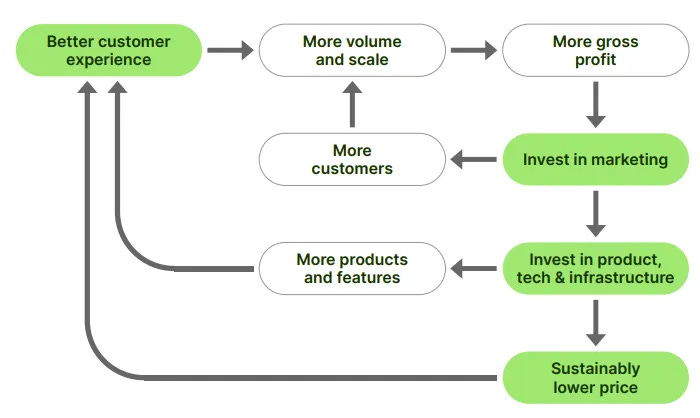

Growing volumes drive lower unit costs through lower bank transfer fees and greater leverage on engineering and product development, which in turn produces more gross profits that, beyond a sustainable margin target, are reinvested in product, marketing, and price, which in turn draws more volume (this is akin to Ryanair using cheaper tickets to attract more passengers, who are then leveraged to negotiate lower landing fees and aircraft prices, with the resulting savings then feeding back into cheaper tickets). Enchanted by low fees and fast transfer speeds, customers promote the service to friends and family - around 2/3 of new customers come through word-of-mouth - reducing the Wise's reliance on paid marketing to drive growth. In its most recent fiscal year (ending March 2024), Wise spent just £37mn of marketing against £119bn of transfer volume while LTM through June ‘24, Remitly spent $282mn against $46bn).

The flywheel looks something like this:

Source: fy24 presentation

But to what extent can Wise leverage its low cost advantage in cross-border transfers to other product domains and what are the soft spots in its business model? Stay tuned for part 2!

Wise and the business of cross-border transfers: part 2

Disclosure: At the time this report was published, accounts I manage owned shares of $V, which owns CurrencyCloud. This may have changed at any time since

Traditional money transfer operators account for 13% and other non-banks another 18%

the fee a customer pays scales down with volume, with particularly large transfers assessed fees as low as 0.18%

see slide 3 in this presentation from their Jun ‘24 Investor Day

What % of transactions are internalized?

Internalized by being either:

1. Netted off or

2. (Looking forward) Both send and receive are connected to the Wise Platform…

Data isn’t disclosed, but conceptually, its an interesting thought process.

I am not sure people understand the network effects that are (slowly) being built here.

Great write-up. Looking forward to reading the part 2. I agree that Wise has a massive regulatory advantage over other fintechs if they were to try to replicate their approach. Visa and Mastercard have bigger scale and reach, though. Isn’t a product like Visa Direct a direct competition for Wise Platform and indirect competition for Wise D2C product (of course banks adopting Visa Direct could still have inferior UX to Wise)?