thoughts on Watsco

While investors continue to be enthralled by AI and all things Tech, I can’t help but think there are easier opportunities being overlooked in boring industries that don’t make the business news or saturate our Twitter feeds. So you’ll have noticed that in recent months, I’ve been looking beyond the white hot center, concentrating my research efforts on neglected Boomer stocks that have gotten crushed due to near-term macro weakness, AI threats (real and perceived), and other industry headwinds. In some cases – Align and Booz Allen – I’ve passed. In others – LTL carriers, Gartner – I remain on the fence. And in a handful – Trex, Constellation Software, Avantor, and Watsco – I’ve started positions.

It’s been more than five years since I last wrote up Watsco. Testament to the durability of Watsco’s moats and the stability of the HVAC industry, the core underpinnings of the investment case haven’t changed much, even in the midst of a pandemic, inflation, tariffs, and massive regulatory-driven product shifts.

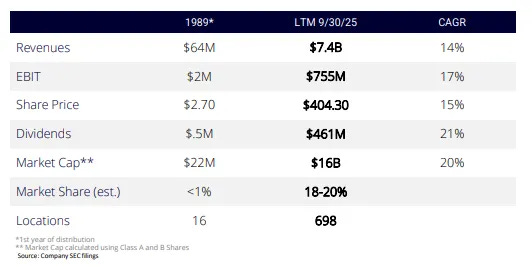

To recap: Watsco was founded as a manufacturer of HVAC components in 1956 by William Wagner1. In 1972, William sold his 38% stake to Watsco’s current CEO and Chairman, Albert H. Nahmad, who pivoted the business toward HVAC equipment distribution in 1989 with the acquisition of Gemaire, one of Florida’s largest residential AC distributors. Watsco has since acquired, in whole or in majority part, more than 70 independent distributors, growing into the largest player in a fragmented industry made up of ~1,400 competitors, who sell to an even more fragmented base of ~150k+ contractors, most of them mom-and-pops.

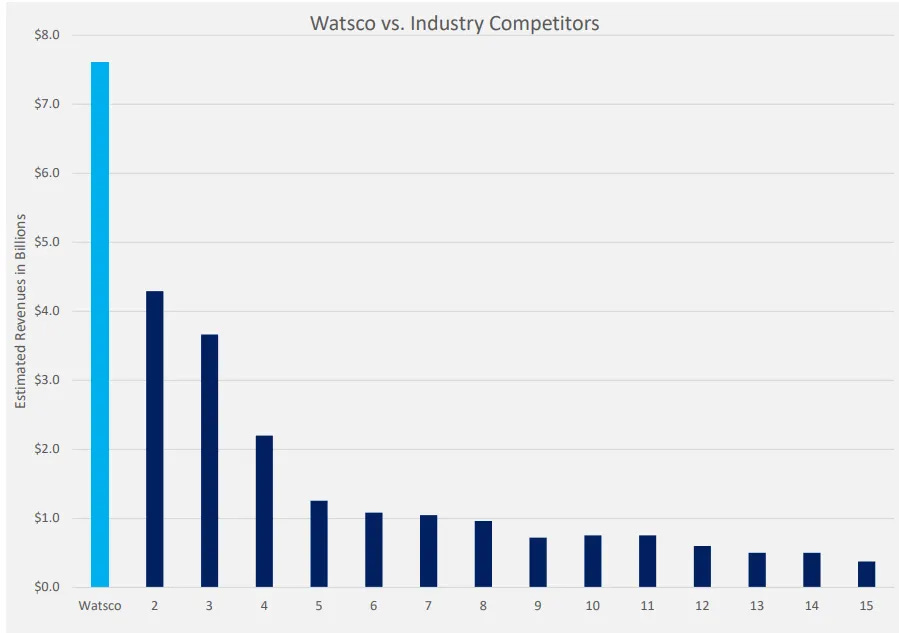

The above exhibit shows Watsco’s market share at 18%-20%, though in other contexts management has pegged it at ~12%. In either case, Watsco is significantly larger than the next two largest distributors, Lennox (who is also an OEM) and Ferguson, who each do ~$3bn of HVAC revenue.

Source: Watsco

Watsco exhibits some of the classic behaviors of fan-favorite serial acquirers. It eschews bank-led auctions, scouts healthy distributors (”regional superpower businesses”) with strong local contractor relationships for years, sometimes decades, and presents itself as a “forever home” for owners who themselves or their parents or their parents’ parents built the business from scratch and care about what happens to employees and contractors after they’re gone. From Thoughts on Watsco and some businesses like it:

The distributors that Watsco acquires are typically family-owned operations with deep local roots and entrepreneurial cultures, bound to the contractors they serve through relationships that stretch back decades, sometimes generations. If you look through Watsco’s list of acquisitions, what you’ll find are businesses with maybe 10 to 15 branches spread across a few markets, bequeathed over several generations. Relationships, reputation, and longevity are critical. The owner of a 3rd generation family operator isn’t just going to sell to a financial mercenary who’ll gut the business and flip it after a few years. Watsco has never participated in an auction or hired a banker for any of its deals, preferring to instead maintain ties with local distributors, fostering goodwill and trust so that when those operators finally decide to sell, they find in Watsco a permanent home where what they’ve built over so many years will be preserved intact.

Watsco typically pays ~5x-7x EBIT and grows the acquired entity’s profits through organic growth rather than through cost cuts. Acquired businesses retain their trade names and run their day-to-day affairs as though they were independent, standalone entities, even as they sometimes share a common Watsco-powered tech stack and centralize procurement for certain products.

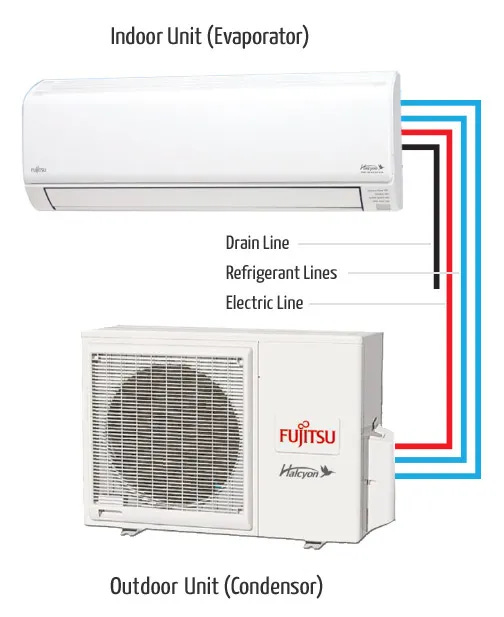

At a high level, HVAC equipment comes in one of two categories – ducted and ductless. Ducted systems – standard in the US, where the housing stock is heavily skewed toward single-family homes – use a central unit to distribute conditioned air throughout a home through a network of ducts hidden in walls, ceilings, or floors, with air delivered through vents in each room. Ductless systems (primarily heat pumps) do away with the ductwork, connecting an outdoor compressor to one or more indoor units mounted directly on walls or ceilings in individual rooms, as seen here:

In North America, Mitsubishi is the largest ductless player and Watsco is Mitsubishi’s largest customer. Asian manufacturers like Daikin, Gree, and Fujitsu are also big players. Carrier, historically focused on conventional systems, formed a ductless joint venture with Midea in 2008 and, in 2022, acquired full control of the Toshiba Carrier’s residential HVAC joint venture.

Although ductless units make up 10%-15% of Watsco’s volume today, adoption continues to rise as contractors gain familiarity with these systems and homeowners lean into higher-efficiency options. Watsco refers to ductless as an “increasingly important component of our business”, growing ~teens/twenties from 2022 to 2024, far outpacing the tepid growth of conventional ducted systems during those years and delivering higher margins to boot (and this was despite the fact that state rebates promised by the Inflation Reduction Act failed to materialize to anywhere near the degree people expected).

The HVAC sales flow is straightforward. A homeowner with a malfunctioning HVAC unit calls a local contractor. The contractor visits the homeowner to diagnose the problem, then purchases the equipment and components they need from a nearby distributor, who in turn is likely to source products from one of just a handful of HVAC manufacturers, among them Carrier (whose brands include: Carrier, Bryan, Payne), Daikin (Goodman), Rheem (Nortek), Trane, Bosch Group (York), and Mitsubishi. These vendors, most of whom were founded before World War II, account for 90% of HVAC units shipped in the US. Because the homeowner is unlikely to be familiar with any of these brands and will almost always defer to the contractor’s expertise, the distributor’s end customer is the contractor who sells the HVAC system, not the homeowner who ultimately buys it.

When most people think of distribution, they imagine a “many-to-many” topology, where a distributor buys from a fragmented base of manufacturers and sells to a fragmented base of customers. Fastenal and, to a lesser extent, Pool Corp. fit that familiar mold. The HVAC ecosystem differs on the left side of that equation. Distributor purchasing isn’t broadly sourced, but instead funneled into a small handful of OEMs.