[KNSL] Kinsale is built for speed

One way to carve up the investment universe is between standardized products, like index funds, that run on fixed rules and scale effortlessly, and bespoke ones, like distressed credit or esoteric ABS, where the risk is niche and full of weird wrinkles.

In the world of property & casualty insurance, “admitted” lines are more like index funds, characterized by homogenous, well-understood risk parameters that are underwritten over and over again at massive scale. They fit within the investment equivalent of “style boxes”. Carriers file standard policy forms with regulators and their policies are backed by state guaranty funds. The auto policy on your Honda Civic falls in this category. So might, say, a small business policy for an Italian restaurant in a non-cat zone.

By contrast, “excess and surplus” (E&S) lines assume liabilities that are hard to place in the admitted market due to some quirky hazard or complexity that requires unusual terms or exclusions…that might include, for example, a sketchy nightclub; a cannabis dispensary; a contractor working on a high-rise exterior near wildfire-prone areas; a Florida condo association overseeing buildings with unresolved structural issues. Regulatory oversight still applies, but the rules are looser. Rates aren’t pre-approved, forms can be customized, and coverage can be tailored by carving out the ugly bits, demanding higher deductibles, or imposing tighter limits.

There is no hard and fast distinction between admitted and E&S exposure; as certain risks become better understood and more actuarially tractable, they often migrate from the E&S market into the admitted side. Cyber risk and ridesharing endorsements are two such examples. Premiums flow the other way too. Where E&S was once considered a market of last resort, it has increasingly become a primary destination for risks that may have historically been placed with admitted carriers. You see this happening with homeowners insurance in catastrophe-prone states like California, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana. Admitted insurers, constrained by regulated rate filings, are unable to reprice fast enough to respond to exacerbating loss trends, forcing them into retreat. E&S carriers, who enjoy rate and form flexibility, are stepping in to fill the void.

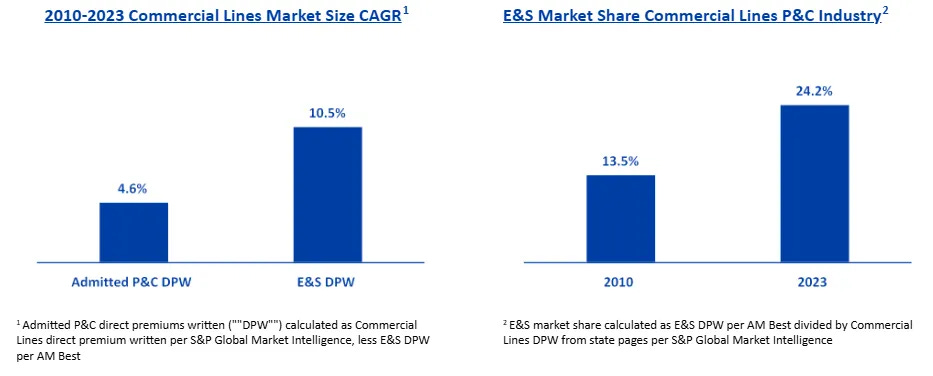

Management points to a 30-year history of E&S outgrowing the admitted market and, according to A.M. Best, E&S premiums as a share of P&C premiums has more than doubled over the last 20 years, from 4.3% in 2001 to 10.1% in 2021. Within commercial lines, where Kinsale predominantly plays, E&S share is even greater:

Source: Ryan Specialty 2024 10-K

Founded in 2009 by CEO, Chairman, and ~4% owner Michael Kehoe – who previously ran James River Insurance, a competing specialty carrier, from 2002 to 2008 – Kinsale Capital focuses on the less competitive end of the commercial E&S market, serving commercial small/mid-sized accounts1. In 2024, ~2/3 of its gross written premiums came from casualty lines, ~1/3 from property.

Insurance is a commodity service where the cheapest quote usually wins. As such, you generally want to bias your investment search to the lowest cost players (see my write-ups on Admiral and Protector Forsikring). But determining which carriers enjoy a sustainable cost advantage isn’t necessarily straightforward because, as Buffett once quipped, insurance accounting is like a self‑graded exam. Carriers estimate their own loss reserves and, whether due to incompetence, wishful thinking, or fraud, can make a book of business appear more profitable than it actually is for a while.

This is particularly true of “long tail” risk, where claims may be paid out many years, even decades, after a policy is written. Asbestos exposure is perhaps the most canonical example of a long-tail catastrophe. Workers exposed to asbestos from the 1940s through the 1970s fell afflicted with causally related diseases, like mesothelioma and lung cancer, decades later. I remember seeing late night TV commercials recruiting plaintiff for class action asbestos lawsuits in the 1990s. Claims are still being filed today.

But there are more garden variety cases. A general contractor might find themselves on the hook for construction defects that don’t show up until five years after the job is completed. Or a radiologist could be sued for misreading a scan of what years later turns out to be cancer. Actuaries set aside some percentage of premiums as reserves to account for such scenarios. But it’s hard to predict the magnitude of those risks so far in advance. Medical costs, legal fees, and jury awards could be far higher when claims are ultimately paid. Expanding theories of liability and rising jury sympathies (sometimes referred to as ”social inflation”) can dramatically lift claim costs over time.

Generally speaking, for most casualty line (not stuff like toxic torts and environmental liability) the more time that passes after a policy is written, the less likely surprise reserve developments are to materialize, as an ever growing proportion of ultimate losses will have already been reported and adjudicated. A chronic abdominal pain that a patient experiences today is unlikely to trace back to a gallbladder removal from 5 years ago, as complications from that procedure would almost certainly have manifested much earlier.

Short-tail lines are vulnerable to sudden adverse events too, but claims typically surface and resolve quickly. When a hurricane rips your house apart, trust me, you will know immediately and won’t wait 5 years to report the event. It’s the lingering uncertainty that makes long-tail casualty so insidious. Injuries take time to manifest, liabilities unfold slowly, and claims can deteriorate long after the policy period has closed.

No approach to assessing reserve adequacy on long-tail lines is foolproof. But two commonly accepted methods provide useful signal.

The first involves looking at loss development triangles. A loss triangle, as featured below, shows how the insurer’s estimate of ultimate losses2 for policies written in a given “accident year” changes over time. If an insurer is reserving accurately and conservatively, subsequent adjustments to a given accident year’s initial loss estimates (initial “loss picks”) should be modest, and when changes do occur, they should skew downward, reflecting a better-than-expected loss experience that allows some portion of reserves to be released.