[MTCH] Match Group

Online dating has easy parallels to other online social experiences that if taken too seriously can lead to dubious outcomes. A dating app is like social media in that there are lots of people broadcasting themselves, making connections, and seeking validation. You might “like” a photo on Instagram as you might right-swipe on a photo in Tinder or Bumble. So as Tinder, Match Group’s largest property – accounting for 66% of paying users (”payers”), 60% of revenue, and 80% of EBITDA – ballooned to ~75mn monthly active users, it must have seemed only natural to consider human relationships in a more abstract, all-encompassing way. They could not only mediate romance but “social discovery”, “interest groups”, and eventually, “social entertainment”. They could foster connections that “span geographies, demographics, relationship status and genders in ways that dating services cannot, effectively providing a much larger addressable market than dating”.

When Meta began to push entertainment over friend graph content and talk a storm about the metaverse, Match maybe felt that that was something they should think about too. Those thoughts eventually crescendo’ed into the $1.7bn acquisition (8x revenue) of Hyperconnect in 2021, the largest in its history. Hyperconnect got 75% of its revenue from Asia and operated through 2 brands: Azar, which enables one-to-one live video chat, and Hakuna, a multi-party live streaming app. Its advanced video technology could, Match believed, create a “metaverse-based experience” for social discovery and be integrated into its portfolio of apps. Meetic, a European dating app owned by Match, used the technology to launch “Live Rooms”, where small groups of people could hang out and shoot the shit. In Hyperconnect’s “Single Town”, user avatars ambled from one virtual location to the next. We now know that these metaverse ambitions, which may have seemed reasonable in the disco fog of the post-COVID orgy, were a massive overreach.

The expansion never made much strategic sense. Match was trading off a dominant position in the growing niche of online dating for a subscale position in the amorphous expanse of social media, where it was pitted against impossibly strong competitors. And you can see how an app with a reputation for facilitating hookups, when combined with a virtual goods economy and video streaming, could degenerate into a pretty unsavory place.

More than that though, people appear to want to represent different selves in different platforms. The stuff one feels comfortable sharing with potential mates on Hinge will differ from stuff they share with friends on Facebook or with colleagues on LinkedIn. Facebook Dating, which can pull in Instagram Stories and add Instagram followers and Facebook friends to “Secret Crush” lists, has famously flopped since launching in 2018. Hinge, the second largest Match property, contributing 8% of payers and 11% of revenue, soared even after it stopped leveraging Facebook’s social graph to match singles. Bumble’s derivative offerings – Bumble BFF for discovering platonic friends and Bubble Bizz for developing professional relationships – don’t appear to have gotten much traction.

In short, dating apps have failed to compete with other social graphs on their own terms and IRL friend graphs don’t appear to bring meaningful advantages to online dating. This doesn’t mean certain social media mechanics can’t be carried over to dating apps. Tinder’s “Explore” tab, where users are organized by shared interests and relationship intent, seemed like a reasonable idea: a low risk way to efficiently sort matches on an app where users typically don’t provide any profile information beyond photos. But it was designed in the spirit of casual virtual hangs and hasn’t made any lasting impact on Tinder’s flagging user growth.

Dating apps are a utility. Where they go wrong is in positioning themselves as social hubs rather than as tools that take the burden off tired swipe thumbs. The functional orientation of dating apps is reflected in the way they monetize. Facebook is concerned with remaining relevant to younger audiences only in the sense that engagement drives ad revenue, so they’d rather have more of it than less. They aren’t thinking about demographic mix through a zero sum lens. Because Meta can personalize what it injects into a user’s feed, it is the amount of relevant content that matters, not the relative mix of men vs. women or young vs. old on the platform per se. So the two-sided network effects of social media are instantiated as engaged users on one side and advertisers on the other.

By contrast, the two-sided network effects in dating apps are expressed within the user base itself. The vast majority of revenue that any dating app realizes comes from men, who outnumber women by ~2x-3x1 and pay in order to improve their odds of securing dates with them. While engagement matters, where that engagement comes from is just as important. Dating apps try so hard to create compelling experiences for women for the same reason that bars offer them free drinks and bouncers block you and your boys even as they wave in a large bachelorette party. Single men will swipe right on just about anyone. There is no need to cater to them. If anything, barriers are required to keep them from upsetting the gender balance too much and bumming out women, who are not only fewer in number but tend to be far more parsimonious with right-swipes besides.

Tinder popularized a number of features that catalyzed its explosive rise just as smartphone adoption was taking off. Sparse profiles requiring nothing but photos made it easy to onboard. A freemium revenue model made it easy to trial. The “swipe” was suited to casually filling interstices of time throughout the day. But just as critical to Tinder’s success was the double opt-in feature, where both parties had to swipe right on each other before private messaging could commence, a feature that helped dam the deluge of unwanted messages from random guys, which was a big problem for women on Gen 1 desktop dating sites like Match.com and OkCupid (though this continues to be a major issue, with ~2/3 of women under 50 on dating apps experiencing harassment in one form or another).

So with online dating, we have a setup where men, fueled by the dopamine release triggered by the variable rewards that come from the unpredictable timing of matches, compete with one another for the prize of securing dates with a scarce supply of women. This looks an awful lot like gaming. In this Time article from 2014, Tinder’s co-founder Sean Rad explains “We always saw Tinder, the interface, as a game….What you’re doing, the motion, the reaction.” You might even hypothesize that gaming is an outgrowth of the same competitive instinct, honed through evolutionary pressure, required to win mates. It then seems natural that Match’s latest CEO, Bernard Kim, spent 6 years at Zynga and close to a decade at Electronic Arts, and that before Bernard came on board, Match was replicating monetization dynamics pioneered by online gaming.

There was a time when online games made money through a “play to win” model where players had to purchase expansion packs and fancy gear to stand a realistic shot of advancing. But buying your way to victory seemed unfair and today most monetize through a combination of advertising and cosmetic in-game purchases that enhance a player’s experience without improving their chances of winning. Advertising never took hold in online dating. It’s a tiny part of Tinder’s revenue. I guess there’s not much data to target against. On the other hand, a la carte (”in app”) products are a meaningful source of revenue for Tinder, comprising ~25%-30% of its total. But unlike skins purchased in an online game, Boosts (which allows you to be one of the top profiles in your area for 30 minutes) and Super Likes (a blue star you can tap on someone’s profile that lets the other person know you really like them and prioritizes your profile on their card stack) in Tinder are purely functional.

The most enduring gaming franchises have avoided the hit driven paradigm that used to characterize the space by fostering communities. A gamer can earn status in those communities by procuring badges with skilled play or even by purchasing expensive skins that signal commitment or whatever. Dating apps aren’t like that. These are utilities, not communities. There is no signaling value or bragging rights to securing dates. The rewards from doing so are private. And I’ve got to imagine that spending boatloads of real money on Tinder Coins that you use to acquire virtual collectibles and buy your way to the top of card stacks could backfire? You don’t want to appear desperate or mark yourself as someone who takes online dating too seriously. That’s a turn off for women. There’s a reason your subscription status isn’t displayed on your Tinder profile and I can imagine that Boosts and Super Likes might dilute your prospects if women know you purchased them. I suppose part of the reason everyone on Tinder has a quota of Super Likes, regardless of whether they buy them or not, is so it’s not obvious to someone who receives one that the sender paid for it.

The analogy to gaming breaks down in a more fundamental and obvious way. There are no skills to master. Interesting photos that highlight facets of your personality can move the needle a bit, but whether you are right-swiped or not is primarily a function of your physical attractiveness relative to that of the swiper. In real life, where there are opportunities to flex other assets besides looks – intelligence, sense of humor, kindness, social status – over a sustained period, whether that be at school, with friends, or in the workplace, you will find plenty of couples who are mismatched on attractiveness. But in raw stranger-to-stranger encounters, particularly on Tinder where pictures are pretty much all you have to go on, physical appearance will be the dominant filter.

It used to be that Tinder assigned you a desirability score based on the mix of right and left swipes you received relative the scores of users swiping you, among many other factors. Users with similar scores made their way to each others’ card decks. Eventually, as Tinder scaled and accrued more user data, that competitive ranking system gave way to one where users in your card stack are similar to those who were right-swiped by people who tend to right-swipe the same profiles as you, which is apparently how Hinge matches users too. In either case, though, you more or less end up in a matching pool with people who are comparably desirable. And that’s a good thing. If you’re a 2 in the looks department, you do not want a card stack of Margot Robbie’s. You may think you do, but you don’t. You may as well spend your time rating photos on “Hot or Not” because you will almost never get right-swiped. Online dating is nice in that it conveniently introduces you to mates while removing the embarrassment of in-person rejection. It also creates a rather efficient market that kills the dream a little for everyone.

Within algorithmically determined matching constraints, Tinder is still monetizing off similar “pay to play” tactics that gaming companies abandoned due to the deleterious effects on the broader ecosystem. The analogy here isn’t great, as ~3/4 of Tinder’s revenue comes from subscriptions, whose benefits include things like “unlimited rewinds”, “see who likes you”, “passport” (where you can match with users in other cities), and “hide ads” that shouldn’t degrade the experience for other users:

But Super Likes, Boosts, and Unlimited Swipes – which are bundled into subscriptions, with Superlikes and Boosts available as a la carte purchases to boot – crowd out consideration for non-paying users and disrupt the match order that Tinder’s algorithm might otherwise find optimal.

Of course, social media also wrestles with an inherent tension between monetization and user experience. But compared to Instagram, which has as many ways to keep users engaged as there are varieties of entertaining content (not to mention, a relevant ad can be as compelling as organic content), a dating app has far fewer moves on a far smaller surface area. There are this many singles in a 10-20 mile radius and the job is to match those singles as efficiently as possible. That’s pretty much it. The post-matching experience is unpredictable and entirely outside Tinder’s control. There is no date rating system. You can understand why Tinder and others were tempted by metaverse experiences. And monetization is confined to short-term subscriptions and boosts because users don’t expect to spend a year or even months on a dating app, even if they ultimately do. This goes hand in hand with the classic tension of online dating as a business. The better the service is, the sooner you’ll be off it, and so subscribing on an annual basis feels like paying more for a worse product. That’s why “churn”, while almost certainly through the roof, isn’t relevant in the way we traditionally think about it. Even Tinder subscriptions feel less like subscriptions than they do product sales.

The other challenge is that while match liquidity begot by network effects is the governing moat for a dating app, it doesn’t lead to winner take all outcomes as there are many vectors along which network effects can be spun. While Tinder may be the largest dating app on the market, with 8x as many payers as Hinge and 4x as many as Bumble, it co-exists alongside a very long tail that encompasses a wide variety of apps catering to different races, religions, sexual orientations, and sensibilities. Even mainstream competitors like Hinge and Bumble successfully counter-positioned against Tinder by emphasizing serious relationships. Hinge (”designed to be deleted”) requires responses to prompts and demands 5 times the 3-4 minutes it takes to sign up for Tinder. Bumble is like Hinge but with strong brand messaging around women’s safety and empowerment that is reinforced by product mechanics (women are required to send the first message).

Dating apps inspire no brand loyalty. They aren’t held together by friend or interest graphs that keep users from experimenting with competing apps. People will typically multi-home across 3 or 4 apps at once, re-creating network liquidity across them to some degree. Features like voice texts, video, badges signaling seriousness of intent are easily replicable. All this has created the conditions for an unstable industry structure, with market shares radically shifting every few years, as chronicled in this video from Data is Beautiful.

Since it was incubated within IAC in 2012, Tinder has gone on to become the most popular global dating platform, with around 75mn monthly active users (to put this in perspective, in the year of the iPhone’s debut, the largest dating site, Plenty of Fish, had about 8mn MAUs). According to Pew Research, 46% of US online dating users, including 79% of those between the ages of 18 and 29, report having used Tinder at some point:

But like so many apps before it, Tinder too is now wrestling with stagnant user growth. They are trying to combat this headwind by appealing to Gen Z users and women who might otherwise be drawn to more substantive connections on Hinge and Bumble, with marketing campaigns that de-emphasize its reputation as a casual hook-up app. But brand marketing that tells users what you hope to be known for will not work if the product is still grounded in low-friction onboarding and shallow swipes, and altering the core product or requiring users to invest more time on profiles upfront risks alienating existing users and further constricting top-of-funnel growth.

With a series of CEOs and product managers arriving with a plan to revitalize what they correctly recognized as a stale user experience and then resigning after failing to do so, it’s hard to escape the feeling that Tinder may just be out of moves when it comes to user growth, that Match’s most significant cash cow is now in senescence, following the all too familiar path of every other dating app that exploded in popularity only to slip into irrelevance. Management has long talked about optimizing for revenue rather than either payers or revenue-per-payer per month (RPP). Even so, bears will point to the mix of revenue growth increasingly coming from RPP at the expense of payers as evidence that top-of-funnel expansion and payer conversion have gotten much harder to come by. They will say that Tinder has matured to point where a greater mix of revenue growth must now come from extracting more value from the payers it already has.

A salient example of this is Tinder Select, a $500/month membership tier that was rolled out to the most active 1% of users in September. By now, we’re all familiar with the extreme tail in mobile monetization. In gaming, a small fraction of users will spend boatloads on cosmetic features for status and social connectedness. The top 1% accounts for half a publisher’s revenue or whatever. But I’m not sure think Tinder is amenable to nearly the extreme monetization tails you see in gaming. There are no status awards to win, no community to impress, and limits on how much Tinder can improve your matching prospects or date experiences. And if Tinder Select is that good at matching you with the right mate, well, you’re not going to be paying for very long. From an avid payer base of ~104k (1% of 10.4mn total payers), how many actually go for this and over what stretch of time? Do you get to, say, $50mn (5% of LTM EBITDA) by assuming 10k members at $500/month for 10 months? 20k members at $500/month for 5? My intuitions fail me here.

The concern is not that the online dating market is tapped out but that the subset of users drawn to casual swipe mechanics largely is, and management’s range of motion is constrained by the casual, low friction on boarding that made Tinder such a viral sensation in the first place. Over the years, they’ve introduced all sorts of initiatives (Swipe Night, Explore, Hot Takes, Vibes, video chat, the “Starts with a Swipe” marketing campaign) whose impact on engagement, while promising at first, ultimately proved ephemeral. Tinder can play around with different monetization tactics on a given set of product features, but this only goes so far. At some point they’ll need to find durable, product-led ways to expand the efficient frontier, improving match quality and swipe efficiency across the board, expanding the top-of-funnel by appealing to Gen Z users, and attracting more women so payers can enjoy higher hit rates without unduly damaging the experience for non-paying users. They’ve announced a few so-so sounding things, like quizzes and prompts designed to add texture to profiles and more curated profiles for women, but I’m not sure why these rollouts should work when so many others like it have failed.

I’ve viewed Match’s prospects through a pessimistic lens thus far. But the company has several things going for it too.

First, while historically even once leading online dating sites abruptly lost significant share in a matter of years, that share loss occurred in the context of a rapidly expanding market. Share loss does not necessarily imply an imploding user base (consider that between 2014 and 2019, Tinder lost several points of market share even as its MAUs grew 44%2). Match Group consolidates its atrophying legacy brands (namely, Match, Meetic, OkCupid, and Plenty of Fish) and its nascent ones (namely, BLK, Chispa, and The League) in a single segment (”Emerging & Evergreen”) that is declining low-single digits. Its non-Tinder revenue in 2016 – which basically reflects all the old stuff, including a full year of Plenty of Fish – was about $950mn. Based on management’s limited disclosures, it looks like those brands did around ~$650mn in 2022 and maybe ~$590mn this year, implying ~6%-7% annual contraction over the last 7 years. So while Match’s musty brands have declined, they’ve done so at a more measured pace than one might think, especially considering that, as desktop native apps, they were on the wrong side of a generational platform shift. I don’t want to minimize the structural challenges. Those legacy properties saw revenue declines accelerate to 11% over the last 2 years. I only mean to point out that just because a dating app fades out of conversation does not mean it step-functions to zero.

It’s also worth setting aside historical comparisons to just consider whether it would even make sense to launch a new mainstream dating app today. How would you do it? Tinder found product-market fit with swipes in 2012. Hinge was founded at about the same time, Bumble just a few years later, both counter-positioning against Tinder with serious relationship intent. There are and will continue to be countless niche dating apps but I feel like Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble pretty much have the mainstream segment covered. I’m not sure what new product innovation you’d launch from scratch today on mobile that hasn’t already been tried to draw the marginal user away from the liquid networks spun up by those established brands. That all three are all successfully pushing price testifies to the absence of viable alternatives.

Second, while bears will interpret Tinder’s emphasis on RPP gains at the expense of payer growth as evidence that Tinder has saturated its market and is now resorting to value extraction, a more charitable interpretation – the one management obviously encourages analysts to take – is that Tinder’s past payer count was inflated by sub-optimal monetization. With aggressive pricing having now shaken out the weak hands, Tinder is building off a somewhat lower, reset base and can deliver a more even contribution from payers and RPP going forward. There is some early evidence of this, with payer losses attributable to US price hikes dissipating in 3q23, even with RPP growing by 8% q/q.

In 2q23 management launched weekly subscriptions in the US, which had the predictable impact of immediately juicing payer numbers, some of whom then churned off. But those declines should also settle over the next few quarters. We’ll see!

Third, to some extent Tinder’s durability is born out by the instability of its management. Tinder is now on its 6th CEO since 2015, Match Group is on its 4th. Various product managers and marketing officers have come and gone along the way. Former employees consistently complain about abrupt shifts in product strategy brought about by crazy turnover in the executive ranks. And yet, amidst that chaos, Tinder has 11x’ed revenue and 6x’ed payers.

On the back of Tinder’s vertiginous rise and with Hinge following in Tinder’s wake, Match Group’s EBITDA and free cash flow (including stock-based compensation and excluding a significant litigation settlement in 2022) have grown by 22% and 20% per year, respectively.

So on the one hand, you could characterize Match as a directionless company plagued by years of inconsistent product direction and mismanagement. On the other hand, what better demonstration of product-market fit than Tinder sextupling payers despite said mismanagement, to say nothing of the stunning traction at Hinge? Match and Tinder’s current CEO, Bernard Kim, has been in place for almost 18 months. It has yet to be seen whether this ex-gaming executive proves a good fit for a dating app. But so far he’s made what I think are sensible moves in retiring Tinder Coins, swearing off big-ticket M&A, dropping the metaverse blatherskite pushed by his predecessor, and pursuing less radical blocking and tackling maneuvers around monetization and product experience.

Fourth, Hinge is one of the fastest growing mainstream dating apps on the market and Match owns it. They paid somewhere around $25mn in 2018 for an asset whose revenue is today run-rating at $400mn, having grown by 43% from a year ago.

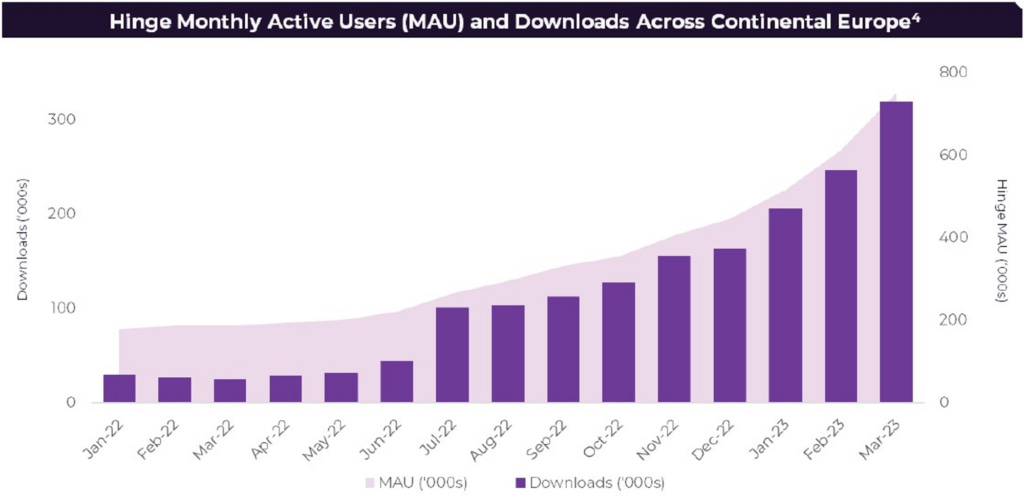

In the 5 years since Match acquired a majority stake, Hinge has gone from the 13th most downloaded app in the US to the 3rd3. It has exploded in popularity across continental Europe – its download rank improving from #21 to #3 from May ‘22 to Mar ‘23 in Germany and surging to #2 in France, behind Tinder, just 3 months after launch – and is among the top 3 most downloaded dating apps in 14 countries.

Hinge caters to those with serious relationship intent and demands more time of users upfront, so I doubt its user base will ever catch up to Tinder’s. But by virtue of drawing serious daters, Hinge should have more pricing power. I estimate Tinder’s US RPP to be ~$26, implying that Hinge, which does $27 from a user base heavily concentrated in rich Western countries, probably has a lot more room to grow (by comparison, The League, another dating app owned by Match Group, which admits members based on social status, educational attainment, and professional accomplishments, does more than $100).

Hinge’s unexpected success segues to another key point. While Tinder is by far its most significant banner, it is buttressed by a long tail of apps in Match’s portfolio, each catering to a different user base – snobs (The League), African Americans (BLK), Latinos (Chispa), Christians (Upward), single parents (Stir), serious daters (Hinge), gay men (Archer). Within the mainstream apps, there is even a plausible “lifecycle” narrative where users engage most on Tinder in their early-20s, then age into more “serious” apps like Hinge and Bumble in the late-20s and early-30s. Alongside those are apps targeting Asian markets (Pairs, Hakuna, Azar) and old school properties like match.com, Plenty Of Fish, and OkCupid that are being gracefully harvested for cash. Most of these properties will amount to nothing, but it’s hard to say which ones. Success in online dating business is hard to predict. Match spent $575mn on Plenty of Fish, which ultimately went nowhere, and $25mn for Hinge, which has become a top 3 dating app by revenue.

But thinking of Match Group as a portfolio of call options with random, binary outcomes is probably too simplistic. Despite chaos in the executive ranks, the company seems to have a knack for profitably growing brands. Match.com was for years the leading dating site in desktop. Tinder was incubated at IAC and grew to become the dominant dating app globally under Match’s ownership. Hinge did just $5mn in revenue the year it was acquired by Match and now, less than 5 years later, is run-rating at $400mn. Archer was built in-house and is close to rivaling Grinder’s US weekly downloads just months after its limited rollout.

A skeptic might retort that we don’t know the counterfactual, that Match is just riding the wave of colossal success that these banners would have experienced as standalone companies anyways. Fair! While there are some lesson and tactics shared across them, Match’s properties generally operate independent of one another (their flagship apps have different code bases and even different headquarters), which stokes the perennial concern that another app could launch out of left field today and steal Tinder’s users. But again, the highest-revenue generating dating apps in the US today (as far as I know) – Tinder, Hinge, Bumble, Grinder – were all founded more than 10 years ago, in the early days of smartphones. As long as mobile remains the dominant platform, it’s hard to see a startup introducing a novel angle of attack that siphons users away (AI girlfriends maybe?).

Given that dynamic, the natural exit strategy for a pre-revenue dating app that is starting to gain traction in some niche is to sell to Match. Even if you are of the opinion that Match isn’t operationally responsible for the success of its apps, they’ve at least put resources behind the right ones. Consider that, what, hundreds of US dating apps have launched since the mid-‘90s? Is it just coincidence, having nothing to do with resource allocation or execution, that 2 of the 4 highest monetizing ones in the US happen to be part of the ~45 that Match owns? Maybe, but I doubt it.

Match Group is for now a bet on Tinder. But as a vehicle of diverse apps catering to a broad swath of niches, managed by a group with a strong track record of acquiring and profitably nurturing the industry leaders, it is also a bet on the online dating category as a whole. I think you can feel good about the latter. In the Western world, the cultural taboos around online dating have more or less fallen away. By 2017, more heterosexual couples in the US met online than through any other channel, with a new S-curve for online dating forming at around the time smartphones took off.

In the Middle East and Asia, online dating is far more stigmatized (in Japan, for instance, Tinder users will commonly post pictures of flowers and landscapes instead of their faces) and monetizes at lower rates to boot. But even if adoption is never as widespread there as in the US, I suspect it will continue to trend the same way.

The number of dating app users globally grew by ~8% a year from 2015 to 2022 and I see no reason why growth should meaningfully slow.

Even in “mature” markets like North America and Europe, 57% of adult singles have yet to try a dating product.

In theory, Tinder also has room to grow, with only 24% of single 18-34 year-olds counting themselves active users. Another 35% are lapsed users and another 41% have never used Tinder at all.

All dating platforms must contend with success translating into users pairing off and leaving the platform. But this headwind is offset by new, larger cohorts of 18-year old’s who are going to be pulled to the most liquid network like the cohort before them, and lapsed users who reactivate their accounts when those relationships don’t work out.

In summary, Match Group is a vivarium of dating sites targeting a broad swath of interests and demographics. Its marquee brand, Tinder, is showing signs of user stagnation, but revenue growth has accelerated from 4% to 10% over the last 2 quarters on the back of significant price hikes and the introduction of weekly subscriptions, a rate of growth that it expects to maintain next year. Payer declines are moderating as users adjust to the changes, with management expecting a return to sequential growth by the middle of next year. Whether they can pull this off, let alone return to mid/high-single digit growth will depend on top-of-funnel growth, which they are trying to improve with product and marketing initiatives. I think they’re in a tough spot here for reasons I discussed. Hinge, meanwhile, is on fire. Last quarter they grew payers by 33% even as RPP advanced 8%. With just half the number of payers as Bumble and RPP at US Tinder levels, I suspect there is lots of runway for both metrics.

The msd revenue declines at Evergreen and Emerging (22% of revenue) should moderate somewhat as the segment continues to mix toward the fast growing Emerging concepts, which growing 40%-50% a year, partially offsetting the declines of legacy banners. Match Group Asia (9% of revenue) has reversed its y/y contraction and is now growing low-single digits as Azar, 2/3 of Hyperconnect’s revenue, is now growing 20%/year on the back of “AI-enabled” algorithmic matching (whatever that means), offsetting the continued weakness at Pairs (the largest dating app in Japan) and Hakuna. Meanwhile, operating margins have expanded from flat at the time of acquisition to around 10%. While Hyperconnect did not live up to Match’s metaverse ambitions and management would probably take back the acquisition if they could, it brought some advanced technology that can be leveraged across Match’s other brands and it doesn’t hurt to own a platform that is tuned to the cultural sensitivities of what could prove the largest addressable region for online dating.

Finally, last year Match paid $623mn to app stores, a huge sum compared to its $965mn of EBITDA. I wouldn’t buy shares on the expectation of massive fee relief, but maybe keep this option in your back pocket for a rainy day.

All things considered, I can appreciate how many think the stock looks attractive here at 18x trailing free cash flow, 14x EBITDA. To put things in perspective, Match has around the same market cap and only 25% more enterprise value than it did at the end of 2017, when Tinder was doing just 1/5 the revenue and Hinge wasn’t even part of its complex. At 40x free cash flow it was arguably overvalued back then but at less than half that multiple today I think you can make a reasonable case that the stock has overshot to the downside. Assuming 8% growth at Tinder (0% payer growth / 8% RPP growth), 27% at Hinge (18% / 7%) growth, 3% at Match Group Asia, 15% contraction at established brands, and 25% growth from emerging ones, blends out to ~9% revenue growth over the next 5 years. With so much of that growth fueled by pricing at Tinder, we could see a doubling of EBITDA that drops down to ~$4.5 in per share cash earnings (including stock comp). At 15x-20x + accumulated cash, the stock compounds between ~19% and 25%.

At the same time, that’s all just playing with numbers. I can’t say I’ve got strong opinions one way or another about the extent of Match’s pricing power, its ability to drive user growth, the efficacy of its marketing initiatives or pending product refreshes or really anything! Hinge is often pitched as a “hidden” asset that will become more appreciated as it makes up a larger part of Match, but I’m not sure how much long-term signal we can confidently glean from current results. Fade rates can be much steeper than investors appreciate. Tinder was growing by more than 40% just 4 short years ago, about as fast as Hinge is growing today. But then again, singles need to go somewhere to find dates and where else if not Tinder, Hinge, or any one of the dozens of apps in Match’s complex?

Disclosure: none of the accounts I manage own shares of Match Group

according to Sensor Tower data, as of 4q22 the male/female ratio was about 70/30 on Tinder and 60/40 on Hinge. According to Business of Apps, in 2021 the male/female ratio on Tinder was 75/24

Data is Beautiful

as of Jul ‘23, according to Statista

From the chart above you say, “ Even in “mature” markets like North America and Europe, 43% of adult singles have yet to try a dating product.” But it looks like the chart shows the percentage who have used a dating app. So, would the number you are referring to be 57%?